[7 blank pages]

LAW LYRICS

BY

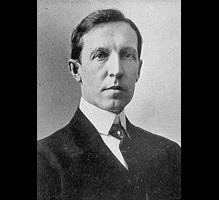

E. DOUGLAS ARMOUR, K.C.

TORONTO:

CANADA LAW BOOK COMPANY, LIMITED

1918

[unnumbered page]

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| To the Reader |

7 |

| Mr. Justice Shallow |

9 |

| Past and Present |

12 |

| The Student’s Dream |

16 |

| The Registrar’s Dream |

18 |

| The Squib |

20 |

| The Family Solicitor |

25 |

| The Six Carpenters |

27 |

| Ye Barristers of England |

29 |

| The Bull and the Scow |

31 |

| A Deed Without an Aim |

33 |

| An Original Writ |

35 |

| June |

37 |

| Communis Error Facit Jus |

38 |

| De Minimis Non Curat Lex |

38 |

| Nemo Est Hæres Viventis |

39 |

| [unnumbered page] |

[blank page]

DEDICATION

It’s a curious observation

To make, that dedication

Is common both to highways and to books;

But I’m satisfied that you

Must acknowledge that it’s true,

No matter how ridiculous it looks.

But a highway’s always free,

While a book can never be,

(The publishers, of course, would not advise it),

And so I beg to state

That I gladly dedicate

This little book to any one who buys it. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

TO THE READER

Some men write for fame; And others write for lucre, As they would play a game Of billiards, bridge or euchre. Some write “random verses” And publish them to try them; And sadly view their purses When people will not buy them. Some men say they write Because “the spirit moved them,” But if the sprite had sight He well might have reproved them. “The fruit of idle hours” Is another one’s excuse, Suggesting latent powers That might be put to use. You ask me where I place Myself in offering thee these Versicles, a case Of scribendi cacoethes? Rejecting all suggestion That I would write for pelf, I cannot solve the question, For I don’t know myself. And so of thee I ask it To find for me a niche, Or a waste-paper basket— It doesn’t matter which. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

MR. JUSTICE SHALLOW

Mr. Justice Shallow was very tall and thin; His nose was long and aquiline, and nearly reached his chin; His hair was rather absent, and his face was shaven clean, And his general appearance was particularly keen. His cheeks were very sunken; and his eyes were very bright, And, aided by his lantern jaws, would scintillate with light, As he listened to the Counsel chopping logic in his Court, Antiphonally striving each his client to support. He made his reputation at the Bar by charging fees Which embarrassed all his clients, and by splitting hairs with ease; Then he was made a Justice by a parsimonious nation, At a salary which nearly kept him from starvation. As a judge, his striking talents and his wit so brightly shone That nothing like it ever was, or ever will be, known. His skill and patient industry were both beyond compare, And the memories he has left us are exceeding rich and rare. For him there never did exist a patent ambiguity— He’d prove it one or other with the greatest perspicuity; And distinguish, in a manner, too, that left it free from doubt, ’Twixt a possibil’ty coupled with an interest, and without. He’d demonstrate, so cleverly that anyone could see, The proper way to limit a determinable fee;* E converso, then, by reasoning which no one could resist, That such a limitation never did, or could, exist.**

*“This limitation to R. of a determinable fee simple appears to me to be free from objection in every respect, notwithstanding what may be said in any book as to the effect of the Statute of Quia Emptores upon the creation of estates in fee simple, determinable or qualified.”Per Joyce, J., in Re Leach (1912) 2 Ch. at p. 427.

**“In fact, there is not any authority to be found for any such determinable fee. I have looked at an enormous number of cases to see if I could find such an authority, but I have been quite as unsuccessful as the Counsel for the plaintiff, and I think no such case can be found.” Per Jessel, M.R., in Collins v. Walters, L.R. 17 Eq. at p. 261. [page 9]

But that was for which his worshippers all held him most in awe Was his triumph in the field of logic, rather than of law; For ’twas he who made it possible for other men to see The real, basic difference between tweedle-dum and -dee. And yet, he did not rest upon his fame as a logician; His learning was accorded universal recognition; ’Twas varied, deep, profound, profuse and painfully exact, And applied, in writing judgements, with inimitable tact. It’s said that, when he was a child, he would be found at times Perusing Coke on Littleton instead of nursery rhymes. And, when he was still quite a youth, he set himself to learn The truth about remainders from the work of Mr. Fearne. It’s idle to attempt to tell of all he read and did; He mastered Sheppard’s Touchstone, Preston, Sanders, Coke and Tidd; And, straining every nerve to learn, he gave himself no quarter, Absorbing legal knowledge like a sponge absorbing water. He reasoned out his judgements with a wonderful acumen Defying explanation, unless he were superhuman. He’d split and subdivide the very finest points of law, And none were ever able to detect a single flaw. In the end, his gentle nature and emaciated frame Could not withstand the fierceness of his intellectual flame; And his friends and his admirers saw him slowly waste away; Then they laid his bones to rest—for there was nothing else to lay. And then they turned to mourn, and wonder whether any other Would ever rise to equal their lamented, learned brother— To perform the last saw duty they could do on his behalf, By writing, for his tombstone, this solemn epitaph:— [page 10]

THE REMAINS

OF

JUSTICE SHALLOW

LIE BENEATH THIS SACRED STONE.

IN LIFE HE WAS AN UPRIGHT MAN,

THOUGH NOW HE’S LYING PRONE.

HIS TERM OF YEARS ON EARTH WAS MARKED BY PATIENT ASSIDUITY.

WE TRUST HE’S NOW REVERSIONERIN BLISSFUL PERPETUITY.

If these lines are ever read by anyone who’s able to recall No vivid recollections of this man—or none at all— It may relieve his mind to learn, and to conclude therewith, That Mr. Justice Shallow was—nothing but a myth. [page 11]

PAST AND PRESENT

When John Doe and Richard Roe, And people of that ilk, Stravagued about the Courts of Law With gentlemen in silk; When lawyers plied their subtle minds To show the reason why A writ should not be in the per, But in the per and cui; Then pleading was a real art, And built up reputations, And characters were won and lost In drawing replications. The plaintiff’s simple, homely plaint Took various shapes and courses, And, driven about by subtle pleas, Got tangled in the process; Until, at last, the issues were Impossible to sunder, Like nothing else upon the earth, Or in the waters under. Demurrers, too, and special pleas Embarrassed and delayed it; And perhaps the venue never should Have been where he had laid it. The spirit of the law was rendered Subject to the letter; The point was whether pleas were good, Or other pleadings better. The disappointed suitor oft Was paralyzed with terror, When told the place to right his wrong Was in a Court of Error. [page 12] What wonder, then, that in the days Which we have left behind, Justice was represented as A woman who was blind! Then, too, scintilla juris shed Its tiny, sparkling ray, As it served the nimble uses, springing, Shifting on their way. The owner ousted from his land, Quite regularly came Just once a year, without his gate, And made continual claim. But, if disseisor’s death occurred While he did wrongly hold, His heir, by law, was owner, and The right of entry tolled. The vagrant’s death thus put the owner In a different plight; His right of entry barred, resort Was had to writ of right. And many more astounding things Might shock you if I told them; At any rate, I shall not try— There isn’t space to hold them. In modern practise pleading isn’t Either art or science; And even rules of practise don’t Require strict compliance The plaintiff says a thing is so; Defendant then denies it; The Judge hears any thing that’s said— And that’s the way he tries it. [page 13] And Counsel’s opening address The Judge can do without, He merely says—”Well, gentlemen, What is it all about? First witness, Mr. A. —How long D’youthink the case will run? And Mr. B. can tell me his Defence when you are done.” Attempts to rule out evidence, Or ask for its rejection, Are met with— “I’ll admit it now, But subject to objection.” The form and letter of the law Give way to its intendment, And any error made is now Corrected by amendment. Scintilla juris now yields to Original momentum; And uses spring and shift, because There’s nothing to prevent ’em. For friends were made and friendships lost In arguing about it; Until, at last, a statute said That we must do without it. The trespasser can rest in the Possession of his plunder, Unless a writ is issued in Ten years—or something under. To John Doe and Richard Roe We long since bade farewell; They had their work to do, and after All they did it well. [page 14] Of all the ancient learning thus Of which we’ve been bereft, The Rule in Shelley’s case is now The only one that’s left. And many other things my pen Might tell if I applied it; But then, one never knows what’s what Until the Court has tried it. [page 15]

THE STUDENT’S DREAM

I sat alone, with Benjamin on Sales upon my knee; The letters dance before me and the words I couldn’t see; I’d attended many a lecture, and had taken many a note, But I couldn’t see a grain of sense in anything I wrote. I was reading for my Call exam., immerses in deepest gloom, Oppressed with nervous doubt and dread of what might be my doom; I was overcharged with Equity, and Common Law and Torts, And altogether I was feeling greatly out of sorts. The books were piled around me in a litter on the floor; There were Marsh’s “Court of Chancery,” and perhaps a dozen more, A wretched book on Titles, and another one on Wills, De Colyar, Pollock, Leake and Best, and poor old Byles on Bills. And now a mist seemed gathering about me in the room, And through it all the books in curious forms began to loom; They perched in turn upon my knee, and flapped their leaves and fluttered, And whirled in circles round my head, and ominously muttered. They pulled my hair and boxed my ears and bumped against my nose, And then they settled on the floor in front of me in rows. And Blackstone hobbled forward with a question to propound— “What is the rule in Shelley’s case, and where can it be found?” This seemed to be the signal for the ill-conditioned rabble, For they poured forth questions right and left as fast as they could gabble. “Does dower attach on land alone? If so, pray answer how A man can say, ‘with all my wordly goods I thee endow’?” [page 16] “State reasons for all answers, and especially the next, And where the lectures differ from your reading of the text.” “If A. kick B., and B. kick C., who, driven by distraction, In turn kicks A., is this what’s called circuity of action?” “If A. sues C. for damages, can C., if he’s a mind Buy up the kick B. got from A. and pay A. off in kind? Or, if it’s not the assignable, can C. set up the plea That, though he gave the kick to A., ’twas to the use of B.?” “If either course you should adopt, will counter-claiming do, Or does the law of set-off apply to a set-to? In case you should not think so, but advise that C. sue A., Explain, as nearly as you can, what you would make C. pray?” “Suppose your neighbour dines with you and guzzles too much port, Are you, as neighbour, bound to give him lateral support?” “If B. sues A., for that A. merely shook his fist at B., Is falsa demonstratio non nocet a good plea?” “How is it that the ancient forms of writ did not out-live us? For instance, writ of entry sur disseisin in the quibus?” “Is a double possibility your chance of getting through?” “And, can you sue in trover for conversion of a Jew?” “If attendance at the lectures is considered, as a rule, To be equally important for the students and the school, Then why should not the Benchers make arrangements to have cabs sent For those who are habitually late, or who are absent?” At last, I got so angry at this senseless sort of joke That I aimed a kick—and nearly tumbled off my chair—and woke. The fire was out, the lamp was low, and I was cold and weary; The room seemed full of calf-bound ghosts that made me feel quite eerie. I let the books lie where they were and stumbled off to bed, But, before I pressed the pillow with my throbbing, aching head, I consulted a decanter which I keep upon my table, With “sumendumbis in die atque noctu” on the label. [page 17]

THE REGISTRAR’S DREAM

The Judge came into Court in state Arrayed in gown and bands; He bore himself with mien sedate, And gently rubbed his hands. At once the Counsel all arose, And all “Good morning” said; The learned Judge first blew his nose, And then inclined his head. The Registrar, already there, Bowed with accustomed grace, And then subsided in his chair And called the opening case. And then he took a well-earned rest, His face with radiance beaming; His chin sank slowly on his breast, And then he fell to dreaming. He dreamed he was a pundit, ripe To rule in Law’s abode, Instead of just a conduit-pipe Through which the judgements flowed. Subconsciously his memory roved O’er Judgements and Decrees, The Precedents and Forms he loved As Counsel love their fees. And soothed to rest with thoughts like these He soft and gently breathed, And, half recumbent at his ease, His face in smiles was wreathed. Then names of various writs revolved Round his half-open ear, And Prohibition got involved With two per centum beer. [page 18] And putting two and two together, He slowly pondered o’er What was the proper answer—whether Twenty-two, or four. His puzzles brain began to shew Its influence in his face; To tightened lips and knitted brow The wreathed smiles gave place. Then suddenly his breath he caught With pain, and almost cried At the grotesque but gruesome thought That feme sole should be friend. And through his brain the questions flew In still increasing numbers, Until, at last, he plainly grew Uneasy in his slumbers. Then all at once the Counsel rose And cut the strangest capers; They danced upon their heels and toes, And flung about their papers. They plucked their gowns above their thighs Their dignity forgetting And at each other winked their eyes While gaily pirouetting. And on they went, by leap and bound, And threaded in and out, And then they whirled around and round— It was a glorious rout! But all the fast and furious fun Was ended at a stroke, All solemnly the clock struck ONE! The Registrar awoke. He opened wide his sleepy eyes, His cheeks were red and burning; He gazed around him with surprise And found the Court adjourning. [page 19]

THE SQUIB

Once on a time, when we knew what we knew, The story was always accepted as true, That a certain old monk, in his moments of leisure, Instead of directing his efforts of pleasure, Was messing about making mixtures of chemicals, More deadly and dangerous than his polemicals, In a cell underground, a secluded and dark hole, Until he got sulphur, saltpetre and charcoal Made in a powder that every one knows of— And thus was invented the first great explosive. But now we don’t really know what we know, But just for the moment assume that it’s so. That a monk should engage in such works of destruction, Instead of imparting religious instruction, Is denied by some people who make the contention That the tale not the powder’s the real invention. But there’s no reason why a monk shouldn’t try To invent any mortal thing under the sky— And this gentle monk might indeed with propriety Have won from S. PETRE both powder and piety. That’s but the beginning of things, not the end, For after events in their natural trend Brought the bomb, the grenade and the mischievous squib Which mischievous people can purchase ad lib. And a squib, as we read in careful report,* Had the honor of splitting a most learned Court. Young Shepherd one morning on mischief was bent, And, without any malice or evil intent, He lighted a squib and tossing it high Threw it into the market house standing near by; And there, as it were pre-ordained by the fates, It fell with a whizz on the standing of Yates, A man who sold gingerbread, perhaps having gilt on it, And didn’t want dangerous substances spilt on it.

*Scott v. Shepherd, 2 W. Bl. 892. [page 20]

One Willis was guarding the wares in the stall, And, not liking its dangerous presence at all, He advanced it a stage, as they say in debates, In order to save the belongings of Yates. So in curve parabolic the squib diabolic Soared on through the air on its mischievous frolic, Still fizzing and whizzing and viciously spitting, And fell on a stall in which Ryal was sitting. Then Ryal, without making any pretence Except that he acted in pure self-defence, Threw it on to continue to riotous flight, Not caring a button where it might alight. By this time the squib couldn’t hold itself in; It exploded in fact with a thundering din In the face of young Scott, who was standing near by, And the damage it did was to put out his eye. So, the course of the mischievous squib having run, The course of the lawyers was forthwith begun. Young Scott then at once heavy damages sought, And an action of trespass ’gainst Shepherd was brought. In due course of time the case came on for trial, And of course there could possibly be no denial Of the fact of the injury done to Scott’s eye, And that by a burning squib caught on the fly, No doubt but that Shepherd had started the thing, Nor that Willis had given the missile a fling, Nor of the fresh impetus given by Ryal— Of all these of course there could be no denial. Shepherd’s act, said the jury, ’s the proximate cause Or the causa causans in the phrase of our laws; And they fixed the amount Mr. Shepherd should pay At one hundred pounds for his frolic that day. Now Counsel for Shepherd no courage did lack, And he mustered reserved for a counter attack. When the Court met in Term in imposing array, Nares, Blackstone and Gould and Chief Justice De Grey, There’s no doubt that he made a most palpable hit When he rested his case on the form of the writ, Which claimed damage for trespass, and not on the case, A point to which everything else must give place. [page 21] If Shepherd had flung the thing straight at Scott’s eye, It is clear that an action of trespass would lie; But the action of Willis and Ryal deflected The course into which the squib first was projected; And therefore the injury wasn’t direct, And an action of trespass was quite incorrect. Then the judges took time to advise and consult, And the judgements which follow will shew the result. But first, for a moment, consider the case— Here is Scott with one eye and a disfigured face, All occasioned by Shepherd’s most mischievous act, Although it was done without malice in fact. All agreed he must pay for the injury done, Althought he conceived it in mischief or fun. And now it would seem to be sound common sense That Scott should no longer be kept in suspense; Yet the Court thought they couldn’t bring Shepherd to task for it If Scott by his writ didn’t properly ask for it. So they ransacked authorities looking for light Upon whether the form of the action was right. And Nares (Gould agreeing) delivered his views, And he was of opinion they couldn’t refuse To give the relief in the way it was sought, For he thought that the action was properly brought. A mischievous faculty Shepherd imparted To the squib when he lit it and when it was started. In the whole of its flight then the squib never lost it, From the moment that Shepherd first lighted and tossed it; And anything Willis or Ryal had done Didn’t add to the mischief already begun; They furthered his act, and his agents must be, And Qui facit per alium facit per se. But Blackstone dissented, and was for defendant; For clearly Scott’s action could not be dependent On Shepherd’s just doing an unlawful thing, When he gave to the squib its original fling; [page 22] But on whether the damage was clearly immediate, A point upon which all his brothers agreed, yet They differed from him on the question of fact Whether all flowed directly from Shepherd’s sole act. It is true that a squib has the power for ill; But so has a stone which was thrown and lies still. But, if other men set it again on the fly, It is clear that no action of trespass will lie Against him who at first launched the stone into space; But against him who gave it its ultimate place. Just so with the squib, for it’s easy to see That Willis and Ryal were perfectly free To extinguish the thing, or to throw it away; But then if they threw it he felt bound to say That they must be careful to see where it lit, Or else they should answer for whom it might hit. So the action for injury done to Scott’s face, Which was quite indirect, should have been on the case. The last one to which I refer, as I must, is That of De Grey who was then the Chief Justice. He agreed with the principles Blackstone expressed; But with their application he wasn’t impressed. (Just so the wise Bunsby, in giving advice To his friend Captain Cuttle, in language concise Explained that the bearings of his observation Depended entirely on its application.) A general mischief at first was intended, And in a particular mischief it ended; And if general mischief was meant at the start of it, The particular mischief was certainly part of it. (If a man went a-fishing and cast out his line, No one would attribute to him the design Of trying to catch a particular fish, For any that came would accord with his wish; And if ’twere a big one he happened to kill, What man in his place wouldn’t vaunt his own skill! I don’t mean to say that Chief Justice De Grey, In his judgement, at all brought a fish into play. But the judgement of any judge, sooner or later, Is sure to attract some obscure commentator. So, if you observe what I say, you’ll see then this is Merely an Editor’s note in parenthesis.) [page 23] So the battle of wits was concluded at last, And Scott held his verdict for damages fast, With the glorious vision displayed at finality Of Justice triumphant in spite of formality. In the present enlightened, reformative age Such a battle as this no one ever could wage; All formal objections are in ill-repute, And justice is done on the point in dispute; Or, to use other words, it may thus be expressed— You just prove the facts, and the Court does the rest. [page 24]

THE FAMILY SOLICITOR

Oh! woe betide!

My father died,

And, by a paper styled

His testament,

The best he meant

To do for me his child.

For, as I read

The Will, it said

His land was mind to hold;

But (was it just?)

It never must

Be mortgaged, leased or sold.

Oh! woe is me!

I went to see

The family solicitor;

I knew him well

And, truth to tell,

I trusted him simpliciter.

My friend, said he,

A gift in fee

Can not be thus restricted.

He pointed out

How, without doubt,

The gift and terms conflicted.

A case was then

Prepared, and when

In time I learned its fate,

The Will was good

Just as it stood—*

Costs out of the estate.

*It may not be out of place to recall that the Ontario cases hold that a partial restraint on alienation is valid. [page 25]

But this rebuff Was not enough To make my lawyer feel At all distressed, Because he pressed Me strongly to appeal. I trusted him, But just a dim Suspicion crossed my mind, That it was better That the fetter My estate should bind. So I replied, I’m satisfied That you have done your best, But I’m afraid The case had made A quite sufficient test. Then here’s the Will, And there’s my bill; I’ll take your note of hand; Or, I’ll concur If you prefer, A mortgage on your land. The estate must pay The costs, I say, For so the Court has stated; So will you now Advise me how? For I can’t alienate it. Oh! woe is me! For now you see I’m not a welcome visitor When, it may be, I go to see The family solicitor. [page 26]

THE SIX CARPENTERS

It fell to the six men of the plane and the saw To develop a very nice point in the law, Viz., whether by failing to settle their score In a tavern, they trespassed on entering the door. If the technical phrase for such trespass you wish you Will find it is called in the books ab initio. These six jolly carpenters one day combined To enjoy themselves drinking, and set out to find A suitable place for their space, and it’s said That the place they selected was called The Queen’s Head. If they really wanted to raise any rumpuses There were other such places, e.g., Goat and Compasses, Where intimate dealings with wine-butts might end In each of them (like a goat) butting his friend; Or, The Cat and the Fiddle—with “Hi!diddle, diddle! Hi! Jolly landlord, come read us a riddle― The glasses are empty for each one has hid all His share of the win his corporate middle; While the landlord replies with a sorrowful “How?” But facts will be facts, and no more can be said, For the fact is a fact that they chose The Queen’s Head. Then the six jolly carpenters ordered a quart, It might be of sherry, it might be of port, But, at any rate, wine, which they paid for like men, But, not being satisfied, ordered again A quart of the wine and a small piece of bread; And their stubborn refusal to pay for it led To a suit against all of these amiable gentry For trespass based on their original entry. What reason they had for refusing to pay The report doesn’t state, but I venture to say That if one had been called for it might have been shewn That the wine from The Queen’s Head got into their own. [page 27] And the following points were resolved by the Court, As shewn in Sir Edward Coke’s learned report:—* If by law one should enter a house, he may use it Within legal limits, but mustn’t abuse it. For it, when he’s there, he should pilfer or loot, It’s abundantly clear that the law will impute An evil intent on his first having gone there, By reason of what he had afterwards done there. But if, having entered by leave of the owner, He converts to his use, say, an old marrow bone or A cup or a saucer, a table or chair, Or something to drink, or something to wear, His entry will still remain lawful in fact, Yet he may be sued for his subsequent act. Now the six jolly carpenters entered by licence, And though they were never imbued with the high sense Of duty which would have compelled them to pay For the ultimate drinks that they ordered that day, Yet they lawfully entered, and lawfully stayed, And the fact that the price of the wine wasn’t paid Would not be sufficient in law to transmute These innocent acts into cause for a suit. Besides which, a trespass imports a wrong doing, And merely not doing is no cause for suing. But this is now chiefly historic, because Of the changes in fashions as well as the laws; For taverns recede as ideas and advance, And soon they will just furnish food for romance. They are fast giving way to palatial Hotels, And, I daresay in time, Hydropathics and Wells. And a wave of intemperance has over us burst, Sending ale, wine et. al., to the realms of the curst; So there’s no use in any one raising a thirst To be treated with two per cent. beer at its worst. And schemes for providing for man’s entertainment, In order to reach a successful attainment, (Like Moses, when found by King Pharoh’s young daughter, Or Noah’s Ark) have to be floated on water.

*8 Rep. 146 a. [page 28]

YE BARRISTERS OF ENGLAND

Ye Barristers of England

Who guard our hearths and homes,

Whose learning is entombed within

A thousand musty tomes;

Your ponderous briefs unfold again,

Now that vacation’s o’er,

And rant,

Yes, and cant,

While the jury loudly snore,

While you argue cases loud and long,

And the jury loudly snore.

The cases of your fathers

Start up on every side;

The Bench—it was their field of fame,

And precedent their guide;

Where Coke and mighty Blackstone sat,

You, perhaps, may sit some day,

If you rant,

Yes, and cant,

While the jury snore away;

If you argue cases loud and long,

While the jury snore away.

Brittannia needs no bulwark

While she her Bar supports;

Her pride is in the Courts.

The thunders of her mighty Bar

Resound from shore to shore,

As they roar

Evermore,

While the jury loudly snore;

As they argue cases loud and long,

And the jury loudly snore. [page 29]

The Parliament of England

May yet, terrific, turn,

And put an end to bills of costs

And all your law-books burn.

Then, then, ye zealous Barristers,

Your words shall cease to flow,

And your name

Lose its fame,

As the jury homeward go,

And your fiery words be heard no more,

As the jury homeward go. [page 30]

THE BULL AND THE SCOW

The skipper never dreamed of harm,

As he moored his scow ’longside a farm

Upon the river.

He made all fast with a rope of hay,

To keep the craft from floating away

A-down the river.

A bull it was, and not a cow,

That strayed from the bank upon the scow

Upon the river.

He first looked this, and then that, way,

And then he looked at the rope of hay,

Gurgled the river!

He looked, he smelled, and then he ate,

And the scow sailed off with its precious freight

A-down the river.

The farmer’s remarks were not polite,

As he chased the scow with all his might

Along the river.

And the skipper’s speech was quite profane.

As he followed the farmer with might and main

Along the river.

But the scow sailed on till struck with a thud,

And pitched the bull, who was chewing his cud,

Into the river.

So the scow was wrecked, and the bull was drown’d,

And the Crowner’s Quest a verdict found

Against the river. [page 31]

Then the farmer swore that he’d had full

Damages paid for the loss of his bull

Drown’d in the river.

And the skipper swore that the farmer should pay

For the loss of the scow by the eating of the hay

Upon the river.

So, in the heat of their agitation,

They plunged headlong into litigation

As long’s the river.

And now they’ve learned that, whoever was wrong,

They can never get their differences settled, as long

As runs the river. [page 32]

A DEED WITHOUT AN AIM

Know all men by these presents, and do ye remember— The Indenture made (say on some day in December) One thousand eight hundred and seventy (dash) (Better not let the date and delivery clash), Between John Smith of (blank) in the Country of (blank) (Setting forth where he lives and his calling or rank), And Susan his wife, of her free will and power, Who joins for the purpose of barring her dower, He of the first part, of the second part she, And lastly John Brown of the third part, Grantee, Doth witness that, for and in consideration Of (the sum here insert), lawful coin of our nation, Which he hereby acknowledges he doth receive As an adequate price for his land, you perceive, John Smother of the first part, as mentioned before, Doth grant, convey, transfer, assign and set o’er All and singular those certain parcels or tracts Of land (here describe them according to facts) To John Brown aforesaid his heirs and assigns, With their easements, ways, waters, their woods and their mines, Their profits, appurtenances and their rents, And in fact all that’s meant by hæreditaments, Habendum, Tenendum, which means as you see, To have and to hold unto Brown the grantee, To his use and behoof, and to that of none others, His heirs and assigns and his sisters and brothers, His aunts and his uncles and also his cousins, And children, although he may have them by dozens. And Smith of the first part, the covenantor, Whose name you observe has been mentioned before, Doth covenant, promise and also agree With John Brown aforesaid, the covenantee, That he hath the right to convey the said land, Notwithstanding aught done by him touching it, and The said Smith and his heirs also make this concession That Brown and his heirs shall have quiet possession Of all that the herein before described land, And that free and clear of all claim and demand, [page 33] Gift, grant, bargain, sale, jointure, dower and rent Entail, statute, trust, execution, extent, Done, suffered, permitted or otherwise made By Smith or his heirs on the land now conveyed. And that Brown’s estate may have the better endurance, Smith also agrees that such further assurance As Brown or his heirs may in reason request, And in Counsel’s opinion may seem to be best, He will execute, so that there may be no flaw To subject Brown aforesaid to process of law; Nor hath he done aught whose effect e’er might be To incumber said lands in the slightest degree. That his right to the said lands may certainly cease, Smith doth, by these presents, remise and release All his interest, title, estate, right and claim Of, in, to, from, out of and touching the same, Unto him of the third part, videlicet Brown, And those claiming under him all the way down. And Susan, in case she should outlive her spouse, And should thereupon claim what the law her allows, Doth hereby release all her claim and demand Right and title to dower in or to the said land. In witness whereof all the parties aforesaid Have hereto set their hands and their seals—and no more said. [page 34]

AN ORIGINAL WRIT*

To John Smith

His servants and agents, Victoria

Sends Greeting. We trust that this process won’t bore you.

Whereas one John Brown now lately hath filed

A bill of complaint here, wherein are compiled

An account of your doings, and saith he is grieved

Thereat; and he asks that he may be relieved

As against the aforementioned acts of iniquity,

Because they’re repugnant to conscience and equity;

Now as it is shewn that the truth is the same as is

Fully related by him in the premises,

We’ve caused this to issue upon due inquiry

Secundum discretionem boni viri.

And if you should ask us, Vir bonus est quis?

Of our grace and mere motion we answer you this,

(To which we may add, you by no means deserve it):—

Qui partum consulta qui juraque servat.

Considering therefore that Brown hath related

The truth touching what in his bill he hath stated,

We strictly enjoin upon to refrain

From the acts we referred to before, under pain

Of incurring our heavy displeasure; and not

Only that, but we’ll make it exceedingly hot

For you the aforesaid iniquitous Smith;

For we’ll order our Sheriff to take you forthwith,

To conduct you to where we give plain lodging gratis

And watch you with care till you cry out jam satis;

There we’ll cause you to live like a very recluse,

While we meanwhile appropriate to our own use

Your lands that you bought with your hardly earned pelf,

Your carriages, horses, blue china and delf,

Your ormolu clocks, your champagne and hocks,

Your plate that you keep under two or three locks,

And your profits from money invested in stocks,

Your carpets, and Zooks! your piano and books,

*Written at a time when writs of injunction were in use, threatening dire penalties for infraction thereof. [page35]

Your pictures suspended from silver gilt hooks, Your statuettes standing in nice little nooks, And your mirrors in which your wife constantly looks; Your treasures of art that are dear to your heart, With which you declare that you never will part; And we’ll do everything we can think of that shocks you While Brown looks on, coolly, and laughs at and mocks you. And when we’ve disposed of your jewels and trinkets, We’ve no hesitation in saying you’ll think it’s As well to obey our decrees and commands, And thus save your goods and your chattels and lands. Now, to shew you that this is not all empty brag― As witness out Chancellor Godfrey de Spragge,* Who measures the rights of each case it’s put By the breadth of his soul and the length of his foot. Now glance at the margin―pray look at the seal, And the stamp duly cancelled―more proof that you’ll feel Our Vengeance, worked out without any compunction, If you do not choose to obey this injunction.

*The Hon. John Godfrey Spragge was Chancellor of Ontario when this was written. [page 36]

JUNE

Justices are sitting In the month of June, And the long vacation Can’t arrive too soon. Time is dull and heavy, Does not seem to flit; Till the long vacation Justices must sit. The dreary, drowsy dronings Arising from the Bar Can hardly pass for arguments, Whatever else they are. And the judgments dropping Slowly from the Bench Give one side an ecstasy― T’other one a wrench. But the law you’re getting When the weather’s hot Is sometimes quite refreshing― But sometimes it is not. Oh! but time is heavy In the month of June, And the long vacation Can’t arrive too soon. [page 37]

COMMUNIS ERROR FACIT JUS

When learned of Judges chance to err, And find too late they’ve gone astray, What remedy can they confer? How can they wash the stain away? They coin a phrase to gloss it over, And solemnly express it thus, We’ve gone so far we can’t recover, Communis Error facit jus.

DE MINIMIS NON CURAT LEX

It’s true the law is comprehensive, It’s jurisdiction most extensive; For every wrong beneath the sun The injured can have justice done; But―do not stop to reason why, Be warned in time, and do not try With trifling things the Court to vex, De minimis non curat lex. [page 38]

NEMO EST HÆRES VIVENTIS

The sense of the maxim’s apparent, For, no matter how you contrive, No person is heir to his parent As long as his parent’s alive. But he who was but heir apparent Upon his late parent’s decease, At once becomes heir to his parent, For the rule and its reason then cease.

OR

Nemo est hæres viventis― By this maxim what’s really meant is, When a man is alive By no means you contrive Can you prophesy what the descent is. [page 39]

[7 blank pages]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.