A

GOOD BOOK

IS THE

PRECIOUS

LIFE-BLOOD

OF A

MASTER

SPIRIT

Milton

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

GENERAL EDITOR

SIR A. T. QUILLER COUCH

[unnumbered page]

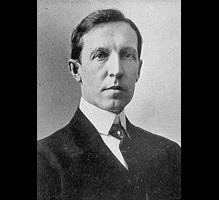

[illustration:

C. G. D. ROBERTS]

NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY

[unnumbered page]

MORE

ANIMAL

STORIES

BY

CHAS. G. D. ROBERTS

M. DENT & SONS . LTD . LONDON & TORONTO

[unnumbered page]

All rights reserved

SOLE AGENT FOR SCOTLAND

THE GRANT EDUCATIONAL CO. LTD.

GLASGOW

FIRST EDITION, June 1922 REPRINTED, September 1922

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

[unnumbered page]

CONTENTS

|

PAGE |

|

| THE FISHERS OF THE AIR |

7 |

| MUSTELA OF THE LONE HAND |

22 |

| MISHI |

37 |

| THE WINGED SCOURGE OF THE DARK |

67 |

| THE LITTLE HOMELESS ONE |

83 |

| THE SUN-GAZER |

103 |

[page 5]

For permission to print “The Sun-Gazer” from Kings in Exile, acknowledgement is due, and is hereby made, to the Macmillan Co., of New York, the publishers of that volume in the United States (Copyright 1910) and in Canada.

With respect to the same story, acknowledgement is also made to Messrs. Ward, Lock, and Co., the publishers in Great Britain of Kings in Exile. [page 6]

MORE

ANIMAL STORIES

THE FISHERS OF THE AIR

THE lake lay in a deep and sun-soaked valley facing south, sheltered from the sea-winds by a high hog-back of dark green spruce and hemlock forest, broken sharply here and there by outcroppings of white granite.

Beyond the hog-back, some three or four miles away, the green seas creamed and thundered in sleepless turmoil against the towering black cliffs, clamorous with seagulls. But over the lake brooded a blue and glittering silence, broken only, at long intervals, by the long-drawn, wistful flute-cry of the Canada whitethroat from some solitary tree-top:

Lean—lean—lean-to-me—lean-to-me—lean-to-me—of all bird voices the one most poignant with loneliness and longing.

On the side of the lake nearest to the hog-back the dark green of the forest came down to within forty or fifty paces of the water’s edge, and was fringed by a narrow ribbon of very light, tender green—a dense, low growth of Indian willow, elder shrub, and a withewood, tangled with white clematis and starred with wild convolvulus. From the sharply-defined edge of this gracious tangle a beach of clean sand, dazzlingly white, sloped down to and slid beneath the transparent [page 7] golden lip of the amber-tinted water. The sand, both below and above the water’s edge, was of an amazing radiance. Being formed by the infinitely slow breaking down of the ancient granite, through ages of alternating suns and rains and heats and frosts, it consisted purely of the indestructible, coarse white crystals of the quartz, whose facets caught the sun like a drift of diamonds.

The opposite shores of the lake were low and swampy, studded here and there with tall, naked, weather-bleached “rampikes”—the trunks of ancient fir trees blasted and stripped by some long-past forest fire. These melancholy ghosts of trees rose from a riotously gold-green carpet of rank marsh-grasses, sweeping around in an interminable, unbroken curve to the foot of the lake, where, through the cool shadows of water-ash and balsam-poplar, the trout-haunted outlet stream rippled away musically to join the sea some seven or eight miles farther on. All along the gold-green sweep of the marsh-grass spread acre upon acre of the flat leaves of the water-lily, starred with broad, white, golden-hearted, exquisitely-perfumed blooms, the paradise of the wild bees and honey-loving summer flies.

Over this vast crystal bowl of green-and-amber solitude domed a sky of cloudless blue, and high in the blue hung a great bird, slowly wheeling. From his height he held in view the intense sparkling of the sea beyond the hog-back, the creaming of the surf about the outer rocks, and the sudden upspringing of the gulls, like a puff of blown petals, as some wave, higher and more impetuous than its predecessor, drove them from their perches. But the aerial watcher had heed only [page 8] for the lake below him, lying windless and unshadowed in the sun. His piercing eyes, jewel-bright, and with an amazing range of vision, could penetrate to all the varying depths of the lake and detect the movements of its finny hordes. The great sluggish lake-trout, or “togue,” usually lurking in the obscurest deeps, the shining, active, vermilion-spotted brook-trout, foraging voraciously nearer the shore and the surface, the fat, mud-loving “suckers,” rooting the oozy bottom like pigs among the roots of the water-lilies, the silvery chub and the green-and-gold, fiercely-spined perch haunting the weedy feeding-grounds down toward the outlet—all these he observed, and differentiated with an expert’s eye, attempting to foresee which ones, in their feeding or their play, were likely soonest to approach the surface of their glimmering golden world.

Suddenly he paused in his slow wheeling, dipped forward, and dropped, with narrowed wings, down, down from his dizzy height to within something like fifty yards of the water. Here he stopped, with wings wide-spread, and hovered almost motionless, slowly sinking like a waft of thistledown when the breeze has died away. He had seen a fair-sized trout rise lightly and suck in a fly which had fallen on the bright surface. The ringed ripples of the rise had hardly smoothed away when the trout rose again. As it gulped its tiny, half-drowned prey, the poised bird shot downward again—urged by a powerful surge of his wings before he closed them—this time with terrific speed. He struck the water with a resounding splash, disappeared beneath it, and rose again two or three yards beyond with the [page 9] trout securely gripped in his talons. Shaking the bright drops in a shower from his wings, he flapped hurriedly away with his captive to his nest on the steep slope of the hog-back. He flew with eager haste, as fast as his broad wings would carry him; for he feared lest his one dreaded foe, the great white-headed eagle, should swoop down out of space on hissing pinions and rob him of his prize.

The nest of the osprey was built in the crotch of an old, lightning-blasted pine which rose from a fissure in the granite about fifty feet above the lake. As the osprey had practically no foes to be dreaded except that tyrannical robber, the great white-headed eagle—which, indeed, only cared to rob him of his fish, and never dared drive him to extremities by appearing to threaten his precious nestlings—the nest was built without any pretence of concealment, or, indeed, any attempt at inaccessibility, save such as was afforded by the high, smooth, naked trunk which supported it. An immense grey, weather-beaten structure, conspicuous for miles, it looked like a loose cartload of rubbish, but in reality the sticks and dried rushes and mud and strips of shredded bark of which it was built were so solidly and cunningly interwoven as to withstand the wildest of winter gales. It was his permanent summer home, to which he and his handsome, daring mate were wont to return each spring from their winter sojourn in the sun lands of the south. A little tidying-up, a little patching with sticks and mud, a relining with feathers [page 10] and soft, winter-withered grasses, and the old nest was quickly ready to receive the eggs of his mate—beautiful and precious eggs, two, three, or four in number, and usually of the rich colour of old ivory very thickly splashed with a warm purplish brown.

This summer there were four nestlings in the great untidy nest; and they kept both their devoted parents busy, catching and tearing up into convenient morsels fish enough to satisfy their vigorous appetites. At the moment when the father osprey returned from the lake with the trout which he had just caught they were full-fed and fast asleep, their downy heads and half-feathered, scrawny necks comfortably resting across one another’s pulsing bodies. The mother-bird, who had recently fed them, was away, fishing in the long green-grey seas beyond the hog-back. The father, seeing them thus satisfied, tore up the trout and swallowed it, with dignified deliberation, himself. Food was plentiful, and he was not over-hungry. Then, having scrupulously wiped his beak and preened his feathers, he settled himself upright on the edge of the nest and became apparently lost in contemplation of the spacious and tranquil scene outspread beneath him. A pair of bustling little crow-blackbirds, who had made their own small home among the outer sticks of the gigantic nest, flew backwards and forwards diligently, bringing insects in their bills for their naked, newly-hatched brood. Their metallic black plumage shone iridescently, purple and green and radiant blue, in the unclouded sunlight, and from time to time the great osprey rolled his eyes upon them with a mild and casual interest. Neither [page 11] he nor his mate had the slightest objection to their presence—being amicably disposed towards all living creatures except fish and possible assailants of the nest. And the blackbirds dwelt in security under that powerful, though involuntary, protection.

The osprey, the great fish-hawk or fish-eagle of Eastern North America, was the most attractive, in character, of all the predatory tribes of the hawks and eagles. Of dauntless courage without being quarrelsome or tyrannical, he strictly minded his own business, which was that of catching fish; and none of the wild folk of the forest, whether furred or feathered, had cause to fear him so long as they threatened no peril to his home or young. On account of this well-known good reputation he was highly respected by the hunters and lumbermen and scattered settlers of the backwoods, and it was held a gross breach of the etiquette of the wilderness to molest him or disturb his nest. Even the fish he took—and he was a most tireless and successful fisherman—were not greatly grudged to him; for his chief depredations were upon the coarse-fleshed and always superabundant chub and suckers, which no human fisherman would be at the trouble to catch.

With all this good character to his credit, he was at the same time one of the handsomest of the great hawks. About two feet in length, he was of sturdy build, with immensely powerful wings whose tips reached to the end of his tail. All his upper parts were of a soft dark brown, laced delicately and sparsely with white, and the crown of his broad-skulled, intelligent head was heavily splashed with white. All his underparts [page 12] were pure white except the tail, which was crossed with five or six even bars of pale umber. His long and masterful beak, curved like a sickle and nearly as sharp, was black; while his formidable talons, able to pierce to the vitals of their prey at the first clutch, were of a clean grey-blue. His eyes, large and full-orbed, with a beautiful ruby-tinted iris encircling the intense black pupil, were gem-like in their brilliance, but lacked the implacable ferocity of the eyes of the eagle and the goshawk.

Presently, flying low over the crest of the hog-back with a gleaming mackerel in her talons, appeared his mate. Arriving swiftly at the nest, and finding the nestlings still asleep, she deposited the mackerel in a niche among the sticks, where it lay flashing back the sun from its blue-barred sides, and set herself to preening her feathers, still wet from her briny plunge. The male osprey, after a glance at the prize, seemed to think it was up to him to go her one better. With a high-pitched, musical, staccato cry of Pip-pip—pip-pip—pip-pip—very small and childish to come from so formidable a beak—he launched himself majestically from the edge of the nest and sailed off over the hot green tops of the spruce and fir to the lake.

Instead of soaring to his “watch-tower in the blue,” he flew now quite low, not more than fifty feet or so above the water; for a swarm of small flies was over the lake, and the fish were rising to them freely. In every direction he saw the little widening rings of ripple, each of which meant a fish, large or small, feeding at the surface. His wide, all-discerning eyes could pick [page 13] and choose. Whimsically ignoring a number of tempting quarry, he winnowed slowly to the farther side of the lake, and then, pausing to hover just above the line where the water-lilies ended, he dropped suddenly, struck the water with a heavy splash, half submerging himself, and rose at once, his wings beating the spray, with a big silver chub in his claws. He had his prey gripped near the tail, so that it hung, twisting and writhing with inconvenient violence, head downwards. At about twenty-five or thirty feet above the water he let it go, and swooping after it caught it again dexterously in mid-air, close to the head, as he wanted it. In this position the inexorable clutch of his needle-tipped talons pierced the life out of the chub and its troublesome squirming ceased.

Flying slowly with his solid burden, he had just about reached the centre of the lake when an ominous hissing in the air above warned him that his mighty foe, from far up in the blue dome, had marked his capture and was swooping down to rob him of the prize. He swerved sharply, and in the next second the eagle, a wide-winged, silvery-headed bird of twice his size, shot downward past him with a strident scream and a rustle of stiff-set plumes, swept under him in a splendid curve, and came back at him with wide-open beak and huge talons outspread. He was too heavily laden either to fight or dodge, so he discreetly dropped the fish. With a lightning swoop his tormentor caught it before it could reach the water, and flew off with it to his eyrie in a high, inaccessible ravine at the farthest end of the hog-back, several miles down the outlet stream. The osprey, taking quite [page 14] philosophically a discomfiture which he had suffered so many times before, stared after the magnificent pirate angrily for a few seconds, then circled away to seek another quarry. He knew that now he would be left in peace to enjoy what he might take.

But this time, in his exasperated anxiety more than to make good his loss, his ambition somewhat overreached itself. To borrow the pithy phrase of the backwoodsman, he “bit off more than he could chew.”

One of those big grey lake-trout, or “togue,” which, as a rule, lurk obstinately in the utmost depths, rose slowly to investigate the floating body of a dead swallow. Pausing a few inches below the surface, he considered as to whether he should gulp down the morsel or not. Deciding, through some fishy caprice, to leave it alone—possibly he had once been hooked, and broken himself free with a painful gullet!—he was turning away to sink lazily back into the depths when something like a thunderbolt crashed down upon the water just above him, and fiery pincers of horn fixed themselves deep into his massive back.

With a convulsive surge of his broad-fluked, muscular tail he tried to dive, and for a second drew his assailant clean under. But in the next moment the osprey, with a mighty beating of wings which thrashed the water into foam, forced him to the surface and lifted him clear. But he was too heavy for his captor, and almost immediately he found himself partly back in his own element, sufficiently submerged to make mighty play with his lashing tail. For all his frantic struggles, however, he could not again get clear under, so as to make [page 15] full use of his strength; and neither could his adversary, for all his tremendous flapping, succeed in holding him in the air for more than a second or two at a time.

And so the furious struggle, half upon and half above the surface, went on between these two so evenly-matched opponents, while the tormented water boiled and foamed and showers of bright spray leapt into the air. But the osprey was fighting with brains as well as with wings and talons. He was slowly but surely urging his adversary over toward that white beach below the hog-back, where, in the shallows, he would have him at his mercy and be able to end the duel with a stroke or two of his rending beak. If his strength could hold out till he gained the beach, he would be sure of victory. But the strain, as unusual as it was tremendous, was already beginning to tell upon him, and he was yet some way from shore.

His mate, in the meantime, had been watching everything from her high perch on the edge of the nest. At sight of the robber eagle’s attack and his theft of the chub her crest feathers had lifted angrily, but she had made no vain move to interfere. She knew that such an episode was all in the day’s fishing, and might be counted a cheap way of purchasing immunity for the time. When her gallant partner first lifted the big lake-trout into the air, her bright eyes flamed with fierce approval. But when she saw that he was in difficulties her whole expression changed. Her eyes narrowed, and she leaned forward intently with half-raised wings. A moment more, and she was darting with swift, short wing-beats to his help. [page 16]

By the time she arrived the desperate combatants were nearing the shore, though the big fish was still resisting with undiminished vigour, while his captor, though undaunted, was beginning to show signs of distress. With excited cries of Pip-pip, pip-pip, she hovered close above her mate, seeking to strike her eager talons into his opponent’s head. But his threshing wings impeded her, and it was some moments before she could accomplish it without hampering his struggles. At last she saw her opportunity, and with a lightning pounce fixed her talons upon the fish’s head. They bit deep, and through and through. On the instant his struggles grew feeble, then died away. The exhausted male let go his hold and rose a few yards into the air on heavy wings; while his victorious mate flapped inwards to the beach, half carrying her prey, half dragging it through the water. With a mighty effort she drew it clear up on the silver sand. Then she dropped it and alighted beside it, with one foot firmly clutching it in sign of victory. Her mate promptly landed beside her, whereupon she withdrew her grip, in acknowledgment that the kill was truly his.

After a few minutes’ rest, during which the male bird shook and preened his ruffled plumage into order, the pair fell to at the feast, tearing off great fragments of their prey and devouring them hastily, lest the eagle should return, or the eagle’s yet more savage mate, and snatch the booty from them. Their object was to reduce it to a size that could be carried home conveniently to the nest. In this they were making swift progress when the banquet was interrupted. A long-limbed woodsman [page 17] in grey homespun, with a grizzled beard and twinkling grey-blue eyes, and a rifle over his shoulder, came suddenly into close view around a bend of the shore.

The two ospreys left their feast and flapped up into the top of a near-by pine tree. They knew the man, and knew him unoffending as far as they were concerned. He had been a near neighbour ever since their arrival from the south that spring, for his rough shack, roofed with sheets of whitish-yellow birch-bark, stood in full view of their nest and hardly two hundred paces from it. Furthermore, they were well accustomed to the sight of him in his canoe on the lake, where he was scarcely less assiduous a fisherman than themselves. But they were shy of him, nevertheless, and would not let him watch them at their feeding. They preferred to watch him instead, unafraid and quite unresentful, but mildly curious, as he strolled up to the mangled body of the fish and turned it over with the toe of his moccasined foot.

“Jee-hoshaphat!” he muttered admiringly. “Who’d ever a’ thought them there fish-hawks could a’ handled a togue ez big ez that? Some birds!”1

He waved a lean and hairy brown hand approvingly at the two ospreys in the pine-top, and then moved on with his loose-jointed stride up through the trees towards his shack. The birds sat watching him impassively, unwilling to resume their feast till he should be out of sight. And the big fish lay glittering in the sun, a staringly conspicuous object on the empty beach.

1 It must be understood that this expression is a polite euphemism for the backwoodsman’s too vigorous expletive.—C. G. D. R. [page 18]

But other eyes meanwhile—shrewd, savage, greedy eyes—had marked and coveted the alluring prize. The moment the woodsman disappeared around the nearest clump of firs, an immense black bear burst out of through the underbrush and came slouching down the beach towards the dead fish. He did not hurry—for who among the wild kindreds would be so bold as to interfere with him, the monarch of the wild?

He was within five or six feet of the prey. Then there was a sudden rush of wind above his head—harsh, rigid wings brushed confusingly across his face—and the torn body of the fish, snatched from under his very nose, was swept into the air. With a squeal of disappointed fury he made a lunge for it, but he was too late. The female osprey, fresher than her mate, had again intervened in time to save the prize, and lifted it beyond his reach.

Now, under ordinary circumstances the bear had no grudge against the ospreys. But this was an insult not to be borne. The fish had been left upon the beach, and he regarded it as his. To be robbed of his prey was the most intolerable of affronts; and there is no beast more tenacious than the bear in avenging any wrong to his personal dignity.

The osprey, weighed down by her heavy burden, flew low and slowly toward the nest. Her mate flew just above her, encouraging her with soft cries of Pip-pip-pip, pip-pip-pip, pip-pip-pip; while the bear galloped lumberingly beneath, his heart swelling with vindictive wrath. Hasten as he would, however, he soon lost sight of them; but he knew very well where the nest was, having seen it many times in his prowlings, [page 19] so he kept on, chewing his plans for vengeance. He would teach the presumptuous birds that his overlordship of the forest was not lightly to be flouted.

After four or five minutes of clambering over a tangle of rocks and windfalls he arrived at the foot of the naked pine trunk which bore the huge nest in its crotch, nearly fifty feet above the ground. He paused for a moment to glare up at it with wicked eyes. The two ospreys, apparently heedless of his presence and its dreadful menace, were busily tearing fragments of the fish into fine shreds and feeding their hungry nestlings—his fish, as the bear told himself, raging at their insolent self-confidence. He would claw the nest to pieces from beneath, and devour both the nestlings themselves and the prey which had been snatched from him. He reared himself against the trunk and began to climb—laboriously, because the trunk was too huge for a good grip, and with a loud rattling of claws upon the dry, resonant wood.

At that first ominous sound the ospreys took alarm. Peering both together over the edge of the nest, they realised at once the appalling peril—a peril beyond anything they had ever dreamed of. With sharp cries of rage and despair they swooped downwards and dashed madly upon their monstrous foe. First one and then the other, and sometimes both together, they struck him, buffering him about the face with their wings, stabbing at him in a frenzy with beak and talons. He could not strike back at them, but, on the other hand, they could make little impression upon his tough hide under its dense mat of fur. The utmost they could do [page 20] was to hamper and delay his progress a little. He shut his eyes and climbed on doggedly, intent upon his vengeance.

The woodsman, approaching his shack, was struck by that chorus of shrill cries, with a note in them which he had never heard before. From where he stood he could see the nest, but not the trunk below it. “Somethin’ wrong there!” he muttered, and hurried forward to get a better view. Pushing through a curtain of fir trees he saw the huge black form of the bear, now halfway up the trunk, and the devoted ospreys fighting madly, but in vain, to drive him back. His eyes twinkled with appreciation, and for half a minute or so he stood watching, while that shaggy shape of doom crept slowly upwards. “Some birds, sure, them fish-hawks!” he muttered finally, and raised his rifle.

As the flat crash of the heavy Winchester .38 startled the forest, the bear gave a grunting squawl, hung clawing for a moment, slithered downward a few feet, then fell clear out from the trunk and dropped with a thud upon the rock below. The frantic birds darted down after him, heedless of the sound of the rifle, and struck at him again and again. But in a moment or two they perceived that he was no longer anything more than a harmless mass of dead flesh and fur. Alighting beside him, they examined him curiously, as if wondering how they had done it. Then, filled with exultation over their victory, they both flew back to the nest and went on feeding their young. [page 21]

MUSTELA OF THE LONE HAND

It was in the very heart of the ancient wood, the forest primeval of the North, gloomy with the dark green, crowded ranks of fir and spruce and hemlock, and tangled with the huge windfalls of countless storm-torn winters. But now, at high noon of the glowing Northern summer, the gloom was pierced to its depths with shafts of radiant sun; the barred and chequered transparent brown shadows hummed with dancing flies; the warm air was alive with small, thin notes of chickadee and nuthatch, varied now and then by the impertinent scolding of the Canada jay; and the drowsing treetops steamed up an incense of balsamy fragrance in the heat. The ancient wilderness dreamed, stretched itself all open to the sun, and seemed to sigh with immeasurable content.

High up in the grey trunk of a half-dead forest giant was a round hole, the entrance to what had been the nest of a pair of big, red-headed, golden-winged woodpeckers, or “yellow-hammers.” The big woodpeckers had long since been dispossessed—the female, probably, caught and devoured, with her eggs, upon the nest. The dispossessor, and present tenant, was Mustela.

Framed in the blackness of the round hole was a sharp-muzzled, triangular, golden-brown face with high, pointed ears, looking out upon the world below with keen eyes in which a savage wildness and an alert [page 22] curiosity were incongruously mingled. Nothing that went on upon the dim ground far below, among the tangled trunks and windfalls, or in the sun-drenched tree-tops, escaped that restless and piercing gaze. But Mustela had well fed, and felt lazy, and this hour of noon was not his hunting hour; so the most unsuspecting red squirrel, gathering cones in a neighbouring pine, was insufficient to lure him from his rest, and the plumpest hare, waving its long, suspicious ears down among the ground shadows, only made him lick his thin lips and think what he would do later on in the afternoon, when he felt like it.

Presently, however, a figure came into view at sigh of which Mustela’s expression changed. His thin black lips wrinkled back in a soundless snarl, displaying the full length of his long, snow-white, deadly-sharp canines, and a red spark of hate smouldered in his bright eyes. But no less than his hate was his curiosity—a curiosity which is the most dangerous weakness of all Mustela’s tribe. Mustela’s pointed head stretched itself clear of the hole, in order to get a better look at the man who was passing below his tree.

A man was a rare sight in that remote and inaccessible section of the Northern wilderness. This particular man—a woodsman, a “timber-cruiser,” seeking out new and profitable areas for the work of the lumbermen—wore a flaming red-and-orange handkerchief loosely knotted about his brawny neck, and carried over his shoulder an axe whose bright blade flashed sharply whenever a ray of sunlight struck it. It was this flashing axe, and the blazing colour of the scarlet-and-orange kerchief, [page 23] that excited Mustela’s curiosity—so excited it, indeed, that he came clean out of the hole and circled the great trunk, clinging close and wide-legged like a squirrel, in order to keep the woodsman in view as he passed by.

Engrossed though he was in the interesting figure of the man, Mustela’s vigilance was still unsleeping. His amazingly quick ears at this moment caught a hushed hissing of wings in the air above his head. He did not stop to look up and investigate. Like a streak of ruddy light he flashed around the trunk and whisked back into his hole, and just as he vanished a magnificent long-winged goshawk, the king of all the falcons, swooping down from the blue, struck savagely with his clutching talons at the edge of the hole.

The quickness of Mustela was miraculous. Moreover, he was not content with escape. He wanted vengeance. Even in his lightning dive into his refuge he had managed to turn about, doubling on himself like an eel. And now, as those terrible talons gripped and clung for half a second to the edge of the hole, he snapped his teeth securely into the last joint of the longest talon and dragged it an inch or two in.

With a yelp of fury and surprise, the great falcon strove to lift himself into the air, pounding madly with his splendid wings and twisting himself about, and thrusting mightily with his free foot against the side of the hole. But he found himself held fast, as in a trap. Sagging back with all his weight, Mustela braced himself securely with all four feet and hung on, his whipcord sinews set like steel. He knew that if he [page 24] let go for an instant, to secure a better mouthful, his enemy would escape; so he just worried and chewed at the joint, satisfied with the punishment he was inflicting.

Meanwhile the woodsman, his attention drawn by that one sudden yelp of the falcon and by the prolonged and violent buffeting of wings, had turned back to see what was going on. Pausing at the foot of Mustela’s tree, he peered upwards with narrowed eyes. A slow smile wrinkled his weather-beaten face. He did not like hawks. For a moment or two he stood wondering what it was in the hole that could hold so powerful a bird. Whatever it was, he stood for it.

Being a dead shot with the revolver, he seldom troubled to carry a rifle in his “cruisings.” Drawing his long-barrelled “Smith and Wesson” from his belt, he took careful aim and fired. At the sound of the shot, the thing in the hole was startled and let go; and the great bird, turning once over slowly in the air, dropped to his feet with a feathery thud, its talons still contracting shudderingly. The woodsman glanced up, and there, framed in the dark of the hole, was the little yellow face of the Mustela, insatiably curious, snarling down upon him viciously.

“Gee,” muttered the woodsman, “I might hev knowed it was one o’ them pesky martens! Nobody else o’ that size ’ld hev the gall to tackle a duck-hawk!”

Now, the fur of Mustela, the pine-marten or American sable, is a fur of price; but the woodsman—subject, like most of his kind, to unexpected attacks of sentiment and imagination—felt that to shoot the defiant [page 25] little fighter would be like an act of treachery to an ally.

“Ye’re a pretty fighter, sonny,” said he, with a whimsical grin, “an’ ye may keep that yaller pelt o’ yourn, for all o’ me!”

Then he picked up the dead falcon, tied its claws together, slung it upon his axe, and strode off through the trees. He wanted to keep those splendid wings as a present for his girl in at the Settlements.

Highly satisfied with his victory over the mighty falcon—for which he took the full credit to himself—Mustela now retired to the bottom of his comfortable, moss-lined nest and curled himself up to sleep away the heat of the day. As the heat grew sultrier and drowsier through the still hours of early afternoon, there fell upon the forest a heavy silence, deepened rather than broken by the faint hum of the heat-loving flies. And the spicy scents of pine and spruce and tamarack steamed forth richly upon the moveless air.

When the shadows of the trunks began to lengthen, Mustela woke up, and he woke up hungry. Slipping out of his hole, he ran a little way down the trunk and then leapt, lightly and nimbly as a squirrel, into the branches of a big hemlock which grew close to his own tree. Here, in a crotch from which he commanded a good view beneath the foliage, he halted and stood motionless, peering about him for some sign of a likely quarry.

Poised thus, tense, erect and vigilant, Mustela was a picture of beauty swift and fierce. In colour he was of a rich golden brown, with a patch of brilliant yellow [page 26] covering throat and chest. His tail was long and bushy, to serve him as a balance in his long, squirrel-like leaps from tree to tree. His pointed ears were large and alert, to catch all the faint, elusive forest sounds. In length, being a specially fine specimen of his kind, he was perhaps a couple of inches over two feet. His body had all the lithe grace of a weasel, with something of the strength of his great-cousin and most dreaded foe, the fisher.

For a time nothing stirred. Then from a distance came, faint but shrill, the chirr-r-r-r of a red squirrel. Mustela’s discriminating ear located the sound at once. All energy on the instant, he darted towards it, springing from branch to branch with amazing speed and noiselessness.

The squirrel, noisy and imprudent after the manner of his tribe, was chattering fussily and bouncing about on his branch, excited over something best known to himself, when a darting, gold-brown shape of doom landed upon the other end of the branch, not half a dozen feet from him. With a screech of warning and terror, he bounded into the air, alighted on the trunk, and raced up it, with Mustela close upon his heels. Swift as he was—and everyone who has seen a red squirrel in a hurry knows how he can move—Mustela was swifter, and in about five seconds the little chatterer’s fate would have been sealed. But he knew what he was about. This was his own tree. Had it been otherwise, he would have sprung into another, and directed his desperate flight over the slenderest branches, where his enemy’s greater weight would be a hindrance. [page 27] As it was, he managed to gain his hole—just in time—and all that Mustela got was a little mouthful of fur from the tip of that vanishing red tail.

Very angry and disappointed, and hissing like a cat, Mustela jammed his savage face into the hole. He could see the squirrel crouched, with pounding and panic-stricken eyes, a few inches below him, just out of his reach. The hole was too small to admit his head. In a rage he tore at the edges with his powerful claws, but the wood was too hard for him to make any impression on it, and after half a minute of futile scratching, he gave up in disgust and raced off down the tree. A moment later the squirrel poked his head out and shrieked an effectual warning to every creature within earshot.

With that loud alarm shrilling in his ears, Mustela knew there would be no successful hunting for him till he could put himself beyond the range of it. He raced on, therefore, abashed by his failure, till the taunting sound faded in the distance. Then his bushy brown brush went up in the air again, and his wonted look of insolent, self-confidence returned. As it did not seem to be his lucky day for squirrels, he descended to earth and began quartering the ground for the fresh trail of a rabbit.

In that section of the forest where Mustela now found himself, the dark and scented tangle of spruce and balsam-fir was broken by patches of stony barren, clothed unevenly by thickets of stunted white birch, and silver-leaved quaking aspen, and wild sumach with its massive tufts of acrid, dark-crimson bloom. Here [page 28] the rabbit trails were abundant, and Mustela was not long in finding one fresh enough to offer him the prospect of a speedy kill. Swiftly and silently, nose to earth, he set himself to follow its intricate and apparently aimless windings, sure that he would come upon a rabbit at the end of it.

As it chanced, however, he never came to the end of that particular trail or set his teeth in the throat of that particular rabbit. In gliding past a bushy young fir tree, he happened to glance beneath it, and marked another of his tribe tearing the feathers from a new-slain grouse. The stranger was smaller and slighter than himself—a young female—quite possibly, indeed, his mate of a few months earlier in the season. Such considerations were less than nothing to Mustela, whose ferocious spirit knew neither gallantry, chivalry, nor mercy. With what seemed a single flashing leap he was upon her—or almost, for the slim female was no longer there. She had bounded away as lightly and instantaneously as if blown by the wind of his coming. She knew Mustela, and she knew it would be death to stay and do battle for her kill. Spitting with rage and fear, she fled from the spot, terrified lest he should pursue her and find the nest where her six precious kittens were concealed.

But Mustela was too hungry to be interested just then in mere slaughter for its own sake. He was feeling serious and practical. The grouse was a full-grown cock, plump and juicy, and when Mustela had devoured it his appetite was sated. But not so his blood-lust. After a hasty toilet he set out again, looking for something to kill. [page 29]

Crossing the belt of rocky ground, he emerged upon a flat tract of treeless barren covered with a dense growth of blueberry bushes about a foot in height. The bushes at this season were loaded with ripe fruit of a bright blue colour, and squatting among them was a big black bear, enjoying the banquet at his ease. Gathering the berries together wholesale with his great furry paws, he was cramming them into his mouth greedily, with little grunts and gurgles of delight, and the juicy fragments with which his snout and jaws were smeared gave his formidable face an absurdly childish look. To Mustela—when that insolent little animal flashed before him—he vouchsafed no more than a glance of good-natured contempt. For the rank and stringy flesh of a pine-marten he had no use at any time of a year, least of all in the season when the blueberries were ripe.

Mustela, however, was too discreet to pass within reach of one of those huge but nimble paws, lest the happy bear should grow playful under the stimulus of the blueberry juice. He turned aside to a judicious distance, and there, sitting up on his hindquarters like a rabbit, he proceeded to nibble, rather superciliously, a few of the choicest berries. He was not enthusiastic over vegetable food, but, just as a cat, will now and then eat grass, he liked at times a little corrective to his unvarying diet of flesh.

Having soon had enough of the blueberry patch, Mustela left it to the bear and turned back toward the deep of the forest, where he felt most at home. He went stealthily, following up the wind in order that his scent might not give warning of his approach. It was getting [page 30] near sunset by this time, and floods of pinky gold, washing across the open barrens, poured in along the ancient corridors of the forest, touching the sombre trunks with stains of tenderest rose. In this glowing colour Mustela, with his ruddy fur, moved almost invisible.

And, so moving, he came plump upon a big buck-rabbit squatting half asleep in the centre of a clump of pale green fern.

The rabbit bounded straight into the air, his big, childish eyes popping from his head with horror. Mustela’s leap was equally instantaneous, and it was unerring. He struck his victim in mid-air, and his fangs met deep in the rabbit’s throat. With a scream the rabbit fell backwards and came down with a muffled thump upon the ferns, with Mustela on top of him. There was a brief, thrashing struggle, and then Mustela, his forepaws upon the breast of his still quivering prey—several times larger and heavier than himself—lifted his bloodstained face and stared about him savagely, as if defying all the other prowlers of the forest to come and try to rob him of his prize.

Having eaten his fill, Mustela dragged the remnants of the carcase under a thick bush, defiled it so as to make it distasteful to other eaters of flesh, and scratched a lot of dead leaves and twigs over it till it was effectually hidden. As game was abundant at this season, and as he always preferred a fresh kill, he was not likely to want any more of that victim, but he hated the thought of any rival getting a profit from his prowess.

Mustela now turned his steps homeward, travelling more lazily, but with eyes, nose, and ears ever on the [page 31] alert for fresh quarry. Though his appetite was sated for some hours, he was as eager as ever for the hunt, for the fierce joy of the killing and the taste of the hot blood. But the Unseen Powers of the wilderness, ironic and impartial, decided just then that it was time for Mustela to be hunted in his turn.

If there was one creature above all others who could strike the fear of death into Mustela’s merciless soul, it was his great-cousin, the ferocious and implacable fisher. Of twice his weight and thrice his strength, and his full peer in swiftness and cunning, the fisher was Mustela’s nightmare, from whom there was no escape unless in the depths of some hole too narrow for the fisher’s powerful shoulders to get into. And at this moment there was the fisher’s grinning, black-muzzled mask crouched in the path before him, eyeing him with the sneer of certain triumph.

Mustela’s heart jumped into his throat as he flashed about and fled for his life—straightaway, alas, from his safe hole in the tree-top—and with the lightning dart of a striking rattler the fisher was after him.

Mustela had a start of perhaps twenty paces, and for a time he held his own. He dared no tricks, lest he should lose ground, for he knew his foe was as swift and as cunning as himself. But he knew himself stronger and more enduring than most of his tribe, and therefore he put his hope, for the most part, in his endurance. Moreover, there was always a chance that he might come upon some hole or crevice too narrow for his pursuer. Indeed, to a tough and indomitable spirit like Mustela’s, until his enemy’s fangs should finally lock [page 32] themselves in his throat, there would always seem to be a chance. One never could know which way the freakish Fates of the wilderness would cast their favour. On and on he raced, therefore, tearing up or down the long, sloping trunks of ancient windfalls, twisting like a golden snake through tangled thickets, springing in great airy leaps from trunk to rock, from rock to overhanging branch, in silence; and ever at his heels followed the relentless, grinning shape of his pursuer, gaining a little in the long leaps, but losing a little in the denser thickets, and so just about keeping his distance.

For all Mustela’s endurance, the end of that race, in all probability, would have been for him but one swift, screeching fight, and then the dark. But at this juncture the Fates woke up, peered ironically through the grey and ancient mosses of their hair and remembered some grudge against the fisher.

A moment later Mustela, just launching himself on a desperate leap, beheld in his path a huge hornets’ nest suspended from a branch near the ground. Well he knew, and respected, that terrible insect, the great black hornet with the cream-white stripes about its body. But it was too late to turn aside. He crashed against the grey papery sphere, tearing it from its cables, and flashed on, with half a dozen white-hot stings in his hindquarters prodding him to a fresh burst of speed. Swerving slightly, he dashed through a dense thicket of juniper scrub, hoping not only to scrape his fiery tormentors off, but at the same time to gain a little on his big pursuer. [page 33]

The fisher was at this stage not more than a dozen paces in the rear. He arrived, to his undoing, just as the outraged hornets poured out in a furiously humming swarm from their overturned nest. It was clear enough to them that the fisher was their assailant. With deadly unanimity they pounced upon him.

With a startled screech the fisher bounced aside and plunged for shelter. But he was too late. The great hornets were all over him. His ears and nostrils were black with them, his long fur was full of them, and his eyes, shut tight, were already a flaming anguish with the corroding poison of their stings. Frantically he burrowed his face down into the moss and through into the moist earth, and madly he clawed at his ears, crushing scores of his tormentors. But he could not crush out the venom which their long stings had injected. Finding it hopeless to free himself from their swarms, he tore madly through the underbrush, but blindly, crashing into trunks and rocks, heedless of everything but the fiery torture which enveloped him. Gradually the hornets fell away from him as he went, knowing that their vengeance was accomplished. At last, groping his way blindly into a crevice between two rocks, he thrust his head down into the moss, and there, a few days later, his swollen body was found by a foraging lynx. The lynx was hungry, but she only sniffed at the carcase and turned away with a growl of disappointment and suspicion. The carcase was too full of poison even for her not too discriminating palate.

Mustela, meanwhile, having the best and sharpest of reasons for not delaying in his flight, knew nothing of [page 34] the fate of his pursuer. He only became aware, after some minutes, that he was no longer pursued. Incredulous at first, he at length came to the conclusion that the fisher had been discouraged by his superior speed and endurance. His heart, though still pounding unduly, swelled with triumph. By way of precaution he made a long detour to come back to his nest, pounced upon and devoured a couple of plump deer-mice on the way, ran up his tree and slipped comfortably into his hole, and curled up to sleep with the feeling of a day well spent. He had fed full, he had robbed his fellows successfully, he had drunk the blood of his victims, he had outwitted or eluded his enemies. As for his friends, he had none—a fact which Mustela of the Lone Hand was of no concern whatever.

Now, as the summer waned, and the first keen touch of autumn set the wilderness aflame with the scarlet of maple and sumach, the pale gold of poplar and birch, Mustela, for all his abounding health and prosperous hunting, grew restless with a discontent which he could not understand. Of the coming winter he had no dread. He had passed through several winters, faring well when other prowlers less daring and expert had starved, and finding that deep nest of his in the old tree a snug refuge from the fiercest storms. But now—he knew not why—the nest grew irksome to him, and his familiar hunting-grounds distasteful. Even the eager hunt, the triumphant kill itself, had lost their zest. He forgot to kill except when he was hungry. A strange fever was [page 35] in his blood, a lust for wandering. And so, one wistful, softly-glowing day of Indian summer, when the violet light that bathed the forest was full of mystery and allurement, he set off on a journey. He had no thought of why he was going, or whither. Nor was he conscious of any haste. When hungry, he stopped to hunt and kill and feed. But he no longer cared to conceal the remnants of his kills, for he dimly realised that he would not be returning. If running waters crossed his path, he swam them. If broad lakes intervened, he skirted them. From time to time he became aware that others of his kind were moving with him, but each one furtive, silent, solitary, self-sufficing, like himself. He heeded them not, nor they him; but all, impelled by one urge which could but be blindly obeyed, kept drifting onward toward the west and north. At length, when the first snows began, Mustela stopped, in a forest not greatly different from that which he had left, but even wilder, denser, more unvisited by the foot of man. And here, the Wanderlust having suddenly left his blood, he found himself a new hold, lined it warm with moss and dry grasses, and resumed his hunting with all ancient zest.

Back in Mustela’s old hunting grounds a lonely trapper, finding no more golden sable in his snares, but only mink and lynx and fox, grumbled regretfully:

“The marten hev quit. We’ll see no more of ’em round these parts for another ten year.”

But he had no notion why they had quit, nor had anyone else—not even Mustela himself. [page 36]

MISHI

I

THE trail was not only steep and rough but at the same time slippery with the damp of spring, and the hunter, in that uncertain greyness of earliest dawn, had to pick his way with care. He was nearing the “timber line,” after a sharp climb of half a mile from the high but sheltered valley wherein he had made camp the night before. The woods, a monstrous jumble of rocks and trunks, matted shrubs and gnarled, sinister roots which clutched like tentacles for a grip to hold them against the tearing mountain winds, began to open out before him, and he caught glimpses of the naked mountain face, scarred with tremendous ravines and scrawled across with crooked, dizzy ledges. Far and high, the eternal snows had caught the full flood of the sunrise, and every soaring crag and pinnacle stood bathed in a glory of ineffable pink and saffron.

Merivale stopped, and stood watching, with an impulse to uncover his head, while the transfiguring splendour spread slowly down the steeps. In his frequent hunting-trips from the East he had seen many such miracles of sunrise among the western mountains, but familiarity had not dulled his sense to them, and he was never able to take the wonder lightly. But as he gazed the downward wash of that enchanted light suddenly [page 37] brought into view a shape which set Merivale’s pulses leaping and made him straightway forget the sunrise. On the giddy tip of a crag which jutted out from the steep, stood perched a stately mountain ram, his noble head, with its massive, curled horns sweeping backwards over his shoulders, high uplifted as he searched the waste for any sign of danger to his ewes. This was the splendid game in quest of which Merivale had come up from the foot-hills. He crept forward again, stealthily and swiftly, keeping well beneath the cover of the branches.

Suddenly there burst upon his ears a sound which brought him to an instant stop. It was not loud, but as it came muffled through the gloom there was something monstrous and terrifying about it. The sound came from somewhere above Merivale’s head and around to the left of where he crouched. It told him of a desperate struggle, of one of those tremendous battles to the death in which the beasts of the wild so rarely allow them themselves to become involved. There was a heavy crashing and trampling of underbrush, a clattering of stones displaced by mighty feet, mingled with great, straining grunts and woofs of raging effort.

“Grizzlies, fighting!” muttered Merivale with amazement, and stole noiselessly toward the sound, rifle in readiness, eager to catch a glimpse of so titanic a duel. Then the noise was varied by a single harsh and terrible scream, after which the sounds of struggle went on as before. But now Merivale understood. “No, not grizzlies,’ he said to himself, “a grizzly and a puma.” He had heard from the Indians of such tremendous [page 38] duels, but he had never expected to see one. His eyes shining with excitement, he hurried forward as quickly as he could without betraying himself. He quite forgot that in such a battle the great antagonists would be much too occupied to give heed to his approach. But it was slow work forcing his way through the rocky tangle, and the scene of the struggle proved to be farther away than he had guessed. Before he could reach the spot the noise of the battle came abruptly to an end, and there was no sound but a laboured, slobbery panting mixed with a hoarse whining which gave him an impression of mortal anguish. The next moment there came into view, lurching and staggering down the slope and blundering into the tree-trunks, a big grizzly, bleeding from head to haunch with ghastly wounds. His face was literally clawed to ribbons, and he was completely blinded. Moved by an impulse of mercy, Merivale lifted his rifle and send an explosive bullet through the sufferer’s spine. Then, very cautiously, he followed on up the grizzly’s trail to see how it fared with his antagonist.

Some thirty or forty yards farther on Merivale came upon the puma, lying dead and mangled in the trail, its ribs crushed in and one great fore-arm wrenched from its socket. It was a female—clearly a mother in full milk. Merivale’s sympathies were all with her, and as he stood looking own upon her and thought of the great fight she had put up against her huge adversary, he understood the whole situation. Clearly the wild mother had had her lair, and her helpless young, in some cleft of the rocks near by. She had seen the giant [page 39] Bear coming up the trail to the den. She had sprung down to meet him and join battle before he should get too near, and had given her life, a vain sacrifice, for her little ones.

Merivale, by this time, had lost interest in the game which he had come so far to seek. What he wanted was to find the puma kittens which, as he had heard, were easily tamed. They would be a more novel trophy than the finest head ever worn by a mountain ram. But first, after studying the dimensions of the dead mother, he went back and carefully considered the proportions of the grizzly, pondering till he had reconstructed the whole terrific combat which he had been so unfortunate as to miss the sight of. Then he set forth to seek the orphaned little ones.

The search was difficult in that precipitous jumble of rocks and undergrowth; but presently the trail of the dead mother, which he had lost on a patch of naked rock lately swept by a landslide, revealed itself to him again. Just then, from almost over his head came an outburst of small but angry spittings, followed by a cat-like cry of agony. Furious at the thought that some prowler had reached the defenceless nest ahead of him, Merivale sprang forward and swung himself recklessly up upon the ledge where the noises came from.

There, straight before him, in a shallow, sheltered cave, with the sunrise just flooding full into it, was the puma’s lair. The picture stamped itself in minutest detail on Merivale’s memory. One puma kitten, about the size of a common tabby, lay outstretched dead. A big red fox was just worrying a second to death, having [page 40] seized it too near the shoulders, and so failed to break its neck at the first snap. The third and last kitten was spitting and growling, and clawing manfully but futilely at the thick rich fur of the slaughterer. It was evident that the battle between the grizzly and the mother-puma had been watched by the cunning fox, who, as soon as he saw the result, had realised that it would now be quite safe for him to visit the undefended den and capture an easy prey.

Filled with wrath, but afraid to shoot lest he should kill the remaining kitten, Merivale bounded forward with a yell and aimed a vindictive kick at the assassin. Needless to say, he missed his mark. He just saved himself from falling, and staggered heavily against the wall of the den, while the fox, not stopping to argue the matter and present his own point of view, slipped over the ledge and vanished, an indignant red streak, through the bushes.

Merivale eased his feelings with a few vigorous curses, then turned his attention to the valiant little survivor, which had backed away against the rock wall and was spitting and growling bravely at the new foe. In colour, unlike its unmarked, grey-tawny mother, it was of a bright yellowish fawn variegated with dark brown, almost black, spots, and its long tail—just now curled round in front and twitching defiantly—was ringed like a racoon’s with the same dark shade.

Merivale, full of benevolence, reached out his hand to it gently, with soothing words such as he might have used to an angry but favoured cat. He got a vicious scratch from the furry baby claw. [page 41]

“Plucky little hellyun,” he muttered, approvingly, as he sucked the blood with his scrupulous care from the wounds, realizing that those baby claws might be far from hygienically innocent. Then, taking off his jacket, he dexterously caught the battling infant in its folds, rolling it over and over and swaddling down those rebellious claws securely, and leaving only the tiny black-and-pink muzzle free to spit its owner’s indomitable protests.

With a bit of twine from his pocket he lashed the squirming bundle safely, but with tender consideration for the comfort of its occupant, tucked it under his arm, and turned to retrace his steps down to his camp in the valley.

Then it suddenly occurred to him that by and by the fox would return to the den for his prey. Being absurdly angry with that fox, he took the trouble to carry off the two dead kittens, tying them together and slinging them to his belt. His intention was to throw them into the torrent which brawled down the valley, in order to make quire sure the presumptuous fox should not profit by his kill.

For about a day the spotted youngster was irreconcilable: but hunger, and Merivale’s tactful handling, soon brought it to terms. It took kindly to a diet of condensed milk, well diluted with warm water, and varied by a little raw rabbit or venison, it throve amazingly, and by the time Merivale was ready to break camp and move back to his ranch on the skirt of the foot-hills it was as tame as a house-cat, and as devoted to its master as a Sealyham terrier. [page 42]

II

Merivale treated his ranch in the western foot-hills—which was run the year round by a highly competent manager—chiefly as an excuse for a long summer’s holiday and hunting.

It was not till the end of September that he started back east for his home in Nova Scotia, taking his puma cub—no longer to be called a kitten—with him. The cub, now nearly six months old, was approaching his full stature, and was a peculiarly fine specimen of his race. Having by this time lost the dark markings which adorn all puma cubs at their birth, he was of a beautiful golden fawn over the upper parts and creamy white beneath, with a line of darker hue along his backbone and a brown tip to his long and powerful tail. His ears and nose were black, which gave a finish to his distinguished colouring. In length he was close upon seven feet, counting his two-foot-six of tail. His height at the shoulder was a little under two feet.

In his play—which was always gentle, thanks to Merivale’s wise training—he was the embodiment of lithe, swift strength. His savage inherited instincts having been lulled to sleep, or else never awakened, he was on the best of terms with all the dwellers upon the ranch, whether human or otherwise, the cattle alone expected. These latter could never endure the sight or the smell of him, and very early in his career he had learned to regard them as his implacable enemies and keep carefully out of their way. [page 43]

With the children on the ranch—there were four of them, belonging to the overseer—he was particularly popular, and to one, a long-legged little girl of about eleven, he was almost as devoted as to Merivale himself. She was alternately his playmate and his tyrant.

The name which Merivale had bestowed upon his pet was “Mishi,” the word by which the puma or panther is known among the Ojibway Indians. He would answer to this name as promptly as a well-trained dog. He would also come to heel for his master, like a dog. In fact, under Merivale’s training he acted much more like a dog than a cat, except that he would purr like an exaggerated cat when pleased, and wag his great tail in nervous jerks when annoyed.

The railway was a good half-day’s journey from Merivale’s ranch, and Mishi, who had never before seen a train, was terrified beyond measure by the windy snortings of the great transcontinental locomotive. He came near upsetting his master in his efforts to get between his legs for protection.

Merivale would have liked to have taken his favourite into the Pullman with him, but against any such proposal the guard, out of consideration for the feelings of nervous passengers, was obliged to set his face like steel. The young puma was therefore locked in an empty box-car, with a bed of clean straw, a supply of food and water, and his favourite plaything, a scratched and battered football, to console him.

But in spite of all this comfort, the long, long journey across the continent was a horror to the unwilling [page 44] traveller. The ceaseless jarring, swaying and roaring of the train set all his nerves on edge. He could only sleep when exhausted by hours of prowling up and down his narrow quarters. He would only eat—and then but a few hasty mouthfuls—when Merivale, at long intervals, came to pay him a visit during some extended halt of the train.

For the first time since his outburst of baby fury against the fox in his mountain den, he began to show signs of the savage temper inherited from his sires. He was homesick; he was desperately frightened; he was unspeakably lonely for his master. In revenge at last he fell upon the unoffending football, his old plaything, and with great pains and deliberation tore it to shreds.

But as luck would have it, Mishi’s journey was brought to an abrupt and unforeseen end. It was late in the night, and Merivale was sleeping soundly in his berth, when the train stopped at a lonely backwoods station in the wild country that lies between the Lower St. Lawrence and the northern boundary of New Brunswick. A ragged tramp, seeking to steal a ride, crept noiselessly along the side of the train away from the station lights, and found the box-car. He was an old train-hand and knew how to open it.

But as the door slid smoothly back that tramp got the shock of his life. Something huge and furry struck him with a force which sent him sprawling clean across the metals and over into the ditch. At the same instant the engine snorted fiercely—she was on an up grade—and the wheels began to turn with a groaning growl. [page 45]

Mishi went leaping off at top speed through the woods, double driven by the desire to find his master and by the terror of the panting, glaring locomotive. Deep in the spruce-woods he crouched at last, with pounding pulses, while the train, with Merivale asleep in his warm berth, thundered on steadily through the wilderness night.

III

As he lay there in the chill darkness, his nostrils drinking in the earthy scents of the wet moss and the balsamy fragrances of spruce and pine, faint ancestral memories began to stir in the young puma’s brain, and his pupils dilated as he peered with a king of savage expectancy through the shadows. He had long, long forgotten utterly the den upon the mountain-side, the caresses of his savage mother, and the last desperate battle with the marauding fox. But now dim, fleeting pictures of these things, quite uncomprehended, began to haunt and trouble him, and his long claws sheathed and unsheathed themselves in the damp moss. Suddenly realizing that he was ravenously hungry he glanced around on every side, expecting with confidence to see his accustomed rations ready to hand. It took him several minutes to convince himself that his expectation was a vain one. Truly, life had changed indeed. He would have to find his food for himself. He rose slowly, stretched himself, opened his jaws in a terrific yawn, and set forth on the novel quest. [page 46]

And now it was that Mishi’s inherited wood-lore fully woke up and came effectively to his aid. Instead of crashing his way through the bushes, careless as to who should hear his coming, he crept forward as noiselessly as a cat, crouching low and sniffing the night air for a scent which should promise good hunting.

Suddenly he stiffened in his tracks and stood rigid, with one paw uplifted. A little animal clearly visible to his eyes in spite of the darkness, was approaching. Resembling one of those big Jack-rabbits which Mishi had often chased (but never succeeded in catching) on the ranch, only much smaller, it came hopping along its runway, unconscious of danger. With an effort Mishi restrained himself from sprinting prematurely. Quivering with eagerness (for this was his first experience of real hunting) he waited till the rabbit was passing almost under his nose. Then out shot his great paw through the screening leafage—and the prize was his without a struggle, without so much as a squeak. Filled with elation at this easy success he made the sweetest meal of his life. As soon as his hunger was satisfied a great homesickness and longing for his master came over him. But this, of course, could not be allowed to interfere with his toilet. He licked his jaws and his paws scrupulously, washed his face and scratched his ears like a cat, then crept into the heart of the nearest thicket, curled himself up on the dry, aromatic spruce-needles and went to sleep. It was the first, real, sound, refreshing sleeping that he had enjoyed since leaving the ranch.

The sun was high when Mishi woke up, opening [page 47] puzzled eyes upon a world entirely novel to him. Interspersed among the dark green fir trees stood a few scattered maples, glowing crimson and scarlet in their autumn bravery. These patches of radiant colour held Mishi’s wandering attention for some moments till his thoughts turned to the more important question of breakfast. Instantly his whole manner and expression changed. He crouched with tense muscles, his eyes flamed and narrowed, his long white teeth showed themselves, and he began to creep noiselessly through the undergrowth, fully expecting another rabbit to come hopping into his path without delay. When this did not happen he began to grow angry. He had never been kept waiting for his breakfast before. There was something very wrong with this new world which he had been thrust into. Lifting up his voice he gave vent to a harsh and piercing scream, hoping that his master would hear and come to his rescue.

At the sound, with a sudden bewildering whirr-rr-rr of wings a covey of partridge sprang into the air, almost from under his nose, and went rocketing off through the trees. Mishi was so startled that he nearly turned a back somersault. Not lingering to investigate the alarming phenomenon he went racing off in the opposite direction like a frightened cat till his wind began to fail him. Then he huddled himself down behind a rock, craning his neck to peer around it nervously while he brooded over his wrongs. These however were presently forgotten under the promptings of his appetite, and he set forth again on his hungry prowl. Either by chance, or moved by a deep homing instinct, he turned his steps [page 48] westward. But suddenly from that direction came the long strident whistle of a train, wailing strangely over the tree-tops. At the sound, to him so fearful and so hateful, Mishi wheeled in his tracks and made off with more haste than dignity in the opposite direction. That dismal note stood to him for the cause for all his misfortunes.

At the bottom of his heart, however, the young puma, as he had shown in babyhood, was valiant and high mettled. It was only the unknown, the uncomprehended, that held terrors for him. And he was not one to dwell upon his fears. In a few moments he had forgotten them all in the excitement of sniffing at an absolutely fresh rabbit track. The warm scent reminded him of his last meal. He proceeded to follow up the trail with all stealth, little guessing that the rabbit, its eyes bulging with terror, was already hundreds of yards away and still fleeing. It had never dreamed that its familiar woodlands could harbour such an apparition of doom as this great, tawny, leaping monster with the eyes of pale flame.

It was not in Mishi’s instinct to follow a trail long by the scent. Speedily growing discouraged, he hid himself beside the runway hoping that another rabbit would come along. When he had lain there motionless for perhaps ten minutes, his tawny colour blending perfectly with his surroundings, a couple of brown woodmice emerged from their holes and began to scurry playfully hither and thither among the fir needles. Mishi never so much as twitched a whisker as he watched them from the corner of his narrowed eyes. At last they [page 49] came within reach. Out flashed his swift paw, and crushed them both together. They made hardly a mouthful, but it was a tasty one; and Mishi settled down again to watch hopefully for more.

A few minutes later a red squirrel, one of the quickest-witted and most inquisitive of all creatures of the wild, peering down through the branches, thought that he detected something strange in the shadowy, motionless figure far below. Nearer and nearer, circling noiselessly down the trunk, he crept, his big bright eyes ablaze with curiosity, till he was within a couple of yards of Mishi’s tail. Then and not till then did he catch the glint of Mishi’s narrowed eyes fixed upon him, and realise that the shadowy shape was something alive, a new and terrible monster. With a chattering shriek of wrath and fear he raced up the trunk again, and, dancing as if on wires in excitement, began to shrill out his warning to all forest dwellers.

In two seconds Mishi was up the tree, gaining the lower branches in one tremendous spring, and scrambling onwards like a cat, with a loud rattling of claws. But already the squirrel was several trees away, leaping from bough to bough and shrieking the alarm as he fled. It was taken up by every other squirrel within hearing, and by a couple of impudent blue jays who came fluttering over Mishi’s head with screams of insult and defiance. Realising well enough that there could be no more secrecy for him in this neighbourhood, Mishi dropped to the ground and made off at a leisurely lope, pretending to ignore his tormentors. The latter followed him for nearly half a mile till at last, satisfied with [page 50] their triumph, they returned to their autumn business of gathering beechnuts.

The wanderer was by this time much too ravenous to brood over his discomfiture. He must find something to eat. Resuming his stealthy prowl he presently came to the edge of a little river, its gold-brown current gleaming and flashing in the sun. He was just about to creep down to it and quench his thirst when he saw a small blackish-brown creature, about the length of a rabbit, but shorter in the legs and very slim, emerge from the water and crawl forth upon the bank, dragging after it a glistening trout almost as big as itself.

Mishi had never seen a mink before, but he felt sure the little black animal would serve very well for his breakfast.

In this, however, he was mistaken. He little knew the mink’s elusiveness. The mighty spring with which he launched himself through the screen of leafage was lightning swift—but when he landed the mink had vanished as completely as a burst bubble. But the fish was there; and, wasting no time in vain surprise, he bolted it head and tail. It was hardly a full meal for a beast of his inches, but it was enough to put him in a better humour with his fate.

He followed up on the shore for, perhaps, a quarter of a mile, half expecting to find another fish. Then, coming to a spot where the stream threaded with musical clamour through a line of boulders which afforded him a bridge, he crossed and crept again into the woods.

Almost immediately he came upon a well-beaten trail—a path which, as his nose promptly informed him, [page 51] had been made by the feet of man. Mishi’s heart rose at the sight. Men, to him, meant friends and food and caresses, and above all, Merivale. With high hopes he trotted on up the path, till he emerged from the woods upon the edge of a wide, sunny clearing. Near the centre of the clearing stood a log cabin, flanked by a barn and a long, low shed. At one end of the cabin a clump of tall sunflowers flamed golden in the radiant air. From the cabin chimney smoke was rising, and a most hospitable smell of pork and beans greeted Mishi’s nostrils. He bounded forward joyously, thinking all his troubles at an end.

But at this very instant a big red cock, scratching on the dungheap beside the barn, caught sight of the strange tawny shape emerging from the woods.

“Krree-ee-ee!” he shrilled at the top of his piercing voice, and “Kwit-kwit-kwit-kree-ee-ee!” his signal of most urgent warning and alarm. With squawks of fright all his hens scurried to cover—though he himself, consumed with curiosity, valiantly stood his ground. A black-and-white cur popped round the corner of the barn, stared for a couple of seconds as if unable to believe his eyes, then raced, ki-yi-ing with horror, towards the cabin door, his tail between his legs.

The door flew open, and a stout woman, in a grey, homespun petticoat, with a red handkerchief twisted over her hair and a bright tin pan in her hands, peered forth to see what all the noise was about.

“My lands!” she ejaculated, dropping the pan with a loud clatter, and jumped back into the kitchen again, slamming the door in the very face of the black-and- white [page 42 cur, who thereupon fled around behind the house with a yelp of despair.

This was by no means the kind of welcome which Mishi had been expecting, and he paused for a moment, feeling bewildered and rebuffed. Then a new whiff of pork and beans came to his nostrils, and he started forward again, but now more diffidently. He felt no longer any hope of finding his master in that inhospitable cabin.

Fortunately for him, he was still at some distance from the cabin when the small window beside the door was thrown open, and the stout woman appeared at it with her goodman’s shot-gun. She was a woman of resource, and knew that her husband always kept the gun loaded—though how it was loaded she had never troubled to inquire. Had she been fully aware of the fact that it was loaded for partridges the knowledge would have made no difference to her action.

In her eyes a gun was a gun, and a load was a load, whether bullet, slugs, or snipe-shot. She thrust the muzzle out through the window, pointing it vaguely at Mishi, who looked at her in mild appeal, and then lay down and rolled to show his friendliness. It was an accomplishment which, in the good old days, had never failed to win approval and caresses. But it was quite lost on the stout woman at the window. She lifted the butt of the gun to her shoulder as she had seen her husband do, and pulled the trigger.

The recoil of the loosely-held weapon so staggered her that she fell backwards over a tub of water, upset a bench with a pile of dishes on it, and screeched in [page 53] terror, thinking the gun had exploded and probably killed her.

By some miracle—for the stout woman had made no attempt to aim—a couple of flying pellets grazed one of Mishi’s forepaws as it waved conciliatorily in the air. At the crashing report, the clatter, the shriek, and the burning sting of the wound in his paw, Mishi bounced to his feet and went bounding away into the kindly shelter of the forest, his heart bursting with injury.

The black-and-white cur, reappearing from behind the cabin, capered across the barn-yard with a peal of triumphant yelps, proclaiming that he, himself, had put the dread intruder to flight; while the red cock, after eyeing the futile little animal with scorn, flew up to the top of the wood-pile and crowed.

The sting in Mishi’s wounded foot, as well as in his wounded feelings, now kept him going, not fast but steadily, till he had put many miles between him and the scene of his rebuff.

He crossed several rippling, amber streams, overhung with golden birches, and the wax vermilion clusters of the rowanberries.

Not till about sunset did he think about hunting again, and settle down to a stealthy prowl; and in the meantime, sharp eyes, wary and hostile or shy and horrified, all unknown to him had marked his progress. Fox and weasel, mink and woodchuck and tuft-eared lynx, all had seen him, and recognised a new and terrible master in the wilderness; and even the indifferent porcupine, secure in his armour of deadly quills, had paused in his gnawing at the hemlock-bark and quivered with [page 54] apprehension as the tawny shape went by. Some ancient instinct warned him that here was a foe who might be clever enough to undo him.

But to Mishi’s untrained senses the bright forest, all this while, had seemed quite empty. When he hid himself, however, it soon grew populous again, and faint unfamiliar sounds began to make themselves heard. Not yet being woods-wise he paid no heed to them. But suddenly his attention was caught by a noise which excited him at once, though he knew not why.

It was a confused sound of tramplings and stampings and snortings, with now and then a flat clatter as of sticks beaten against each other.

With a strange thrill in his nerves he crept forward and presently found himself starting out, through fringing bushes, upon a duel between two red bucks in the centre of a little forest glade. It was rutting season, and the high-antlered bucks were fighting for the possession of three plump, mild-eyed does, who, quite indifferent to the result, were calmly pasturing at the farther end of the glade.

For perhaps a minute Mishi watched the fight with a wondering interest, heightened perhaps by the first stirrings of the mating fever in his own veins. Then hunger overcame all other emotions. With a mighty leap he landed upon the shoulder of the nearest buck, bearing him to the ground. At the same time, taught by generations of deer-killing ancestors, he clutched the victim’s head with one great paw and twisted it back so violently as to dislocate the neck. With eyes bulging from their heads in horror the remaining buck and the [page 55] does crashed off through the woods, leaving the dreadful stranger to his meal.

IV