[7 blank pages]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration]

[blank page]

[illustration]

BROCKVILLE

Looking west on the St. Lawrence

TORONTO

HENRY ROWSELL.

KING STREET

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

THE MAPLE-LEAF,

OR

Canadian Annual;

A LITERARY SOUVENIR

FOR

1849.

There’s a language of flow’rs, understood full well, But the message of joy or grief; But the heart’s hidden thoughts is there one can tell, When the gift’s but a simple Leaf?

TORONTO:

HENRY ROWSELL.

KING STREET.

[unnumbered page]

CONTENTS.

- PREFACE.

- THE LAY OF THE EMBLEMS.

- HAMILTON.

- EDITH.

- “THE SEA! THE SEA!”

- RICE LAKE BY MOON-LIGHT.

- “COME TO THE WOODS.”

- GIBRALTAR.

- CHANGES OF AN HOUR ON LAKE ERIE.

- ROUGH SKETCH BY A BACKWOODSMAN.

- THE TWO FOSCARI.

- THE BANK OF IRELAND.

- MARIA.

- TRANSLATION FROM HORACE CARM. II. 19.

- SONG OF THE ANGLO-CANADIAN.

- A FAREWELL.

- A CHAPTER ON CHOPPING.

- THE MINSTREL’S LAMENT.

- THE FUNERAL OF NAPOLEON.

- TRANSLATION FROM HORACE, CARM. II. 14.

- TWO SCENES.

- A STORY OF BETHLEHEM.

- MORNING PRAYER.

- ONTARIO, A FRAGMENT.

- LADY MAY.

- THE BULL-FIGHT.

- SERENADE.

- CORIOLANUS.

- THE FREED STREAM.

- A CANADIAN ECLOGUE.

- BROCKVILLE. [unnumbered page]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

- FRONTISPIECE—HAMILTON.

- VIGNETTE—BROCKVILLE.

- DENDURN.

- EDITH.

- GIBRALTAR.

- THE TWO FOSCARI.

- THE BANK OF IRELAND.

- MARIA.

- THE FUNERAL OF NAPOLEON.

- BETHLEHEM.

- MORNING PRAYER.

- THE BULL-FIGHT.

- CORIOLANUS.

- COURT-HOUSE AT BROCKVILLE. [unnumbered page]

SINCE we last took leave of the readers of “THE MAPLE LEAF,” twelve months have rolled away. During that period, how many stirring—how many touching events have taken place! What changes, both public and private! Assuredly, stern has been the teaching, and solemn the lessons, of the year which is now drawing to a close. The retrospect presents a spectacle, such as the present generation have never before beheld: kingdoms prostrated, or shaken to their centre—empires rocking to their fall, or heaving with unwonted agitation—social systems, the growth of centuries, overthrown—ancient constitutions levelled—all Europe so convulsed by the social earthquake, whose shocks have not yet ceased, that nations beyond the sphere of its present influence tremble, lest ultimately they too should be involved in the wide-spreading uin; and amidst this scene of wild confusion, our own glorious Parent-State, unshaken, undismayed—the refuge of misery, the haven of peace, the home of Liberty. Well may we rejoice in British connexion—well may we be proud of being united by filial bonds—

“To her upon whose ancient hills bright Freedom dwelleth yet— Whose star of empire ruleth still—whose sun hath never set; The shadows of a thousand years have flitted o’er her brow, And the sunlight of the morning bathes her cloudless beauty now.”

And ah! what sad changes by our own firesides does the eye of mournful memory observe, as it glances back to our last “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year”! Fond hopes crushed—bright prospects darkened—“the household gods shivered on the hearth”—sweet ties, which years had twined all the closer, in an instant and forever torn asunder—

“The eyes that show Now dimm’d and gone— The cherished hearts now broken!

But we must not allow the sombreness of our own pensive thought to cast a shade upon the feelings appropriate to this joyous season. The [unnumbered page] gloom of the cypress-bough, but ill consorts with the bright tints of “the Maple-Leaf.” Our little volume is the Souvenir of joy, not of sorrow; and its pages, like the dial, were intended to register

“Not darkness, shade or show’r, But each bright sunny hour.”

Our brief but pleasing duty, then, (for we turn our steps from the path in which we have strayed,) is, to express our sense of the favour with which our humble contribution to Colonial literature has been received, both here and “at home”; and to present our Publisher’s acknowledgment of the success which has hitherto attended his undertaking.

Adhering to the intention which we last year expressed, we have endeavoured to preserve the distinctive characteristics of a “Canadian Annual,” and at the same time render its contents interesting to those around us, who might reasonably expect that we should not limit ourselves to well-known and familiar subjects.

One word to our correspondents, and we have done. At our commencement, we formed two resolutions regarding the literary contents of “THE MAPLE-LEAF,” from neither of which have we, so far, in any instance departed—that they should be supplied “by none but those who were the children of Canada, either by birth or by adoption”; and that nothing should appear in our pages, which had previously been published elsewhere. Of the propriety of adhering to the latter of these, we have more than once been tempted to abandon our determination. We are, however, still inclined to cull only from the growth of our own soil; and although fully sensible of the additional lustre and fragrance which the contributions of our kind friends on the other side of the Atlantic would give to our volume, we prefer the native graces of the simple offering gathered in our woods:

“The flow’rs we bring are wild, ‘tis true—

Their perfume faint, and pale their hue;

But they spring round our homes in ‘the Forest-land,’

And they’re twin’d, all fresh, by our children’s hand.”

KING’S COLLEGE, TORONTO,

December 5, 1848. [unnumbered page]

The Lay of the Emblems.

Oh! beauty glows in the island-Rose, The fair sweet English flow’r— And Memory weaves in her emblem-leaves Proud legends of Fame and Power! The Thistle nods forth from the hills of the north, O’er Scotia free and fair— And hearts warm and true and bonnets blue, And Prowess and Faith are there! Green Erin’s doll loves the Shamrock well! As it springs to the March sun’s smile— “Love—Valor—Wit” ever blend in it, Bright type of our own dear Isle! But the fair forest-land where our free hearts stand— Tho her annals be rough and brief— O’er her fresh wild woods and her thousand floods Rears for emblem “The Maple Leaf.” Then hurrah for the Leaf—the Maple Leaf! Up, Foresters! heart and hand; High in heaven’s free are waves pour emblem fair— The pride of the Forest-land! [unnumbered page]

HAMILTON.

The reader who has yet to enjoy the pleasure of visiting the fair city of the West whose name heads our article, will perhaps fail to obtain from our frontispiece an adequate idea of the attractions of one of the most admired scenes in Canada. The artist has taken his sketch from an elevation commanding a bird’s-eye view of the city, which lies spread out like a map before him; but so much of the picture is taken in at a glance—over such a wide extent of hill and forest, water and plain does the eye range, that in order to compress it within the small space our sheet affords, the objects are so diminished as to mar in some degree the proper effect, and, faithful and well-executed as the picture is, it leaves the chief beauties of the scene to be discovered by an actual visit to the place itself.

It is, we trust, unnecessary to inform even the English reader of the whereabouts of Hamilton and Burlington Bay; but it is not every one informed upon this preliminary, who has also had an opportunity of witnessing the pleasant view which opens to you as you enter the harbour, or look down upon the lake from the commanding elevation of the “Mountain.”

Some good people, who have seen but little of Canada, and who are more fond of applauding what it is out of their power to see, than making the most of what is under their eyes, are fond of telling you that you must travel to Europe in order to enjoy the grandeur of really good scenery. We confess that we have never felt much sympathy for these discontented critics, who will hardly let you enjoy yourself in your own land, or within hail of your own fireside; and we cannot but thin k that the advocates of foreign travel would do well to see all that is worth looking at, of their own land, before they go abroad.

It was with some such thought in our mind, that we found ourselves carried swiftly through the new canal into the harbour of Hamilton. The narrow strip of land through which this canal passes, is a curious formation, resembling a bank erected by great labour and perseverance, rather than placed there by the hand of nature, so as to form a commodious land-locked harbour for the convenience of commerce. It runs straight from shore to shore, in many places not more than a couple of hundred yards wide, and with no outlet except the canal which has been cut through it, and which now renders the approach safe and easy to steamboat and schooner. [unnumbered page]

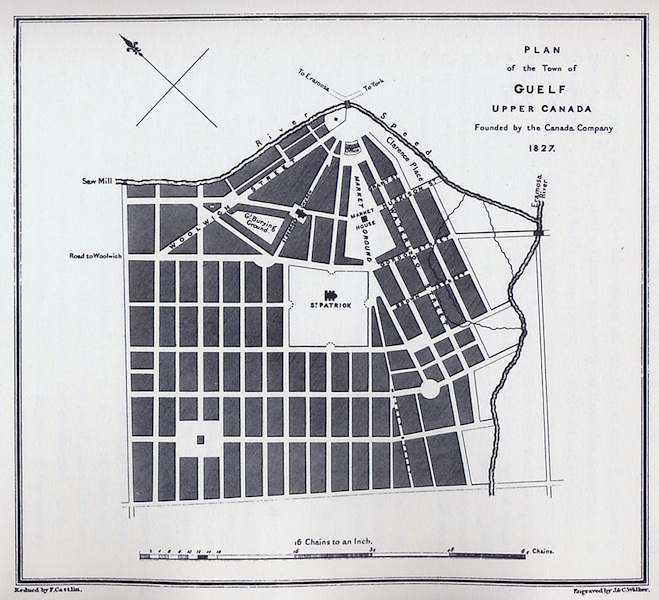

On the south side of the bay, under the shelter of the Heights, and spreading from the water’s edge some mile and a half inland, is built—or rather is being built, for its size is materially increased year by year—the city of Hamilton. The main portion of the town is that most remote from the water, having been built upon the high road from Toronto (then York) to Niagara—the latter being at that period the chief town of the Province—before the value of the water communication was felt, and when the only passage between the side of the present canal and the north shore, long since choked up, and level with the adjacent soil. The harbour having been made good, and a regular steam communication with the eastern ports established, the town is rapidly-spreading towards the wharves, which are approached by the long straight street shown in our plate, and which has recently been relieved from the infliction of periodical mud by the salutary application of Maeadam’s invention.

There are many points of view, from which Hamilton presents a pleasing scene; but our favourite one is from the height overhanging the town to the southward, which you ascend on the new road to Port Dover, on Lake Erie; and from this direction our view has been taken. Leaving the city, this road turns off to the eastward, and, forming a sharp angle, gains the summit by an easy ascent. The angle is about midway above the level of the town; and here we may pause, and see how much the prospect has already opened upon us, before we continue the ascent. Turn and look to the north and eastward. There is old Ontario, spread out before us in all the glory of its broad sheet—the bright blue surface gently ruffled with the light breeze of a fine autumn day, and glistening in the rays of the morning sun; while a few white sails pass slowly along shore, and a steamboat speeds merrily on her way to the sister city of Toronto. Any one not accustomed to look through a Canadian atmosphere, would be surprised at the range which the eye can take in this clear air. The shore is discernible the greater part of the distance to Toronto, which is more than forty miles from us. To the remotest horizon, objects, although diminished, are enveloped in none of that haze which ever baffles the spectator in the mother country—all is clear, and bright, and beautiful; and a “travelled man” would tell you, the air of Italy is scarcely more transparent, and certainly not so fresh and bracing. As we passed up the lake, the low north shore was visible; but from this elevation we see the back ground of forest-clad hills, with small gaps here and there, looking like mere garden-plots in the distance. These are farms, of hundreds of acres, with their houses, barns and comfortable homesteads. But this is only one portion of the scene. There is the long strip of land forming the boundary of the bay, and within it the pleasant pond of water—a mere pond, for Canada at least, but it would [unnumbered page] be a “loch” of considerable size and celebrity “at home”—mirroring the deep blue sky, and rivalling it in hue, and surrounded with a shore presenting in its alternation of wood and field, and variegated landscape, the aspect of a gigantic park, formed into terrace, and grove, and lawn, by immense labour and skill. But the labour of man has had comparatively little, and certainly not too much, to do with this scene—all-bounteous Nature is the gardener of the land. And beneath us is the town and the harbour, but these we shall see better from a higher position. On we climb, then, to the top of the hill, where the road turns, at an angle, through the cliff, and passes into the forest towards Lake Erie. Look now, north, east, and west and say if you have ever, even in all the travels which the home-stayers envy so much—if you have in all these seen many more beautiful or cheerful landscapes. Even Highland scenery can scarce compare with this; and the glorious landscapes of the fertile country seem from the Cheviots, if more luxuriant, yet surely contain far fewer comfortable houses, than does this range of hill and champaign. Look down upon the wide expanse of level ground between this almost perpendicular rock and the bay—the town covering an inconsiderable portion of it, large as it is. How bright and natural and cheerful it all appears! The scene which was one, and not so very long since, all nature’s own, is now bedecked with the works of active man, but his labours, energetic as they have been, have only beautified, not marred, the picture. The forest is cleared away, with the exception of such trees as are reserved for ornament; the valley, once clothed with wild woods, now wears the more appropriate covering of the green sward, and the busy hum of active trade now fills the air, which once echoed to no voice save that of the Indian. The town is, in fact, a thriving place, remarkable for the energy of its inhabitants, and the rapid increase of its trade. Who that has ever walked through its regular and well-built streets, observed its gay shops and handsome private residences, and noticed the activity and vigour which characterise the youthful city, can doubt that its present progress, great as it has been, is but the dawn of its future advancement and prosperity? In addition to its commanding position at the head of the lake-navigation, several main roads, leading from the fertile produce-growing country inland, centre here, and pour into its lap a large portion of the Western business. London, Galt, Guelph, Brantford, Paris, and Port Dover, are all reached by good roads, some of which are being rapidly extended further westward, so as to draw down to this port the exports of the new townships lately settled, and those now opening to the north and west; and all this, the Hamilton merchants are learning to carry direct to Montreal without transhipment—that is, so much is saved from the handling of our kind neighbours, who are so freely offering to relieve Canada of the trouble and the profit of her legitimate business. [unnumbered page]

But while talking of the fair city and its enterprising inhabitants, we are neglecting to look across the valley, to the magnificent bold outline of the opposite boundary. It does not rise abruptly from the level, like the hill on which we stand, but curves and undulates to its crest, affording space for farms, and even villages, upon the slope which now glows with the unrivalled tints which a Canadian autumn alone can bestow upon the forests, the rich colours mellowed into softness by the distance. That cluster of small objects glistening in the sun, and apparently embedded in the trees is the village of Ancaster, some eight miles from us, whence the London road descends to the City: and beneath the hill, but hid from view by the intervening woods, is the town of Dundas. Let the eye wander round again towards this side, and on the grassy shore of the bay, to the westward, we see Dundurn, Sir Allan Macnab’s residence, overlooking the noble basin of water in one of the loveliest spots on its banks. A tree in our Arists’s view, conceals the Castle behind its leafy veil. We annex, however, a faithful sketch of the front presented to Burlington Bay.

[illustration]

Altogether, the mountain, the lake, the town, and surrounding country—the whole immense amphitheatre, not desolate or barren, but full of life and pleasant beauty, and evincing every sign of thriving comfort, is such a prospect as ought to gratify and please every one that admires really beautiful scenery, and is capable of appreciating the blessings which such a country affords to all of its inhabitants who but exercise the ordinary virtue of industry.

What a change has come over the scene, since the time, when in sportive boyhood, disdaining the use of the half-finished road, we climbed this hill side, and looked [unnumbered page] upon the plain beneath! Houses and streets now occupy the fields, where we then saw the cradlers laying down the yellow grain, and gazed with astonishment on the wondrous rapidity with which the operation was performed—the stern face of the old Forest is dimpled with smiling meadows—and the corn-fields “laugh and sing” in the bosom of the wild woods. We now look upon the scene which presents itself with more than the wonder of a boy, or the criticising pleasure of the traveller; it is part of a country within which our lot is cast, and which, English as we are, we rejoice to call the home of our adoption. We look upon it, too, as additional evidence of the growing prosperity of the land, thinking not only of the City and the environs which we see, but of the astonishing abundance of the surrounding country, where you may see farm against farm appear, all teeming with plenty, so near together as to resemble a large garden interspersed with copses of forest, whilst nearly every hundred acres of those fair domains owns as lord the man who tills it. Another twenty years, and how many thousands more may share in the plenty and the blessings of this land, much more favoured as it is than thankless man is often disposed to own. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration]

[2 blank pages]

EDITH.

Why is that fair young brow in sadness shaded?

What pensive thought dwells in that deep blue eye?

Has some fond hope of thy young fancy faded?

Have Life’s spring blossoms bow’d their heads to die?

Perchance some loved one wanders ‘neath the sky

Of distant lands, unfriended and alone;

Brother or sire in danger’s path may lie—

The battle-field, where wounded thousands moan,

Or ocean’s azure depths may claim them for her own.

Is it that Love’s fond tale has reach’d thine heart?

Does soften’d sadness on thy spirit press,

To think the loved one comes to bid thee part

With childhood’s home—a mother’s fond caress?

To take thee where a husband’s love may bless—

But which when tried may wither, faint and cold,

Leaving thee lone in life’s dull wilderness,

A prey to sorrow, helpless, poor and old,—

Thy only solace tears, thy sighing uncontroll’d?

Whate’er the doubts that sadden now thy brow,

Whate’er the sorrows following thee through time,

Learn to seek happiness alone, below,

In Him who sits in heavenly place sublime.

Until thou reach that many-mansion’d clime;

Let thy whole soul be fill’d with faith and love;

Then when death comes—be it in age or prime—

On angel’s wing thou’lt soar to realms above,

Where tear hath dimm’d no eye—where passion never strove. [unnumbered page]

THE SEA! THE SEA!

Aκοίνηυητι βοẃντωυ τϖν στρατιϖτϖυ—ϴάλαττα, ϴάλαττα.

XEN. ANAB.

ϴάλαττα, ϴάλαττα—

For the light of thy waves we bless thee,

For the foam on thine ancient brow,

For the winds, whose bold wings caress thee,

Old Ocean! we bless thee now!

Oh! welcome thy long-lost minstrelsy,

Thy thousand voices, the wild, the free,

The fresh, cool breeze o’er thy sparkling breast,

The sunlit foam on each billow’s crest,

Thy joyous rush up the sounding shore,

Thy song of Freedom for ever more,

And thy glad waves shouting “Rejoice, rejoice!”

Old Ocean! welcome thy glorious voice!

ϴάλαττα, ϴάλαττα—

We bless thee, we bless thee, Ocean!

Bright goal of our weary track,

With the Exile’s wrapt devotion.

To the home of his love come back.

When gloom lay deep on our fainting hearts,

When the air was dark with the Persian darts,

When the Desert rung with ceaseless war,

And the wish’d-for fountain and palm afar,

In Memory’s dreaming—in Fancy’s ear,

The chime of thy joyous waves was near.

And the last fond prayer of each troubled night

Was for thee and thine islands of love and light.

ϴάλαττα, ϴάλαττα—

Sing on thy majestic pæan,

Leap up in the Delian’s smiles;

We will dream of the blue Ægean—

Of the breath of Ionia’s isles;

For the benefit of our lady-readers, we deem it fitting to state, that the subject of the foregoing lines is the historical exultation of the “Ten Thousand,” when, at the close of their memorable retreat over the hot plains of Asia, they caught the first welcome glimpse of the sea, that foamed and sparkled in the distance. [unnumbered page]

Of the hunter’s shout through the Thracian woods, Of the shepherd’s song by the Dorian floods; Of the Naiad springing by Attic fount, Of the Satyr’s dance by the Cretan mount, Of the sun-bright gardens—the bending vines, Our virgin’s songs by the flower-hung shrines; Of the dread Olympian’s majestic domes, Our fathers’ graves and our own free homes.

RICE LAKE BY MOONLIGHT.

A WINTER SCENE.

Moonlight upon the frozen Lake! how radiantly smiles The queen of solemn midnight upon all its fairy isles, And the starry sparkling frostwork, that like a chain of gems Hangs upon each fair islet’s brow in glittering diadems. How stilly lies the sleeping lake, how still the quiet river, As though some wizard-spell had laid their waves at rest for ever; Murmurs abroad the hoarse night-wind, waves every leafless tree— Yet not one ripple stirs thy breast, oh! proud Ontonabee.* How strange it is, this death in life, this mute and stirless show, While we know the prisoned waters are heaving yet below, Like the cold, calm look the strong mind may to lip and brow impart, While ceaseless care, like canker-worm, is gnawing at the heart. Light, but no warmth—a dancing gleam—while all is cold beneath; Like the sweet smile that mocks us yet upon the face of death; While yet the dead lip wears so much of beauty and of bloom, We scarce can look on it and think of darkness and the tomb. How quiet, in the moon’s pale light, the tiny islands lie, Down-looking to the waveless lake, up-gazing to the sky, Slumbering beneath her holy beam, like children lull’d to rest, Watch’d by a mother’s loving eyes—upon that mother’s breast.

* The Ontonabee River, which supplies the principal portion of the waters of the Rice Lake. [unnumbered page]

Awake, awake, oh! sleeping lake, at the wild-spirit’s call— Wake in thy summer joyousness, shake off the Frost-King’s thrall; For back to wood, and stream, and brake, glad spring returns once more, And thy mercy waves shall break again in music on the shore. How many changes hast thou seen, since first the sun-beam’s smile, Through the dim-twinkling forest leaves, glane’d down on wave and isle, Ere yet upon thy sunny banks a mortal footstep trod, Or any eye had looked on thee, except the eye of God. The dusky tribes that knew thee first, have vanished from the scene, And scarcely left a wreck behind to tell of what hath been; Yet still through time, and chance, and change, smile the fair lake and river, As pure, and bright, and beautiful, and shadowless as ever. Man dies, and is forgotten, his monuments decay, His very memory passes like a dream of yesterday; But the glorious trophies of His might that God himself hath plann’d, Till Earth and Heaven pass away, unchangeable shall stand.

“COME TO THE WOODS.”

Come to the woods—the dark old woods, Where our life is blithe and free; No thought of sorrow or strife intrudes Beneath the wild woodland tree. Our wigwam is raised with skill and care In some quiet forest nook; Our healthful fare is of ven’son rare, Our draught from the crystal brook. In summer we trap the beaver shy, In winter we chase the deer, And, summer or winter, our days pass by In honest and hearty cheer. And when at last we fall asleep On mother-earth’s ancient breast, The forest-dirge deep shall o’er us sweep, And lull us to peaceful rest. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration]

[2 blank pages]

GIBRALTAR.

What time the moon led in her glittering train

Of heaven-lit torches through the realms of night,

Methought that sleep had loosed my spirit’s chain,

And, freed from thraldom, swift it winged its flight,

Where oceans twain, o’erhung by Calpe’s height,

On either side in slumbering beauty lie;

The shores of our renowned for deeds of night

And high emprise—of fame, that ne’er can die

Till fleeting time is lost, merged in eternity.

The outer sea was boundless deemed of yore,

Haunted by phantasies and forms of gloom;

No daring bark e’er ventured from the shore,

For all was dark, like heathen’s thought of doom,

Whose fears and hopes are buried to the tomb.

High on the peak above those twin-born deeps,

My wand’ring spirit saw bright visions loom

Of fam’d exploits of Eld, which memory reaps

From history’s boundless field, and safely garnered keeps.

And truly in the world’s wide range, the poet could not take his stand on a point more replete with spirit-stirring associations; on no other “cliff, or isle, or rocky steep,” could he more successfully evoke with magical wand, from the mists which enshroud the past, the memories of mighty deeds—“the famed exploits of Eld.” Again are the fantastic dreams of the old mythology enacted; through the witcheries of fancy he beholds the warlike hero severing the lofty rock, and wedding two oceans; anon in anger hurling his brazen shafts against the fire-raining Sun-God, who, admiring his more than mortal courage, complacently lends him his golden cup to stem the ocean streams. Again are seen the world-weary visionairies of Greece and Rome, straining their wistful eyes from the rocky steep across the unknown ocean, earth’s western bound, striving if perchance they might catch a glimpse of the Blessed Isles in the distant offing—happy Isles, where neither sorrow, nor pain, nor satiety ever intrude, where perpetual spring reigns, and where no flitting clouds of care obscure for a moment the sun of perfect happiness.

But it is not to these fanciful, old-world dreams, that the promontory is indebted for the romantic halo which invests its name, gorgeous as one of the sun-lit clouds which oft hang its towering peak.

For lo! unnumbered brazen galleys wing

To Calpe’s caverned rock their onward flight

And on the decks stands many a Moorish king,

With flaming shield and nodding plume bedight,

All armed t’ avenge lorn Cava’s hapless plight;

In mists obscure is lost the warlike scene,

And rises now a sad yet gorgeous sight,—

The Paynim crescent gleams with silv’ry sheen

O’er myriad towers and domes, where once the cross had been. [unnumbered page]

When the outraged Cava was torn away from her mountain home by the despotic King Roderic, Count Julian for a time dissembled his fiery indignation, until he head formed a scheme of evenge, with which the whole world should ring. Slowly and cautiously he carried on his intrigues with the Moors on the African coast, until at length, his plans being completed, he gave the signal, and hordes of simitared Paynim warriors, the pride of Soldanrie, swept like a fiery torrent over the plains of sunny Spain. Roderic was slain on the field of battle—the gallant chivalry of Christendom was scattered, after many a hard-fought fight,

“That dyed the mountain streams with Gothic gore,”

and for six hundred years the cross was trampled in the dust by the turbaned unbelievers. In this invasion , Calpe was the first Spanish point on which the invaders landed; and Tarik, the leader of the land, called it after his own name, Gibel-Taril—the Rock of Tarik—since softened into Gibraltar.

Until the fourteenth century, the Moors kept possession of this point, having erected a strong fortress on the north side of the mountain, the ruins of which remain to the present day. From Henry IV, king of Castile, it received the appropriate arms which it at present bears—a castle with a key hanging in the gate; but to Charles V it was chiefly indebted for those strong fortifications, which rendered it really the key of the Mediterranean.

In the war at the beginning of the last century, this gigantic citadel of nature fell into the hands of the English nation, more through fortuitous circumstances, than by any well-natured plan of operations. A fleet, under the command of Sir George Rooke and the Prince of Hesse Damstadt, was sent to cruise in the Mediterranean. Having failed in their immediate object, and dreading to return to England without having accomplished some brilliant exploit, they suddenly determined to attack Gibraltar. The resolution was carried into effect; and after a few hours’ bombardment the citadel was taken, and the flag of England hoisted, never we trust, to be lowered again.

Within a few years of this event, vigorous attempts were made to restore this invaluable jewel to the Spanish crown, but in every instance the assailants were signally defeated.

Mortified by these repeated failures, the Spanish nation took the opportunity when England was engaged in war at once with France and America, to commence hostilities against the Queen of the Seas, in the vain hope of recovering their lost stronghold. In the middle of June, 1779, Gibraltar was blockaded. At this crisis, fortunately, the fort was commanded by General Elliott—an officer fully equal to the emergency, being possessed of every high quality that should adorn a military man. And fearful was the ordeal through which he had to pass. The rock being [unnumbered page] completely cut off from the adjoining coast, provisions became exceedingly scarce—a tremendous fire was kept up, with but little intermission, by the combined forces of France and Spain—and, to increase the horrors of the scene, the small-pox broe out in the town with extreme virulence.

And now supreme grim Famine holds her court, And Pestilence—her sister—stands full near, Within the walls of the beleaguered fort, Striving to crush with all their portents drear Those iron hearts that never quailed through fear. And oft, like ghastly phantoms of the night, The dauntless veterans on the cliff appear, To scan th’ horizons with fast-dimming sight, And pray for England’s aid in such unequal light.

Thistles, wild leeks and other weeds, were greedily sought for sustenance; and the brave old Governor, to try the experiment on how small an allowance of food life could be preserved, restricted himself for eight days to four ounces of rice per day. For three years this heroic man sustained the drooping spirits of his soldiery, amidst the scenes of horror by which they were surrounded. Three or four times, British frigates daringly broke through the blockade, and supplied the starving garrison with provisions, when reduced to the most fearful extremities. It was during one of these welcome visits, that the sight of His late Gracious Majesty King William the Fourth, then acting as a midshipman, elicited the remark from a distinguished Spanish prisoner. “No wonder that the English nation has gained such a naval superiority, when one of the princes of the blood royal is seen serving in so humble a position.”

Towards the close of the third year, the enemy prepared for a grand effort. Forty-seven line-of-battle ships took up their positions on the southern and western sides of the promontory, together with battering-ships the strongest that had ever been constructed, and a great number of frigates and smaller craft; while on shore there lay a body of 40,000 troops, behind batteries lined with 200 pieces of the heaviest ordinance.

On the British side, the whole force amounted to less than 7,000 men.

In this perilous condition, it was fortunately suggested by General Boyd, one of the officers of the garrison, that red-hot shot should be used against the assailants.

His suggestion was acted upon, and presently a scene of frightful sublimity was witnessed. Streams of fire seemed to pour down the steep, while the roar of so many hundred pieces of artillery made it tremble as if shaken by an earthquake.

As raging Ætna’s molten torrents stream, Adown the rock the fiery volleys sweep, And death-winged dazzle with a lurid gleam; Then swift the blazing fleets illume the deep, While smoke and sulphurous vapours heavenwards creep, Shrouding the scene in vast funereal pall— But Albion’s flag still floated o’er the steep Where proud Urwin leagured with boastful Gaul, Fell by the vengeful wrath of those they would enthral. [unnumbered page]

Dense clouds of smoke soon burst from the enemies’ ships—flames glided along the rigging like glittering serpents—and speedily the whole fleet was enveloped in sheets of fire. But amidst the thunders of exploding magazines, and the pealing of the guns as the flames reached them, were heard the shrieks and grans of the unhappy crews; and the British soldiery, ever humane as brave, hurriedly put off in boats to rescue their fallen foes from destruction.

Since that period, no enemy has dared to attack this fortress. There it stands, like a grim sentinel, keeping watch over the rich and fertile lands engirdled by, and the beautiful and fertile islands scattered over the tideless Mediterranean.

Calpe, thou giant warder of the main! Time hath not minished aught thy stately mien; Though fallen nations own the tyrant’s reign, Which erst in towering stateliness were seen; Of Albion art though emblem meet, I ween— Unconquered Albion, changeless as that sea Which, vassal-like, defends the Island Queen!— As winter’s storms beat harmlessly on thee, So ages leave unscathed the “Empire of the Free.”

CHANGES OF AN HOUR

ON LAKE ERIE.

Smiles the sunbeam on the waters— —On the waters glad and free; Sparkling, flashing, laughing, dancing— Emblem fair of childhood’s glee. Ruddy on the waves reflected, Deeper glows the sinking ray; Like the smile of young affection, Flushed by fancy’s changeful play. Mist-enwreathing, chill and gloomy, Steals grey twilight o’er the lake— Ah! to days of autumn sadness Soon our dreaming souls awake. Night has fallen, dark and silent, Starry myriads gem the sky; Thus, when earthly hopes have failed us, Brighter visions beam on high. [unnumbered page]

ROUGH SKETCHES BY A BACKWOODSMAN.

“There are fairer fields than ours afar, We will shape our course by a brighter star, Through plains whose verdure no foot hath press’d, And whose wealth is all for the first brave guest.”

“A life in the woods for me.”

OLD SONG.

In the pages of the “MAPLE-LEAF,” the beauties of some of the fairest landscapes of this land of our adoption have been depicted in fresh, but not too brilliant colours, and there is yet ample room for the exercise of pen and pencil in the same agreeable and useful employment. But there are other scenes, the description of which may not be wholly uninteresting, whether to the emigrant, who is yet but beginning his experience among them; or to the gentlemen, who remain “at home at ease,” and hear only of us and our country in the distance; or even to the old settler, who amid his ever-recurring avocations has found but little leisure to analyze very closely the peculiarities of a life now become familiar to him. These are the scenes not of Canadian hill, and dale, lake and forest, but the home pictures of every-day life, as it may be seen by the close observer in our villages, and farms, and backwood settlements.

At the outset, we must warn the kind reader, who wishes to accompany us whilst we sketch from nature, that it is on no picturesque tour we purpose taking him. Homely are the scenes which we shall visit, and familiar the features which we intend to portray. Our course will lead us not through “tangled brake” or by “sequester’d stream,” nor yet along the smooth highways of city life, but over the rough roads, that lead far from the refinements of “the front,” to the rude simplicity of our “back settlements.”

Here we are, then, in a country village. There is something old-country-like in the words; and the place itself, situated on a river bank, so as to take the best advantage of the “water privilege,” looked really beautiful as we approached it. But you are evidently disappointed on a closer inspection. That hewn log-house, which looked so white and pretty as you passed the turn of the road, now appears in its true [unnumbered page] character, decidedly out of the perpendicular, and leaning, as it were, affectionately towards the stream; but if you must needs be critical, look a little further on, and you will observe that a new house is being built on the same premises, and of brick too, so we will not be very severe in our censure of that which is about to be deserted. The village, in fact, consists chiefly of two rival taverns—ditto of stores, and the blacksmith’s shop. You need not entertain an unfavourable opinion of our “settlers,” because you see some loungers about the inns, the real men being at work in the fields. Look a little to your right and to your left, and you will see that the mills are going briskly, and that a fair business is doing at those stores in grain and produce, and there is an air of decided independence among the people whom you see busy about the emporia of the country, which gives you an idea that distress and poverty are maters unheard of in these parts. And so in fact they are. This land feeds all her people. Those mills are the property of a man who came to Canada, to seek a living, and with scarce a sixpence in his pocket. His capital consisted of a stout frame, industrious habits and good principles. He has now settled his family, not as cotters, but as farmers and merchants, and has one of them in partnership with him in the mill business. He has called the “land after his own name,” and we now stand in ————, whither, this thriving proprietor will inform you, he came some fifteen years ago, when a footpath through the woods was his only guide to the spot. Well has he prospered since, although, strange as it may appear, he is not what would be ordinarily called a good man of business. During the long evenings, you may see him poring over pieces of paper of various shapes, and covered with characters not formed exactly after the model of the writing master, and a dingy book or two, which give him much more information as to the state of his affairs than you would imagine. A lawyer or bankrupt’s assignee would have some trouble in striking a balance-sheet from these materials; but as our friend never speculates more deeply than present means warrant, in his mill business, and has never yet been engvaged in lawsuit, there is no reasonable probability of any sharp-eyed disciples of Gamaliel being troubled with the adjustment of his affairs. Half-educated as the man is, his prudence is a practical rebuke to that description of persons who, with much better opportunities of learning, fail to gain sufficient wisdom to carry them safely through life. You need not travel far through Canada, without meeting with men who will abuse everything in it. They will say, this business will not succeed, and that is sure to ruin you. Enquire a little further, and you will find that they have foundered their own ships by loading them too heavily. Speculations entered upon without experience, and frequently, singular enough as it is, without capital, can scarcely be expected to lead to wealth, even in Canada. [unnumbered page]

Passing to a respectable distance from the bustle of the “Street,” as the highroad is curiously called hereaway, we find ourselves abreast of the new village church. This evinces the real progress of the place; and if you are going to locate yourself in the remoter parts of the bus, it may be some time ere you look on as cheering a sight again; and the recollection may iduce you early to apply you own energies, and induce your neighbours to do likewise, towards obtaining the blessings of the Church’s ministrations in your own backwood settlement.

Let us now cross the stream, and travel some distance along this new rough road, where you shall see how farms are made, and how serviceable that land is rendered when the old giants of the forest are removed, after shedding their leaves for centuries of autumns. Here is one of the best specimens of a backwoods farm, and we will make a closer inspection of it than we have done of those which we have as yet seen. It might puzzle you to hold a plough among those gnarled and irregular stumps, and the tough scarce-hidden roots which occupy the soil; but the farm is a very valuable one, notwithstanding that the clearance was only commenced si years ago, and the country is still called “the bush.” The house, you observe, is built of logs, not hewn as you saw them in the more pretending village residences, but the plain trees, round and in their bark as they grew. The walls are, however, nearly laid, the corners regular, and the crevices carefully filled with plaster. You may often know the idler by his slovely-finished dwelling. Your “new-comer,” who is fond of telling you how handsome was the house he lived in “at home,” appears to think that, because he must now see some of the roughs of life, the roughr and more uncomfortable he can have everything about him the better. Watch the man closer, and ten to one, but you find he has an equally bad excuse for shirking the work of his farm and other useful occupations. He tells you that “this is the way in Canada”—“nothing better in this precious country, you know”—and perhaps proceeds to edify you with an account of hardships which would not frighten a lady, and to tell you of English comforts which, although you have not seen salt water these twenty years, you know more about than he does. The sensible man in yonder house, on the contrary, fills up every spare hour by doing something useful—completing a window-frame, or making another table, or an original patterned easy-chair for “mother”—rendering all about him more comfortable every day, and thanking Providence that he is in a country where timber costs nothing, and where there are no taxes upon glass, and very few upon other necessaries. His chimney is of clay, it is true, but it is squared and smoothed, and will be whitewashed soon; and the ascending smoke gives as cheery an earnest of the dinner, to which we, as strangers and travellers, shall be welcome, as if it ascended through a stack of real brick and chimney-pots. [unnumbered page]

And now that we have experienced the bushman’s hospitality, and tasted his dish of well-cured bacon and potatoes (the latter of which, by the way, you must admit could scarcely be surpassed in Ireland), I will endeavour to give you some idea of his mode of life. Fortunately for the good man, he has several stout youths to assist him in his labours, and they soon learnt to chop and clear land. This done, the farming was a matter which he understood better than his Canadian neighbours, and somehow his fields soon presented an appearance which attracted the attention of the other backwoodsmen. Not a foot of ground is lost, except that which the stumpts actually cover, and the barns which he has built are filled to overflowing. This man has “seen better days,” but he is most cheerfully contented and happy with those which he now enjoy. He has every comfort about him, and is never heard to grumble about what “we used to have in the old country.” He grows better wheat than he did in Britain, and has no rent to pay out of the proceeds of it. He has few wants, and those few are well supplied, and he has no taxes nor poor-rates to trouble him. He not only enjoys these blessings, but appreciates them. You observed the cheerful housewife who presided at the clean, well-furnished table. She had the air of a lady; and the fact is, she is such both by birth and by education, and joins to the accomplishments which grace the drawing-room, a thorough knowledge of the mysteries of housewifery, and perfect acquaintance with the management of the dairy. Her acquirements she does not make use of for the purpose of display, or of showing how flippantly she can contrast her present position and the society with which she is surrounded, which those of other lands and earlier life, but turns her knowledge to the more useful purpose of instructing her young family. Had we accepted her polite invitation to remain until morning under the roof, you would have seen her, notwithstanding the stranger’s presence, giving the young children their evening lesson, and catechising the little flaxen-haired fellow you were playing with, in the simplest rudiments of that knowledge, without which all else is ignorance; and we should not have separated for the night, without hearing from the lips of her husband a chapter modestly but well read from the “bug ha’ bible, ance his father’s pride.” The great secret of that family’s happiness—and you must admit they looked happy as well as comfortable—is, that such a sin as Idleness is unknown among them. All are ever employed, sometimes in labour sufficiently trying to the constitution both of the father and his striplings; but Plenty crowns their exertions, and the peaceful rest of the fireside sweetens their life. Such can back-woods life be made by the humblest settler.

I see you wondering who can be the owner of the farm which we are now reaching. It is a wilderness of a place to be sure, and the house and barn are scarcely distinguishable from the other. You can now be certain; for you observe that one end of the longest log building has a window and a chimney in it, a portion of the [unnumbered page] remainder being evidently filled with some produce of the field. That is the “estate,” we suppose we must call it, of a family of high respectability; and the exceeding great pity is, that they have very greatly mistaken their vocation. They are highly connected “at home;” but the neighbours, whose ability to labour has enabled them to far outstrip the gentleman in point of wealth and comfort, have not the slightest idea of rendering him any respect on account of his noble blood or illustrious pedigree. None of them are his tenants, but I am sorry to say a few are his creditors for certain supplies, which they aver with some ill-humour they could have marketed more advantageously in the city, very far distant as it is. We will not call here, because, although we should be both courteously welcomed and hospitably entertained, you would be painfully conscious that the family would either not see company, feeling, as they do, the unpleasantness of the change in their mode of life, and galled by their altered circumstances.

This gentleman came here possessed of a capital which might have produced a fair annuity. Although utterly inadequate in England, it was yet sufficient to have maintained him in comfort in Toronto, where he could have obtained for his boys education of the highest order, at a trifling expense, and then have found openings for them without difficulty in respectable lines of life. But to live a reduced gentleman among a people who can neither understand him nor make themselves understood by him. Rather than submit to lower his head a little in his own element, he tries to move in an element quite foreign to him, when he gets laughed at by those whom he has been accustomed to consider his inferiors. Some hard lessons are often learnt in the woods, and this gentleman has been favoured with no small share of them. Contrary to the scorned advice of the other bushmen (for he came to teach, not to learn), he has built a log house so large that it could not but sink and settle out of shape in a couple of years, and which he has never found it convenient to finish. Then he sets to work clearing land; and supposing that a farm must needs consist of several hundred acres, he gave a contract to clear fifty to begin with. This done, he found it impossible to cultivate more than the half of it, and that badly, while the “second-growth” underbrush choked up the remainder. He laboured industriously, with the assistance of his delicate-fingered boys, to make the farm pay; but it was impossible, and he now finds himself nearly stripped of his money, and his children half-a-dozen years older than when they left school, without a dozen new useful ideas added to their former stock. Had this gentleman been advised to enter into business as a Liverpool cornfactor, instead of embarking for Canada, he would have frankly said, he knew nothing about the business, and the attempt would be ridiculous. The same truth does not seem to have occurred to his [unnumbered page] mind, with regard to hard manual labour and Canadian farming. In another year or two, you will find him perhas, if he is fortunate, the acceptor of a small Government employment, enjoying intercourse with the inhabitants of the city, in which his official duties require him to reside, and at last convinced by experience, that there are others in Canada besides his own family who possess the characteristics of good society, and who actually understood manners and etiquette long before he formed the project of enlightening the ignorant colonists on the subject. One of his sons will obtain a commission in the army, where his loss of school benefits will not be severely felt; and the others, by dint of the hardest labour, may possibly so far retrieve their time as to fit them for the counting-house or the professions. And if they do, they will be more fortunate than many of their class.

But I observed that you particularly noticed that young man, driving the ox-team which passed us just now. Handsome he still is—and his bearing is that of a gentleman. The effect of bad habits, however, is plainly and deeply traced in his countenance and general appearance. A chapter of his history might be a warning to some unthinking parents in the old country who would settle their promising boys in the Canadian backwoods. The youth came here with a good outfit, and found ready for him an hundred acres of huge trees. He had permission to draw for an occasional twenty-five pounds rom the paternal bank; and he was indulgently expected to make, not a living exactly, but considerably more, out of the said hundred acres of land. He took up his residence in a small log house upon one corner of the “demesne,” and kept bachelor’s hall in a manner which would have astonished his dear mamma, both by the absence of all proper comfort, and the too frequent presence of companions who would not have been so much at ease in a drawing-room. A few acres of land having been cleared, it soon became evident that although our hero was strong of frame and had learnt to chop and plough, he could not book a large dividend upon his capital invested. After lingering on in this manner for three or four years, during which he has become weaned of most of his good manners, and, sad to say, some of his good principles, he finds the supplies stopped. The kind father has met with losses; and even if he could afford to honour more drafts, he seriously thinks that if Canada cannot make a man independent in three or four years, the dear boy might almost as well have gone to the distant paradise of Australia. Had a friend suggested to the worthy gentleman to establish his son as a tenant farmer in Devonshire, he would very sensibly have replied, that Thomas was a good Greek scholar to be sure, but you might as well expect him to command a man-of-war as to manage a farm. So he sends the stripling to Canada, to farm there, although the undertaking requires all the knowledge of the English farmer, which to make the farm, lay out money judiciously, ensure moderate returns, and [unnumbered page] make no losses by fishing after large profits which can never come—all this requires forethought, judgment and experience, which few men can acquire without long as well as close observation. Had the youth been allowed a small sum per annum, to pursue a line of study consonant with his tastes and former life, he might by this time have fairly commenced a successful career in business. Some lads in similar positions succeed well enough, but it is by the exercise of more enterprise and industry, than most youths possess. No young man in America must tolerate a stand-still life; he must determine to mount the ladder, and he will succeed, provided he has a sturdy frame, and the spirit to undertake anything “for an honest living.” This youth will perhaps work his passage home in a merchantman this “fall,” and delight the eyes of his friends. They will take his adventures to find that two of his brothers, who were equally ill-used, have prospered surprisingly; one of them, having become a thriving merchant, and the other being in the receipt of a competent livelihood in one of the “learned professions.” By means of hard work alone (the precious metal of America), these lads have effected what could scarcely have been done in England so cheaply.

Among these hints of what may be seen in the woods, some of our readers would perhaps like to hear of the pleasures of the chase—the glorious sport of gun and dog, among the quadrupeds and bipeds of the primeval forest. As we draw our pictures from the life, however, those readers will be disappointed. The “backwoodsman” (poor DUNLOP, of much respected memory, to the contrary notwithstanding) should reckon upon no such recreation. He will find hunting part of his employment, truly enough; but it will be what is called in the lingua loci “hunting cattle,” and consists of walking through several miles of forest once or twice a day, in search of his horned animals, who are regaling on the “bush feed.” In these rambles, if he thinks he is worth his while to carry a gun, he may perchance in the course of the season bring down a buck or two; but he will be glad to leave his gun at home, and travel light, for his day’s regular labour teaches him to economise his strength. Game may sometimes, too, be bad for searching; but the genuine backwoods farmer cannot spare time for this, and time is here our capital, which we must husband as a banker does his bullion. After a few years, the initiated backwoodsman will vow with a clear conscience, that the best sport he has is among his own flocks, and the slaying of a beeve of his own rearing and fatting, more pleasant and profitable than all the time he has ever spent in chasing deer or “treeing” partridge.

But you are tired—it is too evident—most indulgent reader. Canadian bye-roads are direfully rough, and plunging into mud-holes far from agreeable. We shall stop, then,—but first, we are bound in justice, both to our country and to our friends [unnumbered page] abroad, to say, that no greater error can be perpetrated, than to suppose Canadian life differs from life at home, in any of those essential particulars which render it necessary or even just to measure the means of success here, upon principles other than those applied in England. Do you want to be a Canadian farmer?—consider whether you can make yourself a farmer fit for England or any other country. Do you think of opening a mercantile house of any kind, in Canada?—answer the question, whether or not you can manage a similar establishment in London, Liverpool, or Glasgow? Are you living in retirement upon a small annuity, insufficient to give you the comforts and society your family are accustomed to, and dead living abroad, because it would oblige you to learn foreign habits and tolerate foreign faces?—you may rest assured, that the same money, which is but a scanty pittance where you are, will make you comfortable here, and surround you with a society as thoroughly Enlgish as that in which you now move. You want to educate your sons like gentlemen, and here you can do so with three, for less than one would cost you in dear England. But if you are provided with all these comforts, and heave no more idea of farming than of writing Hebrew, you will do well not to settle in the woods until you have looked well about you. But if, after thoroughly learning what a backwoodsman’s life is, you are sure you can “stand the work,” and not flinch at the few trifling inconveniences, then, by all means, come and share its enjoyments, which are not few, as well as the homely fare of “a backwoodsman,” who has endeavoured to instruct and perhaps entertain you with these few rough sketches.

We have said that the scenes of CANADA resemble those of HOME. So indeed they do, and in many instances excel them, if we may judge by applying the principle, that “that state of things is best which affords the greatest happiness to the greatest number.” Visit our cities, and observe the English-looking shops and streets and people. Step into one of our churches—and thank Heaven that you may utter the same words—breathe the same prayers—hear the same truths preached, as you have done from your childhood. Walk among the close net-work of country roads which intersect our well settled countries, and observe a homestead of comfort, neatness and independence, on every hundred acres of land. The untaxed, unrented soil yields the fruits of the earth in profusion—the barns groan with fullness, and the orchard trees bow their laden branches to the luxuriant grass. Look at all these things, and a thousand more as good and pleasant, and you will perhaps be induced to thank Providence for providing such a land, through which the Saxon race may almost indefinitely spread civilization and happiness. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration]

[2 blank pages]

THE TWO FOSCARI.

Ho! gentlemen of Venice! Ho! soldiers of St. Mark! Pile high your blazing beacon-fire, The night is wild and dark. Behoves us all be wary, Behoves us have a car No traitor spy of Austria Our watch is prowling near. Time was, would princely Venice No foreign tyrant brook; Time was, before her stately wrath The proudest Kaiser shook; When o’er the Adriatic The Wingéd Lion hurled Destruction on its enemies,— Defiance to the world. ‘Twas when the Turkish crescent Contended with the cross, And many a Christian kingdom rued Discomfiture and loss; We taught the turban’d Payaim— We taught his boastful fleet, Venetian freemen scorned alike Submission or retreat. Alas, for Venezia, When wealth and pomp and pride —The pride of her patrician lords— Her freedom thrust aside; When o’er the trembling commons The haughty nobles rode, And red with patriotic blood The Adrian waters flowed. [unnumbered page] ‘Twas in the year of mercy Just fourteen fifty-two —When Francis Foscari was doge, A valiant prince and true— He won for the republic Ravenna—Brescia bright— And Crema, aye, and Bergamo Submitted to his might: Young Gacopo, his darling —His last and fairest child— A gallant soldier in the wars, In peace serene and mild— Woo’d gentle Mariana, Old Contarini’s pride, And glad was Venice on that day He claimed her for his bride. The Bucentaur showed bravely In silks and cloth of gold, And thousands of swift gondolas Were gay with young and old; Where spanned the Canalazo A boat-bridge wide and strong, Amid three hundred cavaliers The bridegroom rode along. Three days were joust and tourney, Three days the Plaza bore Such gallant shock of knight and steed Was never dealt before; And thrice ten thousand voices With warm and honest zeal Loud shouted for the Foscari, Who loved the commonweal. For this the Secret Council— —The dark and subtle Ten— Pray God and good San Marco None like may rule again! Because the people honoured, Pursued with bitter hate, And foully charged young Giacopo With reason to the state. [unnumbered page] The good old prince, his father, —Was ever grief like his!— They forced, as judge, to gaze upon His own child’s agonies; No outward mark of sorrow Disturbed his awful mien— No bursting sigh escaped to tell The anguished heart within. Twice tortured and twice banished, The hapless victim sighed To see his old ancestral home, His children and his bride; Life seemed a weary burthen Too heavy to be borne, From all might cheer his waning hours A hopeless exile torn. In vain—no fond entreaty Could pierce the ear of hate— He knew the Senate pitiless, Yet rashly sought his fate; A letter to the Sforza Invoking Milan’s aid, He wrote, and placed where spies might see— ‘Twas seen, and was betrayed. Again the rack—the torture— Oh, cruelty accurst!— The wretched victim meekly bore— They could but wreak their worst; So be but a in Venice, Contented, if they gave What little space his bones might fill— —The measure of a grave. The white-hair’d sire, heart-broken, Survived his happier son, To learn a Senate’s gratitude For faithful service done; What never Doge of Venice Before had lived to tell, He heard for a successor peal San Marco’s solemn bell. [unnumbered page] When, years before, his honours Twice would he fain lay down, They bound him by his princely oath To wear for life the crown; But now, his brow o’ershadowed By fourscore winters’ snows, Their eager malice would not wait A spent life’s mournful close. He doffed his ducal ensigns In proud obedient haste, And through the sculptred corridors With staff-propt footsteps paced; Till, on the Giant’s Staircase, Which first, in princely pride, He mounted as Venezia’s Doge, The old man paused—and died. Thus govered the patricians When Venice own’d their sway; And thus Venetian liberties Bexame a helpless prey; They sold us to the Teuton, They sold us to the Gaul— Thank God and good San Marco, We’ve triumphed over all! Ho! gentlemen of Venice! Ho! soldiers of St. Mark! You’ve driven from your palaces The Austrian cold and dark! But better for Venezia The stranger ruled again, Than the old patrician tyranny, The Senate and the Ten. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration]

[2 blank pages]

THE BANK OF IRELAND.

“Relic of nobler days, and noblest arts,

Despoil’d, yet perfect!

* * * *

When the low night breeze waves along the air,

Then in this magic circle raise the dead:

Heroes have trod this spot—‘tis on their dust ye tread.”

CHILDE HAROLD.

The Bank of Ireland,” say you? Let me look a little closer; the eye of age is dimmer than its memory, and years have passed since last I looked upon the majestic pile. True, true, there it is! Your artist has hardly done justice to his noble subject, or, perhaps, the pride and prejudice of an old Irishman have stamped on his heart too fair-drawn a remembrance of the brave old council-hall of fifty years since.

Yes, there is it!—the faultless colonnades of the southern front, with their double line of stately columns, and in the remote distance to the right barely enough to recall the splendid portico of the Peers resting on its Corinthian shafts. I see it all—more than your artist has traced, and in the depth of a Canadian forest feel the bright recollections of youth and early manhood warming the old man’s heart. I have seen it in every aspect, in every light, in every shadow—with the bright soft morning sunshine of an Irish June lighting up on its noble aisles, as we hurried at the early chapel-bell towards the gate of old Trinity—in the stir and bustle of the afternoon session, as the noisy mob gathered round the approaches to cheer in wild chorus for Grattan, Conolly or Ponsonby, or to bandy sharp jokes or sharper yells at Fitzgibbon or Castlereagh; but—purest and fairest aspect—I have often gazed at it in the beauty giving lustre of the solemn moonlight. How often, as I wended my way homewards from the pleasant firesides of friends long since departed, but unforgotten, have I paused on the approach from Grafton-street, and gazed admiringly on the familiar but ever noble scene around! To the right frowned the stately western front of the University, in deep black shadow; to the left rose the proud effigy of the victor of the Boyne, on his tall war-horse; and away to the north and east swept the splendid columns, and arches, and glittering porticoes of the Parliament House—here a line of pillars, white and glistening in the rich moonlight—there a mass of black shadow, [unnumbered page]

“The Parliament-house was meant to be built during the administration of John Lord Carteret, in the year 1729, in the reign of George H., and was executed under the inspection of Sir Edward Lovel Pearce, engineer and surveyor general, but completed by Arthur Dobbs, Esq., who succeeded him in that office about the year 1739: the expense amounting to £40,000.

“The House of Lords, having for a considerable time been considered inconvenient by its members, from its too great interference with the Commons, it was determined to give it a distinct entrance, with some additional rooms. Accordingly, in the year 1785, Mr. James Gaudon, architect, was applied to, to make designs for an eastern front, with additional rooms, for the greater convenience of the Lords. His plans being approved, they were speedily put into execution, and are now entirely completed, to the great convenience of the upper house, and exterior ornament of the place. A noble portico of six Corinthian columns, three feet six inches in diameter, covered by a handsome pediment, now gives the noble peers entrance to the High Court of Judicature. The entablature of the old portico is continued around the new; but the columns of one being of the Ionic order, and those of the other of the Corinthian, an incongruity in architecture takes place, which is certainly exceptionable, and might have been avoided by making the whole of the same order.

“The two porticoes are annexed together by a circular screen wall, the height of the whole building, enriched with dressed niches, and a rusticated basement. It is not completely finished, and expended about £25,000. The inside presents many conveniences and beauties, particularly a committee room, thirty-nine by twenty-seven, a library thirty-three feet square, a hall fifty-seven feet by twenty, and a beautiful circular vestibule.

“The Commons House not being thought sufficiently convenient, and the House being desirous at the same time to improve the external appearance of the building, it was determined to make considerable additions to the westward of the old structure. The designs of Mr. Robert Park, architect, being approved, it was begun in August, 1787, and completed in October, 1794, and comprises an extent of building nearly equal to that on the east. The western entrance is under a portico of four Ionic columns, and is attached to the old portico by a circular wall, as on the opposite side; but with the addition of a circular colonnade of the same order and a magnitude as the columns of the portico, twelve feet distance from the wall.

“This colonnade being of considerable extent, gives an appearance of extreme grandeur to the building, but robs it of particular distinguishing beauties, which the plainer screen wall to the east gives to the porticoes. The inside of the addition comprises many conveniences, particularly a suit of committee rooms for determining contested elections before the house, rooms for the housekeeper, sergeant-at-arms, &c. [unnumbered page] and a large hall for chairmen to wait in with their chairs. The whole expenditure of this addition amounted to £25,396.

“On the 27th of February, 1792, between the hours of five and six in the evening, while the house was sitting, a fire broke out in the Commons House, and entirely consumed that noble apartment, but did little other damage. It is conjectured to have taken place by the breaking of one of the flues, which run through the walls to warm the house, and so communicated fire to the timber in the building. Its present construction very nearly resembles the old: it is circular; the other was octangular.

“When this edifice became the property of the governors of the Bank of Ireland, the east and west ends were dissimilarly connected with the centre—a circumstance which must have produced a want of uniformity in the front, unpleasing to the eye of the spectator. This defect has been happily removed, and the connection is now effected by circular screen walls, ornamented with Ionic columns, supporting an entablature similar to that of the portico, and between which are niches for statues, the whole producing a very fine effect. The tympanum of the pediment in the centre of the front is decorated with the royal arms in bold relief, and on its apex stands a figure of Hibernia, with Fidelity on her right hand and Commerce on her left, distinguished by their proper emblems, executed by Mr. E. Smith.

“The noble Corinthian portico that adorns the eastern front of this edifice possesses uncommon beauty, and is seen to great advantage from College-street: the tympanum of the pediment is plain, but on its apex is a statute of Fortitude, with Justice on her right hand and Liberty on her left, distinguished by their appropriate emblems, and executed in a style of lightness and elegance that does credit to the artist already mentioned, by whom they were designed and executed. The architectural incongruity already mentioned is, it must be acknowledge, a defect, but of so little importance as by no means to justify the idea of taking down this beautiful portico, and rebuilding it in the Ionic order.

* * * * * * * * * *

“I stood by its cradle—I followed its hearse.” Often have these few words—Henry Grattan’s exquisitely compressed history of his connexion with the Irish Legislature—floated sadly through my mind. For nearly half a century has my lot been removed far away from the strifes and animosities of my native land. I am not prepared to say, that the blending of the National with the Imperial Legislature was not a measure prudently and skilfully framed and executed for the positive benefit of both islands; and that ultimately its success will be complete, is not yet beyond the bounds of reasonable hope. We are told that half a century of confusion and turmoil, has proven its inutility. Let it not be forgotten, that peaceable, happy and contented Scotland, chafed as long, as furiously, and as hopelessly. Nearly [unnumbered page] forty years after union, the chivalrous irruption of the gallant Highlanders of Charles Edward into the heart of the midland counties, all but snatched the English diadem from the brows of the House of Brunswick. Therefore the voice of the old man still preaches, “Hope on—hope ever.”

The best and fairest hours of my varied life—the warmest blood in my veins—the strongest energies of my heart—have been spent in the service of the crown of the United Kingdom. I have followed the Imperial standard into every quarter of the globe. Ours was a family of soldiers, and most of us have sealed their devotion to their country with their blood. I carried the regimental colours at the first of the victories of Wellington. I the last desperate charge of the Mahratte horse—pierced with uncounted sabre-wounds, fell the eldest-born of our household, and we gave him a soldier’s grave in the hot plain of Assaye. Another sleeps beneath the hard-won rampart of St. Sebastian; and these eyes beheld the loved and honoured forms of my father and his youngest-born, stark and cold, beneath the moonlight on the bloody causeway of Quatre Bras.

Here, after many wanderings, I am anchored at last, in a quiet and peaceful home—a fitting haven for the dark of the storm-tost soldier. There, to the right, beyond that cedar chump, lives my excellent and kindly neighbour ———, a descendent of Sarsfield, and a grandson of a well-known leader of the anti-government party between 1792 and ’98. Half a mile to the left, in yonder bend of the creek, is the hospitable hearth of worthy, whole-souled ———, of a family of the deepest Orange, and himself an enthusiastic native of the “maiden city of Derry.” Happily and kindly do we all live together, each ready with a good-humoured smile at the other’s prejudices. From the verandah of my forest home, I sit and watch the snow-storm, or the breath of summer fluttering the broad bosom of Ontario; and oft-times, in the calm of an August sunset, as the sounds of labour and the prattle of great-grandchildren gradually sink into silence, I look over the stirless waters to yonder distant wood-fringed islands that bound the southern view. And in the soft blue haze of summer’s eve, and in the dimmed eyes of the old man, it needs but little stretch of fancy to call up a solemn but not unpleasing picture of the waves of a peaceful, tranquil death intervening between the calm evening of my life and the bright, far-off islands of Eterniy. Very gently has the Giver of all good dealt with me, in granting the quiet eve to succeed the stormy morn and noon of an eventful existence. Would that all who have passed through as turbulent and varied a career, and such a tumult of opposing prejudices and interests, had been vouchsafed as fair a rest—as peaceful a haven! [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration

[2 blank pages]

MARIA.

Look down, sweet Love! the fairest hour That Summer gives the sleeping Earth Hath hush’d the bird, and lull’d the flower, And still’d the wind’s playful mirth. All beautiful the moonlight streams Thro’ the old forest’s leafy halls, And fitfully soft echo seems To waft the fairies’ sportive calls. Come forth, sweet Love! a thousand things Around thy bower soft incense breathe, And musical each slow wind brings Faint whispers from the glen beneath. The star-lit fount is singing near, The wild brook hums a sleepy tale, And elfin chorus waits the car Of her who lights this haunted vale. Still hush’d, sweet Love! I would not seek To woo thee from one happy dream, If it a kinder voice can speak, If it can bring a dearer theme, One soft “Good night”—no more I ask, If bless’d thy guileless slumber be, Bright is my vigil—sweet my task— To dream of hope—to watch o’er thee. [unnumbered page]

TRANSLATION FROM HORACE.

Bacchum in remotis carmina rupibus

Vidi docentem (credite posteri!)

Nymphasque discentes et aures

Capripedum Satyrorum acutas.

Carm. ii. 19.

The Wine-God teaching his brightest lay

In the lonely rocks I found,

(Believe, ye sons of a future day!)

‘Mid the listening Dryad’s entranc’d array

And the quick-ear’d Satyrs round.

My heart throbs high with a trembling glow

Fresh-caught from thy fountains burning flow,

Lyæus! spare!

With thy thyrsus—emblem of might below,

Spare—oh! spare.

The stormy mirth o the Bacchic train,

The red grape’s flashing spring,

The milky streams through the laughing plain,

The old oaks weeping their honied rain—

Mine—be it mine to sing!

How the crown of thy blessed Love was given

To gleam ‘mid the stars of the midnight heaven,

How the royal Thracian fell,

Of the Theban domes in thy fury riven—

Mine—be it mine to tell!

The Rivers bend at thy dread command,

The Ocean rests spell-bound,

And the poison-snakes in thy Godlike hand

Are twined and braided—a harmless band

To circle thy brigvht locks round,

And Thou—when the Titans scaled the height

Of thy parent heaven in their impious might—

Where wert thou?

A Lion—borne through the yielding fight

With death on thy shaggy brow? [unnumbered page]

Tho’ to lead the dance and the mirth-crown’d hours

Be thine unwarlike fame,

Since thy deeds by thy father’s shaken towers

Red Battle’s splendors—soft Peace’s flowers,

Light up thy glorious name!

And the Dog of Hell, with a cowering eye

And a peaceful heart, from his hair drew nigh

Thy God-like step to greet,

And lick’d, as thy graceful form swept by,

The dust of thy heavenly feet.

SONG OF THE ANGLO-CANADIAN.

There’s a land—they call it “The land of the Free,” ‘Tis our far-off Island home; Her fame is wide as her subject-sea, And pure as snow-white foam. But we’ve left the graves where our kindred sleeps— The towers that our fathers raised, The ancient rivers—the mountain steeps, The fares where our God we praised. We’ve left thee, thou land of the lofty crest! We have come o’er the sounding sea; We have made our home in the youthful West, But our hearts are still with thee. And we thank our God that the fair young hand, That ruled us with gentle sway In the ancient homes of our Father-land, Is over us still to-day. Oh we love the land where our lot is cast— ‘Tis a land that is fair and free; But it springs not from thoughts of the glorious past, Like the love that we bear to thee. [unnumbered page]

A FAREWELL.

Shatter’d hopes of idle youth!

Golden veils of mournful truth,

Shapes of Morn’s ecstatic reign,

Phantoms of the dreaming brain,

Shadowy children of the Past,

Heart-enchanters to the last!

Now at length your world is over,

Now the grave your forms may cover,

For the veil is rent asunder,

And the cold stern Truth is under.

* * * * *

Ye were mine too long, too long,

(So I sing my parting song),

Happy day and starry night,

Have I revell’d in your light,

And my World was all enchanted,

While the path of Morn was haunted

By the shapes of golden dreams,

By the wings of glorious beams,

By the breath of happy voices,

As when Heaven with Earth rejoices.

* * * * *

So farewell! fair dreams—we sever,

With this parting word—for ever!

With one sigh for wither’d flowers,

With one thought on pleasant hours,

When the rainbow spam’d the fountain,

When the blue mist wrapp’d the mountain,

When the spring winds knew a song

Which they sang the bright day long,

When each star upon its brow

Wore a glory—not as now!

Young Romance—thy dream is over,

And we part, the lov’d—the lover—

Tho’ the weak heart turn to linger

O’er the thoughts the Past may bring her,

Firmer yet the lip will tell

We are parted—so—farewell! [unnumbered page]

A CHAPTER ON CHOPPING.