THE FOREST OF BOURG-MARIE

BY

S. FRANCES HARRISON

TORONTO

GEORGE N. MORANG

1898

THE FOREST OF BOURG-MARIE

CHAPTER I.

ALL ABOUT MAGLOIRE.

‘A man was famous according as he had lifted up axes upon the thick trees.’

BORDERING the mighty river of the Yamachiche there are three notable forests, dark, uncleared, untrodden, and unfrequented by man, lofty as Atlas, lonely as Lethe, sombre as Hades. In their Plutonian shades stalk spectral shapes of trapper and voyageur, Algonquin and Iroquois, Breton and Highlander, Saxon and Celt. Through their inmost recesses range spirits who revisit, say the imaginative peasantry, the scene of their former labours, wood-cutting, tree-felling, bark-tapping, bait-setting—a race of strange and sturdy men, afraid of nothing except shadows, strongly and deeply religious, drinkers of the open air, silent, inscrutable, wary. The three [Page 1] forests are, respectively, the Forest of Lafontaine, the Forest of Fournier, and the Forest of Bourg-Marie, and upon their outskirts dwell the descendants of the hardy trappers, the dashing voyageurs, the slim, refined Frenchmen from the Breton coast, and mixed British—phlegmatic Scotch, impulsive Irish, grotesque Welsh—with an occasional Teutonic or Hungarian contribution.

The Forest of Bourg-Marie is the darkest, the deepest, the most impenetrable, the most forbidding of the three. The stars of spring that light up other woods seem here rarely to pierce through the cold, hard ground to the sun: the sun itself seldom penetrates the thick branches of fir and pine and hemlock. The tints of autumn that beautify the death of the year in other places are absent from its partially-cleared fringe of pine-tasselled ground; there seems no colour, no motion, no warmth anywhere. Fitting soil for fable and legend, for the tale of Dead Man’s Tree, for the livelier story of ill-fated Rose Latulippe, for countless minor myths that the old women and the old men, even the young men and maidens, have at their fingers’ ends, and which once started, they will recount all day and half the night for the interested traveller. Fitting haunt for the famous beast or bogey known as the Loup-Garoux, a thing so hateful, so terrible, that for all the countryside the name is fraught with curious yet awful fear. Fitting habitation—the entire valley—for bear and [Page 2] snake and salmon and deer—for all things that court the solitude and exclusion of the almost primeval, the undisturbed, the unfrequented.

The Forest of Bourg-Marie is the darkest, the deepest, the most impenetrable, the most forbidding of the three. The stars of spring that light up other woods seem here rarely to pierce through the cold, hard ground to the sun: the sun itself seldom penetrates the thick branches of fir and pine and hemlock. The tints of autumn that beautify the death of the year in other places are absent from its partially-cleared fringe of pine-tasselled ground; there seems no colour, no motion, no warmth anywhere. Fitting soil for fable and legend, for the tale of Dead Man’s Tree, for the livelier story of ill-fated Rose Latulippe, for countless minor myths that the old women and the old men, even the young men and maidens, have at their fingers’ ends, and which once started, they will recount all day and half the night for the interested traveller. Fitting haunt for the famous beast or bogey known as the Loup-Garoux, a thing so hateful, so terrible, that for all the countryside the name is fraught with curious yet awful fear. Fitting habitation—the entire valley—for bear and [Page 2] snake and salmon and deer—for all things that court the solitude and exclusion of the almost primeval, the undisturbed, the unfrequented.

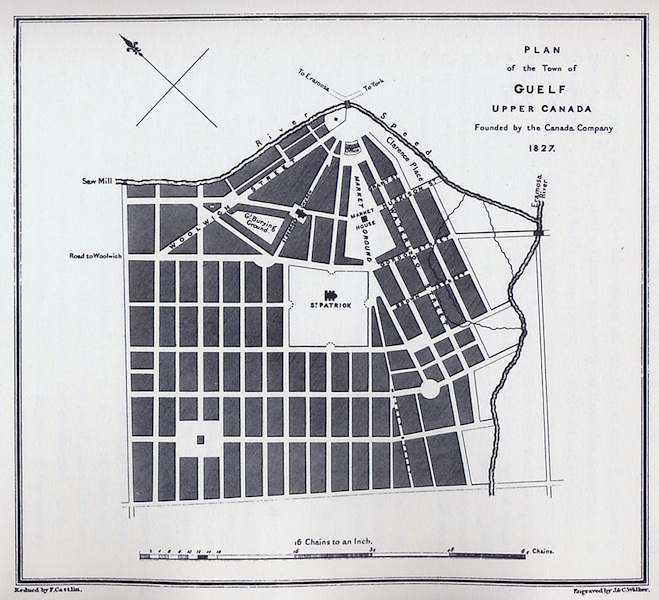

Mikel Caron, forest-ranger for the County of Yamachiche, was, in all probability, the only man who, within the memory of those living, had thoroughly explored these haunted arches, and pressed towards the crescent of light that bounded them on the other side. This Mikel Caron, unusually tall, painfully thin, with furrowed brown face, ferret’s eyes, and slouching gait, is the walking observatory, the weather-prophet of his county. He knows every tree by name and by sight on the outskirts and well into the middle of the three great forests. He knows every sign of peeling bark, of shifting soil, of running or drying sap, of outgoing bird, of ingoing skunk and squirrel, of fading or budding flower, of unset blossom, of hardening fruit, of ice-scratched boulder, of drifting leaf, of sodden hoof-mark, of lofty nest, of lowly burrow. This Mikel Caron is the great-grandson of a son of Messire Jules-Gaspard-Noël-Ovide Delaunay-Colombière Caron, who held at one time the Seigniory of Bourg-Marie, extending along the western bank of the Yamachiche for 900 arpents—a fief granted, according to the mouldy and rat-gnawed parchment of the ‘Actes du Foy et Hommage,’ to its first holder in the year 1668. The fief has slowly but surely dwindled, till, in the hands of Mikel Caron, [Page 3] shorn of his long array of high-sounding names as well as of glebe and wood and river, it is represented chiefly by the immense Forest of Bourg-Marie.

This fact rarely troubled Mikel. Of what use was land to an old and childless man like himself, and such land—acres of bog, acres of forest, miles of river, ranges of mountains!

If Magloire had come back, then—but Magloire would never come back. That Eldorado, the States, had attracted him. See how the quick lad early learns to hate the inconceivable dulness, slowness, inclemency, roughness, misery of the life! From his tenth year he had actually dared to array his little person and his childish opinions against the curé, who lived at Yamachiche, his uncle, and the rustic minds of his native countryside. Mikel had helped too—Mikel who had slapped Magloire on the back, and cried that he would be a great man some day and go up to Quebec and speak in the Council; Mikel, who now would give all his ancient lineage and his right to Plutonian Bourg-Marie for a glimpse of Magloire’s sleek little black head and the sound of his sharp falsetto voice. No; it was certain Magloire would never come back. So Mikel’s philosophy—learnt from Nature, from brooding twilight glooms, from diamonded midnight vigils spent in eluding heavy-breathing bear or sly russet fox, from hot, sleepy noons in a canoe on the sparkling river, from cool, dewy dawns in the lumbermen’s [Page 4] camp or shanty; such wisdom, borrowed from furred and plumed, erect, creeping and prowling creatures, and from stone and sap and soil and stump as well—upheld him and comforted him in his lonely life. From the eagle he got his easy soaring to thoughts as to heights the curé himself could hardly follow; from the bear his indomitable dogged pluck, which neither Arctic blasts nor torrid waves ever affected; from fish and snake and small birds the habits of attention, minute and accurate observation; the alert eye, the sensitive ear, the rapid motion. To go without food for four or five days, and without drink for three, content with moistening his lips with snow or sucking occasional icicles; to sleep in a hole in the snow, with more snow for blankets and quilt; to face blinding storms and buffeting winds, hail, rain and frost, wild beasts, murderous half-breeds, suspicious Indians—all this was easy to Mikel, because his early training had fitted him to endure, and even to enjoy, what he never dreamed of designating as hardship. In this life had the great-grandson of the son of Jules-Gaspard-Noël-Ovide Delaunay-Columbière Caron grown old.

And there were two seasons in that lonely land when Mikel, and with him all other old men, felt the pressure of years most bitterly. One was when the leaves of sudden spring made green waves in the valley, flooding with verdure, sunshine, and [Page 5] melody the dismal banks of the half-frozen river, when birds returned, and cascades leapt, and the waxen pyrola gleamed at the foot of the tallest tree. Again, when the leaves of brilliant autumn have floated to the ground, floated, shrivelled, and been caught up in a whirlwind of fire, which consumes their beautiful souls and consigns them again to the dry dust by the wayside. Not that Mikel was troubled by poetic apprehensions and fanciful analogies, the comparing of human life and perishing mortality to withered leaf and flying dust, but that his sense of coming impotence, perhaps dependence on others, inability to cope with Joncas* and Laurière, powerlessness in the face of the axe, the saw, the gun, the knife, fear when confronted with slow-moving bear of lithe brown fox, impressed him deeply with aversion of the approaching winter. Stoical, like the Russian, the old-time Greek, the Highlander, the well-born Englishman, Mikel had more than a passing trace of the voluptuous French, nursed, not in hardy Basque province, or by the shore of sea-washed Normandy, but in the rich, plentiful, vine-clad, corn-gilded inland meadows and valleys of the Haut Champagne.

It was on an autumn evening, about six o’clock, and very dark indeed for even a dark October, that old Mikel, returning from an extended examination of more than twenty-five bear-traps, set in the obscure [Page 6] shadow of Bourg-Marie, found Nicolas** Laurière awaiting him—Nicolas Laurière, straight, slim, pale, young, with broad shoulders, brown eyes, and a handsome moustache; Nicolas Laurière, twenty-five, only a stripling, yet the bravest, most intrepid, and most skilful of all the Yamachiche trappers.

Mikel, hastening moodily home, almost walked into Laurière, as the latter stood leaning against the low fence surrounding Mikel’s house and clearing.

‘It is I—Laurière,’ said the younger man, moving aside and opening the little gate for Mikel, that the latter, weighed down as he was by tools and pieces of wood, might pass through the more easily. ‘It grows cold, dark, and at home I am not wanted. I can help you perhaps, Mikel, you who work always, even when other men sleep.’

Mikel was displeased, and swung the gate to behind him, forgetting the friendly purpose of his visitor for a moment; then, with an effort to sink the touchy feeling in one less selfish, opened it again and motioned to Laurière to enter.

‘There is work—yes, there is work, if you are so ready for it. Certainly, one can always find work near Bourg-Marie. So enter; find it; do your will. There is supper enough for two.’

Laurière silently followed Caron into the kitchen, already illuminated by the glowing logs, that revealed [Page 7] a grateful warmth and radiance when the older man opened the end door of the long black stove.

Mikel was unmistakably sullen. He grumbled at the bad wick of his one lamp. He shot inquiring yet moody glances at Laurière.

‘Say, you,’ he said, getting out some cracked cups and plates, bread, tobacco, a dish of cold beans and cabbage, and some whisky, ‘why do you come to-night—you, Laurière? Is there news?’

Laurière sat down and warmed his hands well before he spoke.

‘Well,’ he said at length, ‘there is—a little, a very little—in the village.’

There was an immediate change in the old man which might have manifested itself in a more vulgar nature by the smashing of delf or other clumsy self-betrayal. In Mikel, however, such was his power of self-control and stoical command or suppression of the emotions, that this change was confined to a lighting up of the wrinkled visage, and corresponding improvement in his voice. He grew almost gracious.

‘I thought you would not come for nothing. There is nothing else that need bring you, eh, Laurière?’

The younger man laughed deprecatingly. He would have to humour old Caron.

‘No, no,’ he said; and very politely he half rose from his chair.

Mikel was a recognised person in his neighbourhood, [Page 8] and it was well known that he was in truth a seigneur, and, as such, worthy of the respect and courtesy of the valley.

‘Well, now,’ said Mikel, sitting down in front of the stove and regarding his visitor shrewdly, ‘what is this news? Is it, now, of bears, or of foxes, or of squirrels? Is it, now, of smuggled spirits, or weather omens, or dances up at Madame Delorme’s? Ah-h-h, you will all be found out some day—smuggling, jesting, dancing, drinking! Keep cool and quiet, like me—like me! Come, the news!’

‘How well he acted!’ thought Laurière admiringly. ‘With his heart beating as if it would burst beneath that shaggy fur waistcoat, and his yellow teeth anxiously biting his blackened lips—old fox, old man-of-the-woods, old bird of prey, still wary, cautious, controlled!’ But Laurière was made of much the same stuff—Mikel’s pupil he called himself.

‘I thought,’ said Laurière timidly, slowly, and raising his eyes deferentially to Caron’s inquiring, yet not over-eager face, ‘that you would guess the news, for it is of something better than bears, or dogs, or foxes; of something nearer than Mother Delorme and René the smuggler. It is news of Magloire.’

Mikel lowered his eyes, but did not move. Laurière, divining he had permission to speak, continued in a more natural and sprightly tone, warming with his subject.

‘Yes, of Magloire. There are those who have [Page 9] seen him, spoken with him, over where he is gone, in these States. They say he has grown very tall—taller than I am—as tall as Jules Blondeau, who married the sister of Joncas; he who caught the fifty bears last winter.’

Little need to remind Mikel of this fact.

‘I remember,’ he said with unmoved face. ‘Speak on—of Magloire. He has been seen and spoken with? By whom? This Blondeau?’

‘No,’ said Laurière, always carefully, but more familiarly than at first. ‘By two men who left Bourg-Marie. It is four years since they will have left and gone to Milwaukee.’ He accented the final syllable. ‘These men, they were the sons of la veuve Péron. The brothers, Louis and Jack, they were in Milwaukee, without work, and without anything to eat. They were saying how much better it was in Bourg-Marie, how the potatoes, and beans, and whisky were there all the year round, and how kind the neighbours always were to one another; and they spoke of many things as we did them here, and of Joncas, and of the Mother Péron, Madame Marie-Louise, and the church, and of you. Oh yes, it was of you they spoke often, wondering what the winter was going to be like that year, and how you could tell them in a minute if you were only there by just seeing a bird wheel across the sky, or the bark and moss on the outside of the great logs of wood going on the carts to rich men’s houses.’ [Page 10]

‘Quiet, thou!’ growled Mikel impatiently. ‘Speak on, but of Magloire, and not of these, thy friends—fools! Of Magloire, speak!’

‘Well, Louis and Jack, they will have been hungry for a long time, and sorry they ever left Bourg-Marie. The people of that town are all English, and speak only their own tongue; and it is all strange to these men, who are called “Canuck” and “Frenchy.” This would displease anyone but Louis and Jack. Everyone knows they do not like names at all, and this day that they were most tired and hungry, all at once, driving past them in a sleigh of the handsomest, with fine dashing horses, they heard the man who was driving them singing aloud one of our own songs, “C’est François Marcotte.”’

Undeniably excited, and worked upon by Laurière’s perverse slowness of recital and delay in coming to the point, Mikel allowed an exclamation to escape his quivering lips.

‘That was he! That was Magloire?’

Laurière inclined his head.

‘It was himself—Magloire. But they—Louis and Jack—did not know it was he. See, then, how long since he was at home, here, with you, amongst his friends. No, they could not tell that it was Magloire. But when they heard the voice and the song, they knew it was someone from the county, or at least from here, from Canada, and they waited, day [Page 11] after day, till they saw him again, and then they stopped him. It was Magloire Caron, of Bourg-Marie, and your grandson. He was tall, as I have said, healthy, well-dressed, and amiable; gave his name at once, had forgotten nothing, nor—nor anybody, and promised to do all he could for Louis and Jack. But that was four years ago.’ Laurière feeling himself drawing near the end of his simple narrative, stole a look at Mikel, and concluded in a tone which would have rung false to anyone less absorbed than the old and often disappointed trapper, so laconic was the inflection. ‘He has prospered, for sure, Magloire.’

‘Prospered! Magloire! You are certain it was himself? These are true men, this Louis and Jack? Prospered, and he has never written!—prospered, and I have had to toil and drudge!—prospered, and not even remembered the good father, and the church of the holy St. Anne!’ The old man was entirely off his guard now, and clutched at his waistcoat with trembling hands. ‘Driving, you say—driving—his own horses—Magloire! Well, it is as it should be, were he only dutiful enough to remember me and—and Father Labelle. Well, but it is a wonderful country, that States.’

Between wrath and importunity, delight and wild reproach, jealousy and parental affection, Mikel was beside himself and ill-prepared for Laurière’s next statement. The younger man, playing nervously [Page 12] with his knitted tuque between his hands, had no idea of sparing his co-worker and patron, however much he might admire and respect him. The instinct of the hunter, the trapper, pursued him even more than he was aware.

‘Well,’ he said, in that deliberate, laconic half-voice which should have warned the older man—well, he has prospered, ouai***—yes, much, but not so much as that. Those horses, they were not his own, not Magloire’s. No; they belonged to his master, to a—gentleman. Magloire, he was the driver, the coachman, when Louis and Jack Péron see him there in Milwaukee—the coachman. Ah ouai, he has prospered, that one; but you will recollect we always said he would prosper. Bien ouai, that is all about Magloire.’

Laurière was no coward; his life had surely proved his prowess. But in face of Mikel Caron, his elder and superior, torn and distorted, rent asunder by stern, awful and conflicting pains, he assuredly quailed, although he sat outwardly quiet in his chair by the big black stove, for Mikel was horribly angry, embittered, disappointed. Magloire, his grandson, heir of the Columbière Carons of Bourg-Marie, a coachman in the employ of some well-to-do tradesman or pork-packer of the West—Magloire, waiting on other men, instead of having other men wait on him, servile, dependent, debased. [Page 13]

Laurière rose to go.

‘If he were to come back—back to Bourg-Marie—you would see him, would you not?’

Mikel drew a deep breath.

‘Do they say that he will come back?’

‘Louis and Jack Péron? Well—yes. They have heard that he is likely to come back some day.’

‘Why should he do so?’ said old Mikel stolidly. His transport of rage over, he disdained expressing emotion or even interest. ‘There are no carriages here. He would be nobody here, not even a coachman, in Bourg-Marie.’

‘That is true,’ said Laurière politely; ‘and now I will bid you good-evening; and when I see these Pérons—they are with their mother for a holiday—I will tell them I have seen you, and that you know all about Magloire.’

‘Bien ouai! All about Magloire!’

Mikel was quite himself—cold, collected, a trifle satirical, and very authoritative. Laurière had reached the door, when the older man called him back.

‘Stop, Nicolas Laurière!’ he said. ‘You are going without your supper.’

Laurière opened his hands, and gave a slight shrug of the shoulders; but Mikel insisted, and the two men sat down together and supped in almost total silence, for Laurière, not very lively among men of his own age, became abnormally taciturn [Page 14] and reticent in the presence of the leathern-visaged, crusty, aristocratic and venerable Caron. A magnate is another being, and one easier to meet; but an equal who is yet more than an equal, for he knows your business better than you know it yourself, is sometimes difficult to encounter.

Laurière stayed only to eat his share of the meal, and left. It was about eight o’clock, and a fine web of moonbeams began to spread over the dark autumnal skies. Both men scanned the night.

‘No bear to-night,’ said Caron.

‘Well, no,’ replied Laurière. ‘Wait awhile; there will come plenty, eh?’

The owner of Bourg-Marie nodded, and shut the door. In a few moments Laurière was out of sight and hearing, and the most profound silence prevailed. [Page 15]

CHAPTER II.

MAGLOIRE HIMSELF.

‘The simple inherit folly.’

THE little narrative which the young man Nicolas Laurière had told old Caron was quite true. He himself rather envied Magloire. Two or three times he had been on the point of relinquishing the plain fare, the hard work, the inclement climate, to try for a living somewhere else. He was not the enthusiast Mikel was. He and Joncas were trappers because their fathers had been trappers—they had to be; there was nothing else for them to be. Yes, he quite envied Magloire, though he understood fully that whereas at Bourg-Marie one was one’s own master, that would be all very different in another place. About the same age as Magloire, at the time of the latter’s disappearance the same temptations attracted him, for tidings of the great world outside were slowly colouring the life and minds of his native countryside. Here and there [Page 16] an ambitious maiden of eighteen, who found her way up to the large English-speaking towns and became a waitress, a nursemaid, a maid-of-all-work, would return at rare intervals and pour into the ears of her family tales of the opulence, the size, and the population of Three Rivers or St. John’s.* Sometimes a paper would arrive bearing in rough-marked edges witness of a young stripling from a farm or ‘shanty’ who had found friends and fortune in the Upper Province or in the States, and this paper would be handed about from house to house as the rarest of literary treasures. And whenever this kind of thing overtook Laurière he would grow restive and moody, walk away from the company, and, staring blankly at the flat dull landscape, go for a walk of ten miles to Mad Dog Creek, and return hungry and cured.

On this cold night Nicolas was discontented, although no distinctions of caste troubled him. He strode away from the ranger’s little dwelling along the hard gray rutted road at a great pace. On either side of him stretched the forest, dark, inscrutable, yet not forbidding to one who so often, both with Caron and by himself, had threaded the edge of its cavernous recesses. The road lay perfectly straight for a mile, then turned sharply round, disclosing the sullen river, not yet frozen, but soon to be, so black and opaque it lay beneath the faintly glimmering stars. A dog appeared, running swiftly. [Page 17]

It approached Laurière, smelt him, seemed to approve, wagged his tail, and returned whence he came, followed by the trapper. In a few moments the red light of one window appeared sharply in the gloom, and Nicolas, vaulting over the low snake fence, rapped upon the door of the cabin belonging to the widow Péron, the mother of Louis and Jack, the travellers who were now home for a holiday from the high pressure and other modern disabilities of life in Milwaukee. The door was opened by Pacifique, the third and youngest son. He had never left his mother nor his native valley, and bore with Nicolas a striking contrast to the other three young men who were lounging in the small kitchen. The shortest of these was Jack Péron, fat, olive-skinned almost to lividness, with podgy hands and a laughing mouth. The next to him was his brother Louis, thinner, slightly gaunt and weird, with suggestion of the traditional stage Lucifer in his pointed eyebrows, beard, and chin. The tallest of the three, however, Magloire Caron himself, exceeded his companions in appointments, dress, and general bearing, as much as in height. He was, indeed, unusually and exceptionally tall. His hair, of the harsh jet-black stiff kind so frequently found among his countrymen, was parted in the middle, and, after being drawn away to either side in two well-marked horns, was plastered down everywhere else with the newest thing in pomatum, a preparation of castor [Page 18] oil, bay-rum, and attar of roses. His costume was an English tweed of not unprepossessing pattern, considered alongside the preposterous gray and claret check that Louis and Jack had both chosen as best calculated to display their knowledge of correct fashion, and to please their devoted mother. His cravat (Magloire’s) was of pale pink linen, worn over a striped navy-blue and white cotton shirt. His jewellery was very much en evidence, and a silk handkerchief, in which purple figured on a saffron ground, completed the iridescent nature of his apparel. And although this quasi-picturesque garb did not offend so keenly in his case as it would have done in that of a more purely prosaic type, still, on comparing its pretentious vulgarity with the admirably careless and characteristic appearance of Laurière, it seemed a pity that his magnificent proportions, his glistening teeth, his night-black hair, and his sombre but healthful complexion, were lost, if not indeed made ridiculous, by his affectation of a foreign style. In the sombrero and cloak of the Mexican, in the jacket and cap of the Spaniard, in the ample linen and glowing sash of the Greek, or even in the high-crowned hat wound round by a scarlet ribbon, the flannel shirt and earrings of his own despised countrymen, he had been handsome. In his imported English cheviot, his cheap jewellery, and his ill-assorted colours, he narrowly escaped being absurd. Yet he was very much admired. Louis and Jack, [Page 19] who had done well in Milwaukee, but not as well as Magloire himself, admired him intensely, and, it might be added, despairingly. In fact, after that meeting on the main street, when the vision of their old friend and playmate flashed past them, clothed in black bearskins and importance, the brothers made an idol of him, and formed themselves upon him in every respect.

Pacifique admired him. So tall, and Pacifique was short; so regular-featured, and Pacifique was crooked; so self-possessed and graceful, and Pacifique was stunted, crippled, worn, and shy. The veuve Péron admired him. Had he not been the means of setting up her own boys? and, although they did not appear to have brought home very much ready-money, still they were beautifully dressed, and altogether different from the young men in the village, and spoke about an account in the savings-bank. What more could the widow ask? Admire Magloire? Bien ouai—for a splendid fellow!

Nicolas Laurière admired him perhaps most of all. As Magloire was, so he, Laurière, should be some day. He had no grandfather with medieval notions to threaten his peace or interfere with his projects. He would leave this place, come what might. And just as he reached this decision—for the hundredth time—Magloire, seeing him enter, beckoned him to his side by the fire, around which the little circle was [Page 20] gathered. His manner was nonchalant, yet assertive, and impressed Laurière more than ever with its novelty and importance.

‘Say, then, you,’ he said, ‘Nicolas Lauière,’ relapsing into his native Franco-Canadian, for he spoke English all the time when in Milwaukee, ‘have you seen the grandfather?’

Laurière recounted in the same tongue the outlines of the conversation. Delicacy for, and admiration of, Magloire prevented him from disclosing the whole state of the old man’s feelings. But Magloire was quick, and able to see through a simple type like Laurière at once. He laughed, and his laugh was not altogether pleasant to hear. He crossed his long legs in evident comfort before the widow’s fire, and taking from his pocket a penknife, commenced to cut and clean his nails. He had been reminded of a little dirt in them by the sight of the aggregate contained in those of Laurière. ‘Speak English,’ he said to the latter.

‘We don’t hear much French out West, do we, Jack? So my grandfather knows I was a coachman that time. Well, I tell him myself yet as well as you tell him for me. He was angry, eh?’

Laurière nodded. He watched his friend clean, pare, file, and polish his finger-nails without it ever occurring to him similarly to treat his own. A law unto himself is every man in Bourg-Marie.

‘Why,’ said Magloire, finishing his nail-toilet, and [Page 21] beginning on a cigar, which he produced with a grand air from an inner mysterious pocket, and lit with a perfumed match, ‘you are all behind here, and that is the truth. Me and other fellows that goes to the States, we see life, we see the world, we grow, we improve, we watch, we find out how things are done. We do not care to stop in Bourg-Marie all our lives, nor even in Three Rivers. Ah!—bah! that is a small place, that Three Rivers, anyhow!’

Rank heresy in the ears of Widow Péron and Nicolas Laurière; yet, only half comprehending the foreign tongue, they listen respectfully, timidly. Pacifique squats by the corner of the fireplace. He does not understand the English at all, but is thinking what present he can make Magloire when he leaves them. Snowshoes—raquettes?—no; a carved pipe?—no, that young gentleman buys cigars. Well, it will come into his head, his stupid head, presently.

‘Me and other fellows,’ continues Magloire, conscious of his admiring audience, ‘well, such as Jack and Louis. And there was one Amable Blondeau—e cousin—’

‘Ah, ouai!’ exclaimed the widow hurriedly; ‘le cousin de notre Blondeau.’

She stopped apologetically, and Magloire condescendingly went on:

‘The cousin of this Blondeau the trapper. Well we have learnt a great deal since we go to the States. [Page 22] There every man is free! You understand that. There is no man that is not free. That is, he can do, he can go, just as he likes, just where he likes. That is a fine country, and there are many places to go to. There is lots of fun. And the bizness—ah! that is the place for the bizness.’

‘What you do all de time?’ asked Laurière uneasily. ‘Dhrive all de time. Well—sure, I like dat too well, for a little. I get cold—me. I—custom—walk—much—all de time.’

Magloire laughed again.

‘Cold!—when you are all dressed in fur! Get out, you, Laurière! Ask Louis and Jack if they ever seen me cold, eh?—nose red, eyes water—no, no. I have nice coat—real bear—like the ones you shoot yourself. Look here, Nicolas Laurière, how old are you? As old as I am almost. Well, I sit on top a handsome sleigh; I wear black bearskin. I am a member of two societies—yes, certain. I go to the races. I have fine time. You—you walk about day after day; you watch till you sleep, night after night; you shoot or you trap plenty fine bear. What do you with him, eh?’

Laurière was silent. The picture was too true.

‘Well, I tell you what you do: You sell them to the traders, to the fur-merchants en haut. They travel up, up, and up, change hands, cross the frontier, till they are on my back, keeping me warm—so-so.’ [Page 23]

‘You make much money?’ queried Laurière.

‘What do you think?’ I wear good suit, handsome overcoat; I have a watch and two rings. The watch—well, that is not finished to be paid for yet. There is a way they have there in these States that I will tell you. The stores, they have each a man who is honest, and wants much something to do. So they give him a large box, full of watches, or books, or images, or perhaps coats and furs, and they tell him to take this box to every house and to every person on certain streets, and to get them to promise to buy one watch, or one book, or one image. I was one of these men when I first got work in Milwaukee—yes, sir, I was with a picture-store, and carried round large painting—so—all framed in gold, like those you have seen in the church at the side of the altar.’

Laurière and the brothers Péron looked at one another in dismay, but admiration. The widow had stopped knitting, and moved her lips from time to time in speechless ecstasy. Pacifique was still hunting in his clouded mind for a suitable present for Magloire.

‘So I know all about that kind of bizness,’ continued the latter. ‘Yes, these men they leave the watch or book at your house, if you will pay a little of the price, and then they call again whenever you like for the rest. That is easy and nice all round.’ [Page 24]

‘When you have de money!’ said the fat Péron, who thought this very clever, and began to laugh.

‘Well,’ said Laurière cautiously, ‘I suppose you will be for seeing Mikel as soon as you can. He will be away soon—two week, three week. When will you go?’

But Magloire was not uneasy.

‘Oh! Well, there, you, Nicolas Laurière, you are afraid of my grandfather. Yes, yes, I see, I understand, you are all afraid of him—the old fox, the old man-of-the-woods!’

Laurière did not protest. His race, though garrulous, noisy, and eager in towns, is quieter, more self-contained, more absolutely truthful in the country.

‘Then you will go see Joncas?’

‘My uncle?’ said Magloire. ‘I will see about him. I think he should come and see me first. That is the way we do it in these States.’

‘And the whole of the village,’ continued Laurière. ‘Everyone glad to see you back, Magloire—sure. Rich man—in bizness—so tall, so straight, so handsome.’

His admiration was genuine, and Magloire laid his hand for a second lightly on the other’s shoulder, as he mentally considered the various aspects of his home-coming.

‘Will you go with me to see old Mikel again?’ he asked. [Page 25]

Laurière shook his head.

‘Mikel—he not fond of me. Well, he is old man; soon he hunt and catch bears no more. I, all my life yet to catch him. Well, I can’t help dat. Dat is right, dat is naturelle.’

‘All your life before you yet, and you’re going to waste it in these woods going after bears! Look now, Nicolas Laurière’—and seductively Magloire’s arm stole around the latter’s neck—‘you don’t know what you say. Look at me, and Jack and Louis Péron! We are going back to Milwaukee in a little while—few days. See! You come with us. Eh! Make rich man of you, marry you to pretty American girl, go to the races with me, learn to speak fine English, wear fine new clothes. Well, now, there’s a chance for you, Nicolas Laurière.’

The circle had broken up by this time, the widow being engaged in building up the fire for the night, and the three brothers talking quietly in French apart from Magloire, although still about him and his varied accomplishments.

Now that a chance seemed to offer itself, Laurière felt peculiarly embarrassed. Unaccustomed to any introspection or analysis of the emotions, he did not know that what filled him with hesitation was the fact that he was being tempted to forfeit his nationality and forego his country. Too ignorant to estimate accurately the correct and actual status of Magloire as an American citizen or as an English-born [Page 26] subject of Franco-Canadian descent, he yet experienced something which, subtly, but stupidly, seemed to confuse and cloud his power of will, to bias his preferences. He had longed passionately to go until Magloire had asked him, and then a something struck at his heart and his mental vision so that he could not place, nor could he answer even at random its solemn questionings.

He grew sheepish, shuffled his feet, picked at the tassel of the tuque, and faltered in his reply.

‘Well, I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I have ver’ little money to take me to dat place. I would—oh, I don’t see how I could go. There is work here, and Mikel and Joncas cannot do it all. There was ninety bear killed last year—Mikel and Joncas. Well, when old bear come out and smell around, they will want me too. No, I don’t know. I will see. You are ver’ good. Well, Magloire, I will see.’

Magloire was all fire and attention.

‘Ninety bears killed in one season! That was pretty good work, wasn’t it? Say, where are those skins? Do you know?’

‘The skins? Well, Mikel; he will know. Yes, Mikel; he send them to the Government. I don’t know. But, ninety; dat was not many bear. One man alone year before dat, he kill fifty by himself.’

Magloire whistled.

‘I guess that isn’t so bad if he got the money [Page 27] for the skins. How much does one skin get in Quebec?’

Laurière scarcely understood him. He did not know the value of fur in the least.

‘I don’t know,’ he said stupidly. ‘But Mikel, he know. Ask him when you go see him.’

Magloire regarded Laurière thoughtfully.

‘I will,’ he said, ‘and I will go to-morrow.’ He stood in the middle of the kitchen, the others all regarding him with latent awe and much affection as his handsome face broke into a good-humoured smile, and the firelight travelled over his highly-glazed linen and gaudy jewellery. ‘I have only a little while to stay, perhaps, and I must see my grandfather—eh? Will he be surprised, think you, at the little Magloire grown so tall, and wearing fine clothes and a watch?’ And he swung it aloft as he spoke. ‘Then I will go to the village, and make some presents to the people. To you, Louis and Jack, I give nothing, since we are arrived together. To you, Madame Marie-Louise Péron, I will give—well, you shall see. Perhaps a picture of the Virgin in a car drawn by angels, roses at her feet, framed in gold—bien, madame, you can hang it over the fire. To you, Nicolas Laurière, a little book of the views of Milwaukee, and a pair of studs. Here, stay! look! these very ones—on the condition that when I go back, you shall go with me. And to my grandfather, why, a picture like yours, madame. And so [Page 28] the return of Magloire to his native village will not be altogether an empty-handed one.’

With that the young man clapped Laurière heartily on the back, and wished him good-night, for Nicolas had three miles yet to walk home, and was about leaving in great trouble and perplexity of mind.

Had Magloire forgotten anybody in his list of expectant and delighted acquaintances?

Only Pacifique. [Page 29]

CHAPTER III.

MR. MURRAY CARSON.

‘A foolish son is the calamity of his father.’

MAGLOIRE, being accommodated by the widow Péron with a paillasse, had chosen to remain at her house until he had seen his grandfather. The prospect of the interview did not trouble him in the least, and he set forth, clad in his irreproachable tweeds, swinging a cane, whistling, not a habitant song, minor and true and tender, but the vulgar refrain of a chorus he had heard in a Milwaukee-oyster bar, where a female orchestra enlivened the tedium of the proceedings.

Had he had keener susceptibilities, or, in fact, any susceptibilities at all, he would have felt dimly that this refrain ill-suited the primeval majesty and beauty of the solitude of Bourg-Marie. The hour was ten. A warm October sun caught the rich colours of the still leafy trees, and threw strange glories around on road, and stump, and stone. [Page 30] Magloire, however, thought it all intensely lonely and gloomy. The continual contemplation of Nature drives some men to commit crimes; of others it makes poets and gentle thinkers. Magloire belonged to the first class. Nature could never do anything for him. So he walked along quickly, regretting the lively streets of Milwaukee, the oyster-saloons, the election carts, the polling-booths, the gay windows of the harness shops, the hotel steps crowded with drovers—men of all kinds smoking, chewing; the beautiful young ladies, to marry one of whom he aspired in his secret heart; the girls who sold flowers—tubs of hothouse roses and marguerites at the corners—and who were good enough to wink at and buy from; the music-hall with the half-moon of gas-lamps over the entrance, like false gigantic pearls on the forehead of an abandoned beauty.

All these things were in his mind as he quickly made the two miles between his grandfather’s cabin and that of Madame Péron. A slight beating of the heart would not be set aside or controlled as he approached the gate, and as he walked up the little path, and knocked at the one red door, he recognised the fact that, spite of previous unbroken courage and confidence in himself, he was horribly nervous. His hand shook, and his knees almost gave way.

‘It is nine years,’ he said to himself. ‘It is a long time. Will he know me?’ He brought forth an embroidered card-case from an outer pocket of [Page 31] his light overcoat, and drew from it a card, which read:

MR. MURRAY CARSON,

Hallam House.

Expert in Horseflesh.

And this he held in his hand, which, since he had thought of this coup to gain time, gradually ceased shaking. But he knocked twice, thrice, four or five times in vain, for the elder Caron was absent about a quarter of a mile in the direction of an old and untenanted stone house in a lonely and almost inaccessible part of the high rocky ground overlooking Bourg-Marie, known as the Manoir, and belonging to himself.

Magloire waited some time, then, turning, half in relief, half in disappointment, back towards the gate, perceived his grandfather coming along the road. The delay had reinstated the younger man in courage. Holding the card out, he drew a long breath as Mikel approached, nearer, nearer, now at the gate, lifting up furry and angry brows at the intruder, reading him all over, trying to place him, to make him out, wondering one minute if it could be Magloire, then resolving the next that Magloire could never look like that, till, as the gate swung to, and the men faced each other, Magloire presented the card with a bow, partly to hide a smile, and partly in recognition of the age and bearing of the [Page 32] old trapper. Any doubts which the latter had had on first view of the stranger vanished on reading the card, for Mikel would be at any time a difficult man to deceive, and there is always something in blood that speaks through many a disguise. He read the card aloud in stumbling English accents, and again looked his grandson over. It was a searching look, but Magloire was now quite at ease. Yet he hesitated to speak, knowing his voice must betray him, and for reasons of his own he preferred to maintain his incognito. Mikel noted with amazement the natty suit, the sparkling ornaments, the perfume, the polished nails, the mixture of colours, the indescribably jaunty, slightly trivial, and impertinent air that country-bred people very frequently acquire after a limited experience of life in cities. At least, Mikel felt all this, although he could not have put it into words, chiefly because he had no words to put it into. But if his vocabulary was limited, his convictions were unalterable. It struck him at once that this person was not of the village. Though he seldom went into it, he knew, and had known, all its types, and this was not one. The word ‘expert’ passed his comprehension entirely; he had, perhaps, never seen it before. ‘Horseflesh’ was almost as bad. The name was English, and the bearer of it, to be supposed, an Englishman, or, more correctly, English-Canadian. And Mikel did not greatly favour the English-Canadians, and would never [Page 33] speak more than was absolutely necessary in the foreign and difficult tongue. In French he now addressed the interloper with the glaring pink cravat and mother-of-pearl studs, size of a half-dollar, whom his heart yearned to welcome as the truant Magloire, but whom his mind half rejected on account of his appearance and his name. Being asked what he was doing there, Magloire had nothing for it but to reply, and the very first word he let drop, his grandfather knew him—knew him, even in the ridiculous garb and the western veneer of cheap culture, even though the pasteboard he held in his hand belied his name and descent; knew him, even while something, a shadow of distrust, of repugnance, of hostility, crept between him and his own kin, the prodigal who had been absent so long! But he gave no sign of recognition. The venerable trapper was a better actor than the youthful ‘expert in horseflesh.’

‘Well,’ said the latter, still swinging his cane in an easy manner, and opening his overcoat for air as well as to display his pink cravat to perfection, ‘I have come to this part of the country almost entirely about horses. I am staying in the village; but I hear you have plenty other animals round here, and I am also buying furs. Ah, yes! I am a horse-trader. I buy whenever I see a good horse; that is my trade, my occupation—and furs. Well, shall we go in?’ [Page 34]

Old Mikel showed no sign of resenting the fact that an impertinent and preposterously-dressed youngster was inviting him to enter his own house. He silently led the way. Presently they were seated, Magloire now occupying the same chair that Laurière had sat in the night before.

‘You want something of me?’ said the old man. ‘Well, that is all right. If it is horses, I have none. I do all my work without horses. I am my own horse. See, you—you have come to the wrong place, then, for horses. There is Messire Jean Thibideau, or le docteur Pligny, in the village, they will have horses to sell, not me. No, I have never owned a horse, and yet I am, or should be, seigneur of Bourg-Marie—of the whole valley. That is strange, you think? Well, yes, it is a little strange.’

There was small discomfiture on Magloire’s part, because he was not one to be easily discomfited, to be at a loss, to be worsted in conversation, in business, in anything. He smiled and took off his overcoat, sitting down again and spreading out his long legs till they appeared, together with those of the elder man, completely to fill the small kitchen. He hesitated, however, a good deal in his speech, for although his English was still imperfect and broken, it was more fluent than his French. He began to wish that his grandfather had recognised him. He had hoped to impress the old man very much with his clothes, and his appearance, and his general [Page 35] important and prosperous self. But Mikel betrayed no admiration. The others—Laurière, Pacifique, his mother, the simple twins, Louis and Jack—admired him. He was even intensely admired out West by the waitresses at the Hallam House, and the chorus-girls at the Opéra Comique; but here, among the primitive and forbidding glooms of the arching pine-forest, and the rush and roar of shimmering torrents, here he was somehow at fault in Mikel’s eyes, though not in his own. And he never dreamt but that Mikel did admire him, but was too ignorant to know why, and too ill-natured to say so.

‘Well,’ he began again, ‘it is clear I get no horses here. Well, that is all right. I can go and see Messire Thibideau in the village, and le docteur as well. But now as to furs.’

‘Well, then, as to furs,’ repeated Mikel.

‘You have, I believe, many kinds of fur? You have bear-skins, for example?’

‘For example, I have bear-skins.’

‘A large number, without doubt?’

‘More than I can count.’

‘Undoubtedly fine, handsome, glossy?’

‘As you have said.’

‘Black or brown?’

‘Both.’

‘The black are considered the most handsome and the most valuable?’ [Page 36]

Mikel appeared to be considering.

‘Not always. There is a brown skin, with an under layer of bronze, as it were, in the colour, that will always fetch a large sum, for it is rare. But the black is most in use.’

‘I myself,’ said Magloire, with superb yet studied carelessness, ‘have a fine cape and gauntlets of black bear. I wear them driving.’

‘Messire Carson is rich, without doubt?’

‘I have made some money. It is in a bank. I have very little with me here. I should be afraid to bring a large amount here.’ And Magloire pointed with his thumb in the direction of the road and forest.

‘And why?’

‘Why? Because no man can be safe here in a wilderness like this—rocks, and stones, and trees, and a very desert of snow, I suppose, after a while. What a country! What a place to live in, to die in! Bah! I shiver already all down my back. I see the dark mornings, the white dazzling noons, the haunted nights, the frost-bound panes, all the horrible winter. I live in better place’ (here he relapsed into English), ‘in Milwaukee.’

‘Ah!’ said Mikel calmly. ‘Then you may have heard of my grandson, Magloire Caron, who, I believe, is in the same town, and doing very well too. Magloire—yes; let me see, it will have been seven years that he has been away—seven.’ [Page 37]

Magloire lost presence of mind. ‘Nine!’ he said, half jumping from his chair. Intolerable to think this old man had actually forgotten the number of years he had voluntarily absented himself!

‘Well—you know him, I see—perhaps nine. I am old—I am likely to forget. What is he like—Magloire?’

‘Ah! like—he resembles such a one as me,’ said Magloire, tapping his chest, sticking his thumbs in his waistcoat, and crossing one leg over the other. ‘He is a fine fellow—in fact, he is now a gentleman, a man of importance, of business. He is a free man, and the citizen of a free country. He is a good Américain.’

‘Well,’ said Mikel, quite gravely, ‘when you see him, Messire Murray Carson, you may tell him you have seen his grandfather, old Mikel Caron, forest-ranger for the County of Yamachiche and seigneur of the valley. Say he is grown old in years, in mind, and in knowledge, but that his arm is still strong to fell a tree, to mark a bear in an ugly way that lasts him till he die, and that his eye and ear and legs and nose haven’t failed him yet. Nor his appetite; nor his temper—he is ugly when he is crossed. Nor his candour; for, to be candid, Messire Carson, if my grandson Magloire be such a one as you, if he dress like you, if he talk like you—a bad French, which is not made better by a frequent bad English, as I understand it is likely to be—I care [Page 38] not if I never see him again, and he is better to remain in his Milwaukee and his States than to return here to Bourg-Marie. It will be, doubtless, that he too would find the winters horrible, the summers stifling, the forests gloomy, the houses poor and uncomfortable, and the people—common. As for gentlemen—ma foi!—there have been no gentlemen here since Champlain died. But as for freedom, we are quite free. Make no mistake, the Canadien is no serf, no slave, no prisoner. We live, it is true, under English rule. Well, it is comfortable. I—I myself do not like these English, but I have nothing to do with them. I leave them alone. I know three words of their language—Government, bear, and damn. They do not molest me, and I ignore them. How are you free, and how is my grandson Magloire free, that I am not free—you cannot show me, for there is nothing to show. Well, you can tell Magloire. Perhaps he will laugh.’

But Magloire did not laugh. He was angry.

‘What!’ he said, in an insulting way that fired even Mikel’s grave and self-contained temper. ‘You, an old man, grown old in the depth of this frightful forest, in this hole of a hut, fed on bear’s meat and onions, and saying your prayers to a sly dog of a priest, why, you are no better than a savage, let alone a serf! You are mad to talk to me like that! Come, about these skins—I want to purchase some. Let me see them.’ [Page 39]

‘They are not here,’ said the imperturbable Mikel.

‘Where are they, then?’

‘I do not tell where they are. It is not my custom.’

‘Will you tell me the price of one?’

‘They are not for sale.’

‘Not to anyone?’

‘They might be to someone.’

‘And that one?’

Mikel remained silent.

‘It will be to the Government you sell, I see,’ said Magloire composedly.

He still had the grand coup left. Were a sight on a share of the furs denied him as an American trader, as a Government emissary, as an interested individual, all he had to do was to stand up, proclaim his origin, extend his arms, and clasp his loving grandfather in them, and the furs were his.

‘I do not intend to buy alone for myself,’ he went on. ‘I have a partner, who will be equally anxious that I should procure some of these rich skins in which your country abounds. Without doubt I must write to my friends at Quebec, who are in the Government offices, for an order to see your furs. I do not wish to leave the country without a chance of seeing and perhaps buying some. I have several friends who are of the Government. That will be easy.’

‘At least, it will not be difficult,’ said Mikel.

‘When I hear from these friends then I shall [Page 40] come again, pay you another visit, and you will show me the furs, eh?’

‘I have not said so.’

‘But you are of that intention?’

‘Of a certainty, no. I have already told you, Messire Murray Carson, that it is not my custom to sell or show my furs to anyone.’

‘Unless of the Government?’

‘Have I said so?’

A moment’s silence, then Magloire chose to make his grand coup. He rose, and turned his really handsome and engaging countenance towards the old man, and said in his sweetest tones, and with all the oratory natural to the French, which it takes a very long domestication abroad to eradicate:

‘Mon père’ (my father), ‘look at me. Regard well thou thy son, le p’tit Magloire. It will have been better, perhaps, that I spoke at first. But I thought—the trouble, the misery of the heart, the sorrow—and caused by me! Mon père, forgive me! In truth, ’tis I, le p’tit Magloire, your grandson.’

There was every symptom of joy, every sign of genuineness, every indication of filial love and reverence in the glowing countenance, the smiling mouth, the glistening eyes, the outstretched arms. These French are the finest natural comedians in the world, and can play more than two parts at once. But where was the trembling, grateful, appalled, and overjoyed recipient of these oratorical favours? [Page 41]

Mikel simply cast up the whites of his eyes to the smoke-blackened ceiling, and brought his pipe out of his pocket.

‘You were a foolish child always,’ he said, ‘and you are no wiser now. Did you carry away with you nothing more of my character than to suppose for a moment that I could be deluded into thinking Messire Murray Carson a different person from Magloire Caron, coachman? If so, you should have known better. You were fourteen when you ran away. That is a good age for a boy. He ought to be able to judge a little—well, of those with whom he has lived, those who have fed and housed and educated him—well, it was not a school, but it was better than a school, perhaps—who would have educated him.’

Magloire, surprised, defeated, though not in the least humiliated, succumbed to defeat as gracefully as he had thought to conquer, and simply shrugging his shoulders, sat down again, having not folded his aged relative in his long and sinewy arms as he had expected to do.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘I was away so long—it will be nine years that I have been in those States—and I thought—Mikel, he will not know me again, and that will be funny. I can talk to him as if I were another man, perhaps about myself—funny too—and there will be no trouble. And I thought, it will be the more easy and pleasant way for both after so long an [Page 42] absence. Well, all that, there was nothing wrong in that.’

‘No,’ said his grandfather, who was by this time placidly smoking, though still furtively engaged in noting the extraordinary attire and appearance of the prodigal. ‘I have not said that there was anything wrong. One is quite free at your age—you should be no longer a child—to do as he wishes. For example, your business, your affairs. You have prospered, Laurière has said. I am glad of that; that cannot fail to give me joy, as it renders me no longer responsible for you. For instance, when I thought of your coming home at all, I thought sometimes of you as coming home poor.’

‘In that case?’ said Magloire.

‘In that case, I could do nothing for you. I am not a rich man.’

‘These furs, skins, these forests, rivers—they are all yours.’

‘They do not make me rich. They do not constitute wealth.’

‘They should.’

‘They might in the hands of another man; not in mine. And if I were a rich man, I should do nothing for you if you were poor.’

‘Because I ran away?’

‘Of a truth, because you ran away. It is true that I care little for companions. My companions are the stars, the streams, the trees in the forest, the [Page 43] boulders in the valley. Under these I sometimes sleep; against them I lean. I look up at them as at old and trusted friends. I wade through them, loving their clear and cold sparkling depths. When I have these, then I want no man. And should I want a man, I have him. There is your uncle, Joncas; there are one or two others. Yes, I have companions. Therefore I do not want you; nor did I ever want you. But you did wrong, all the same, to run away, for you were my heir.’

‘Your what?’ said Magloire, in astonishment, and he added, in English, ‘This is too much! Well, I bet you I make him tell me what I get when he die. There will be, it is likely, more than furs and skins.’

The old man caught the sense of this remark.

‘Yes,’ he said; ‘without a single skin you would still inherit something: the forest itself, the valley, the banks of the Yamachiche—well, the village, the old Manoir, the cleared acre and a half, and all that lives and roams in and throughout this district. Think well; that is what you have lost, and with it the title of seigneur.’

‘A fine title!’ said Magloire, though satirically, yet without bitterness. It was inconceivable that a young man who had aspired to be a bar-tender in Minneapolis, a waiter in Chicago, a barber’s assistant in Kalamazoo, and a coachman in Milwaukee, should entertain any dream of becoming seigneur of a [Page 44] desolate, gloomy, bear-haunted tract of uncleared forest and lonely river in Lower Canada. ‘A pretty title!’ repeated Magloire. ‘Why, I would rather black boots and run messages in the States! I should be freer than call myself seigneur of this miserable hole.’

‘That is to your own taste,’ said Mikel. ‘It would not be to mine.’

‘Because, of a truth, you have never known anything else,’ said the grandson. ‘Because you know nothing of the world. I, now, I have seen a good deal. You live in Canada, in this place, all your life. You see nothing, you hear nothing, you meet nobody. The curé is your oracle; you do not even read a paper. You and your race—even the English know this—are priest-ridden, chained, made slaves, prisoners. Nothing you have is your own; it is all for the Government or the priest. Well, I, now, I myself when I left here, I was like that, too. When I went first from here I stop at Quebec. There was the money you gave me to pay Joncas in the village—that little debt, you remember—and I did not pay, but took the money and went to Quebec. There I, too, sought out a priest, and told him I was alone and without work or place in the world, and was tired of Bourg-Marie. And he was very kind, as such men can be, and found me where I could board. But he took the rest of my money—ma foi, yes, he did that, and said it would be in trust for me when [Page 45] I came back, safe in the Church’s care; for I had met with a party of Americans, young men from the shanties who were going out to Michigan. Yes, sir. Well, I make friends quick—they call me fool for staying in Canada—and I went with them. But I never got that money back from the priest.’

‘And this card, this name of Messire Murray Carson. This will be your partner, without doubt?’

‘Ah no,’ replied Magloire. ‘Of a truth, that is my own name, the name I have just lately taken out in Milwaukee. My affairs—see—well, the English name serves me better.’

‘Possibly, your own not being good enough.’

‘It is French, it is French. And I have found lately that it was against me, my being French.’

‘That is a pity.’

‘But I shall soon correct that. You will perceive that already I do not speak so good French as you, although, indeed, it is but poor French anyone speaks here. It is not French at all.’

‘How do you call it, then? It is the language bequeathed us by our ancestors. I speak as spoke Champlain, as spoke my great-great-grandfather. It satisfies me, and I have heard a traveller say that it is very pure, though, without doubt, very old French, and free from intrusions of English idiom.’

But these remarks of the old man were totally beyond the comprehension of Magloire, as might be expected. While his grandfather spoke, upholding [Page 46] the tradition of his mother-tongue, Magloire was surveying the room and wondering where the skins, if they really existed, and were not the figment of a dream evolved from Laurière’s luxurious fancy, could be hidden. Although he did not quit his chair, old Mikel followed his gaze, comprehending perfectly its intent.

‘They are not here,’ he said.

‘Well, is it kind to treat me so like a stranger whom you cannot trust? I only want to see them.’

‘You have said that your partner has required of you to purchase some. You are not truthful. Nor do I yet understand what your affairs are. Laurière, he has told me, Nicolas Laurière, that you were a coachman. You show me this card, you speak of trading in horses, then you wish to purchase furs.’

‘It is all true;’ and Magloire nodded. ‘I am not of one thing, but of many. That is the way one prospers in these States. One has to try many things, prove one’s self, find what one can do best, refuse nothing, accept anything, fail often, begin over again. Enfin—one hits the right nail. Yes, sir, I have much business, I am in demand, everyone knows me; I belong to two societies, I walk in their processions, I speak in a crowded hall. I have brains, ideas; I am not afraid to speak out; they all listen to me. I shall speak here. I wish to take the large room at Delorme’s next Friday, and address there the village.’ [Page 47]

‘Will it be in English, or in French, this address?’

Magloire stared. His grandfather’s sarcasm was too quiet for him to resent, too subtle for him to fully grasp.

‘It will be in French, without doubt.’

‘And the subject?’

‘L’émancipation!’ Magloire flourished his right hand in the air, while with the other he produced from his coat a thick packet of newspapers tied with a string. ‘At least you will attend there? You will assist with your presence?’

‘It is possible.’

Magloire laughed in secret. The old fox, old weasel, old man-of-the-woods, was jealous. He, Magloire, had come back well, gaily dressed, a gentleman—or as good as one—able to read, and write, and speak in public, address and move his fellow-countrymen, and the old man was jealous of his ability, his education, his appearance. Magloire laughed aloud and rose to depart.

‘Since you do not show me the furs to-day, I will go,’ said he. ‘Some other time, eh?’

Mikel gave no answer whatever at first.

‘When do you leave?’ he said finally.

‘Well, I do not know. I shall wait for that order from Quebec, for other things. My partner, he may join me here. I cannot tell when I go. I walk, now when I leave you, to see my Uncle Joncas and [Page 48] the rest in the village. I shall find it just the same?’

‘There will be no change.’

‘Of that there is no fear. It waits for me, Magloire Caron, does it not, to change it?’

Old Mikel rose and drew himself up. He was fully as tall as his grandson, when not laden with weapons or tools, and the two men faced each other.

‘It waits for no such person, for no such person exists. There is no Magloire Caron. It waits, say you yourself, for Messire Murray Carson.’

An angry look crept in Magloire’s keen eyes.

‘You cannot rob me of my name.’

‘You have robbed yourself.’

‘Even if I choose to take an English name, I may yet require to use my French one.’

‘You may indeed.’

‘Then, if so, I shall use it.’

‘Good. I have no objection. There may easily be more than one Magloire Caron in the world.’

‘You will then disown me?’

‘You shall see.’

Upon this, Magloire, with a final shrug—a habit his residence in a foreign country had not yet counteracted—lit a cigar and took his leave. There did not seem to offer any excuse for his remaining. His grandfather was old, foolish, out of his head a little, obstinate, angry, jealous—jealous! Very well; there was plenty of time. He would try again. All [Page 49] would come in time. Old people were all like that.

Mikel waited till Magloire had entirely disappeared in the direction of the village, straight along the road that led back from where he had started—the widow Péron’s cabin—waited silently, with listening ear and bated breath, as so often his mode of life led him to wait for stealthy, gliding animal, or swift fish, or wheeling bird, until he told himself Magloire had certainly gone to the village. So keen already was his sense of hostility, and so small his belief in the straightforwardness of his grandson, so true was his perception, not blunted by use nor at fault through myriad daily abuses, and so rapid his conclusions, formed maybe hastily, but founded on impulses which were natural, simple, and untainted. Such a life and occupation as Mikel’s made and left him simple, but sound. No multitude of daily trivial complexities had ever crossed and recrossed the clear sky of his life as the modern net-works of electric lines obscure the daylight in crowded city thoroughfares. All about him was open in reality, although much of it had to do with a system of ambush, decoy, and destruction that might have perverted a nature less rigidly virtuous, truthful, and consistent. But, nevertheless, he had one secret. [Page 50]

CHAPTER IV.

THE OLD MANOIR.

‘Mine age is departed, and is removed from me as a shepherd’s tent. I have cut off, like a weaver, my life.’

MAGLOIRE, then, had returned, and his grandfather pondered long over the singular alteration in him, not sharing with the others in their admiration of his arrogant manner and gaudy attire. He condemned his jewellery, his choice of colours, his pungent cigar, as much as he condemned his opinions.

Waiting till Magloire was out of sight, he carefully locked his door, and, going out of the back enclosure, proceeded stealthily through a fir plantation to the old and deserted stone building known as the Manoir. There were two ways of approaching it, and he had now chosen the one most inaccessible to others, the path being rarely trodden by anyone but himself, and completely hidden from the frequenters of the ordinary highroad that led before his front-door to the village on one hand, [Page 51] and through the forest on the other. Along this footpath—it was no wider—Mikel walked with a heavier weight upon his heart and brain than he had ever borne upon back and shoulders up that ever-increasing declivity. For the path, growing steeper and steeper, though still cut through thick-growing firs and hemlocks, emerged at length upon a triangular garden—a kind of ‘close,’ in fact, shut in on two sides by trees sloping almost imperceptibly in the direction of the third side, which was bounded by the long, irregular low stone mansion built about the year of our Lord 1670, and called the Manoir.

In this stone house had the Chevalier Jules-Gaspard-Noël-Ovide Delaunay-Colombière Caron lived for fifty-five scorching summers and Arctic winters, sudden and magical springs, and luminous, hazy, and golden autumns. Here had he witnessed the slow but steady decline of all the prerogatives and prejudices dear to the aristocratic French mind of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Here had he struggled in spite of inclement climatic forces, of few and suspicious neighbours, and of a constantly changing and unsettled country, to maintain the dignity and state due to the person of a French gentleman, well born, town bred—for the ancient family seat in France was inside the famous city of Rouen, and is still to be seen, a feudal manor, one half in ruins, the other half turned into a charity school—and possessed of much of the varied and [Page 52] quaint learning, and all the airs and graces of the time. A friend of that M. D’Avaugour who wrote from Canada, ‘La Nouvelle France,’ in 1661, ‘I have seen nothing to equal the beauty of the River St. Lawrence,’ he, in company with many other enthusiasts, emigrated partly to soothe the wounded feelings which Colbert, ‘cet homme de marbre,’ as he was called by Gui Patin, ‘avec des yeux creux, ses sourcils épais et noirs, esprit solide mais pesant,’ had, to do him justice, unwittingly outraged by a presentation of a financial post at Rheims to Le Caron’s elder brother, and partly from a desire to distinguish himself in a new and not overcrowded land. Even in 1668 the world—at least, that part of it that surged and strove and whined and cajoled and fought and elbowed and cursed and smiled and intrigued and blasphemed and prayed—all in the same breath—around that Court of Louis XIV.—began to find itself in its own way and its own sphere all too small. Of the delights, the temptations, the pains, the shames of such a life, had Colombière Caron already tasted. The young King very soon recognised his character and abilities, and, judging correctly that he was at heart disinclined to the dangerous pleasures of a Court, and by a simple seriousness of mind and disposition quite as unfitted for the perilous posts within the gift of that Court, held out promises of fortune, land, and distinction in the new France across the water. [Page 53] In reality, however cruel the deception may have proved to be in one or two ways, the action of Louis was a kind one. Le Caron embarked not without misgivings, but with more than a tincture of hope. He knew well that he was not the first French gentleman of a noble house and distinguished line to settle in the primeval glooms and snowy fastnesses of ‘La Nouvelle France.’

Sieur D’Avaugour’s opinion weighed much with him. No country so exquisitely beautiful as he had depicted in his letters home (Baron Pierre Dubois D’Avaugour, Governor of New France from 1661-1663) could hold discomforts so great as those sketched, say, in the relations of the Jesuits and other missionary records. The illustrious Champlain’s memory survived even in the mêlée of those latter days under the Great Louis. What he had borne another French gentleman could.

Le Caron, yielding to pressure of many kinds, sailed at last for the land of snow and pines, to be followed by many another scion of the haute noblesse—witness the names that constantly recur in the documents relating to the old French régime on from that time up to the taking of Quebec in 1759—Le Gardeur de St. Pierre, Le Baron de Longueuil, Le Chevalier St. Ours, Le Chevalier de Niverville, De Ramezay, D’Argenteuille Daillesbout, Le Verrier, Livaudière Péan, and scores of others of varying rank, age, celebrity, ability, and fortune. But at [Page 54] the time when Mikel’s ancestor arrived one stormy March in a vessel called Le Chameau—though not the vessel of that name which was wrecked in 1725 with the Intendant de Chazel on board—he was one of a very small number indeed of cultivated and courtly gentlemen grafted with all the French virtues and not a few of the French vices upon the new and struggling colony. Le Caron, however, was singularly destitute of vices, and, quickly resigning himself to his future abode and surroundings, and calling upon his family to preserve the like equanimity, he took possession according to letters patent recently delivered to him by permission of His Most Gracious Majesty of the fief and grant of land consisting of the Plutonian realms of forest, and the half-frozen river of the Yamachiche, just stirring beneath its icy hood to life and conscious beauty. Like all pioneers, the sudden change to a green and lustrous spring enchanted him. The fresh untired, untried earth took on for him a truly celestial hue. Nothing came amiss, not even the heat of July and August. The only thing he and his family and servants dreaded was the cold, and so, wintering in military quarters at Quebec, they escaped the tortures of the first year’s frost, while by the time the second winter was upon them, behold, the Manoir was sufficiently advanced to permit of occupation.

No wonder that old Mikel, the forest-ranger of the nineteenth century, should so reverence and [Page 55] adore the habitation of his ancestors, built in the seventeenth. The triangular garden was sodded, carefully swept clean of fallen leaves, in itself no light task, inasmuch as the October winds were playing sad havoc with maple and oak and brown pine tassel, and bore in its centre a kind of piled-up grotto of most beautiful rough blocks of serpentine and native marble that only required polishing to render them highly lustrous, smooth, and of the richest colours. Upon the top of this cairn, or grotto—it was neither the one nor the other, yet something like both—stood an image of a Cupid, rudely carved from the same gray stone that composed the dwelling-house and offices. The Cupid was sadly out of place in this remote and lonely region. But he doubtless served to carry the memory back to the gay gardens of the luxurious France from which his creator had come. This was no less a person that Père Chaletot, the chaplain and confidential friend of Messire Jules-Gaspard-Noël-Ovide Delaunay-Colombière Caron, a character whose fame had reached old Mikel by word of mouth and document, who had been steward, priest, carver, dispenser, tutor, purveyor, overseer, draughtsman, gamekeeper, and physician, all in one. Carved seats that had originally been stumps of gigantic trees surrounded the grotto, also the work of the accomplished Père Chaletot, and the greatest care and wealth of imagination had [Page 56] evidently been spent on their production. One was an armchair, deep, capacious, luxurious, and, in place of cushions, large growths of moss, emerald green, brown, and gray, filled in all its corners. Another was a sentry-box open at the roof; this one having clearly been adapted from the hollow trunk of a decaying tree, and furnished now with a seat inside, and more cushions of moss for the back and shoulders. A third was as much as possible like a box at the opera, having a horseshoe-shaped ledge in front, upon which it used doubtless to please the Reverend Father and his pupils and protégés to lean, under the impression that they were about to witness a performance of a new comedy or an airy ballet du cour. Whitened, some of them, by rain and storm and old age, ant-eaten and mouldering the others, these strange carven seats seemed always waiting for the arrival of guests who never came, guests who, when they did appear, might prove but ghosts.

The Cupid, wan and cold and wizened, gazed ruefully—or so it seemed—upon the circle of fast-decaying seats that had not been occupied for so long, not since the grandson of Sieur Jules-Gaspard le Caron celebrated his coming of age by trying to work a fountain under the grotto, and inducing all the household to come down and give the invention welcome. Alas! the birthday was in November, and the water froze while the guests sat around shivering, waiting for the first glittering drops to fall, catching [Page 57] the light as they fell, and reminding them of the sparkling jets some of the older ones had seen in the country of the fleur-de-lis, now receding further and further into oblivion. The birthday was in November, and Cupid looked as he felt, intensely cold, and would have been glad of some straw tied about him as they tied up the urns and flowers in France, but nobody thought of it.

At the apex of the triangle of sward, just where Mikel’s footpath came to an end, stood a little shrine or raised crucifix, with a rudely-carved figure of the Saviour upon it, also the work of the gifted Chaletot. At one time the crucifix had been gilded, and some touches of colour had been added to the face of the suffering Christ; but in Mikel’s time, though he had looked often and carefully, he had never been able to detect either gold-leaf or carmine upon its wasted and unsymmetrical proportions. A gravel-walk bordered the sward, separating it from the thick plantation and the long terrace that swept from one end to the other of the Manoir itself. Three flower-beds cut in the shape of the royal lilies of France—beloved France! according to Sir William Temple, ‘Ce noble et fertile royaume, le plus favorisé par la nature de tous ceux qui soit au monde’—and a fourth representing a crown, testified to the unimpeached loyalty of the high-bred gentleman under whose supervision they had probably been cut out in Canadian turf. [Page 58]

But neither curious carven seat, nor design of crown and lily, nor shape of stone crucifix, recalled to the mind the fair country seats of France so much as the long Manoir itself; nearly two hundred feet from end to end, and its two tall towers at either side seventy feet in height. The exact miniature of many a French château in style, it was only a miniature after all, its dimensions being far inferior to those of the Château of Pierrefonds, for example, built in feudal times and restored by the late Napoleon III., or the magnificent Château of Vincennes, surrounded by the orthodox towered wall and moat, or the smaller Château of Luynes, in which died its owner, Albert de Luynes, in the year 1621, of fever. It was over the body of this Albert de Luynes that two of his valets de chambre fought at cards while they were feeding the horses which were carrying him to his burial. The terrace, the two end towers, rounded in true feudal fashion, the central cluster of similar turrets or towers, and the innumerable small windows, doors, steps and pointed rods on the roof that once had borne flags, were all more or less faithful reproductions of the country châteaux that dotted the beautiful plains, and crowned the wooded hills, and nestled in the corn-clad valleys of France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But while the plan was correct, the building itself had been evidently far from satisfactory in the matter of duly quarrying, laying, cementing and piling the stone, [Page 59] and in details of measurement, allowance for shrinkage, and proportion. Gaps in the cold gray stone were frequent, and the whole building had sunk a foot or more beneath the original level of the turf. The walls, though enormously thick in some places, had all fallen away from the perpendicular, and but little glass, and that, of course, of a rude description, could be found in the windows. The upper portion was the best preserved, and if a line had been drawn cutting off the ten feet at the top, the lower part would have passed for some vacated farm or battered grange, so ordinary was that section of the building where the long windows opened on the wooden terrace.