[handwritten: May Neal

15 Avalon Court

Regina]

[illustration]

Winged Moccasins

to~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Winged Words

[illustration]

by Margaret Complin

I wish to thank the Editors whose encouragement made this booklet possible.

[unnumbered page]

[illustration: Courtesy of the Valley Echo]

THE WESTERN PRINTERS ASSOCIATION, LTD.

REGINA, SASKATCHEWAN

[unnumbered page]

1837 | Prairie Mails | 1937 |

With letters for the Factor

Up the trail a Saulteau sped

On moccasined feet past the coulee rim

Where deer and buffalo fed.

Red River carts with pemmican

And pelts creaked down the trail

Where Grey Eagle ran like lightning

With the Great White Mother’s Mail.

Across the wind-swept airfield

The beacon’s guiding light

Shines past the throbbing mail plane

And stretches out into the night.

The pilot opens the throttle …

Through star-shot clouds they sail—

Rushing down the silent sky-ways

With King George’s Prairie Mail.

FLOREAT [illustration] REGINA

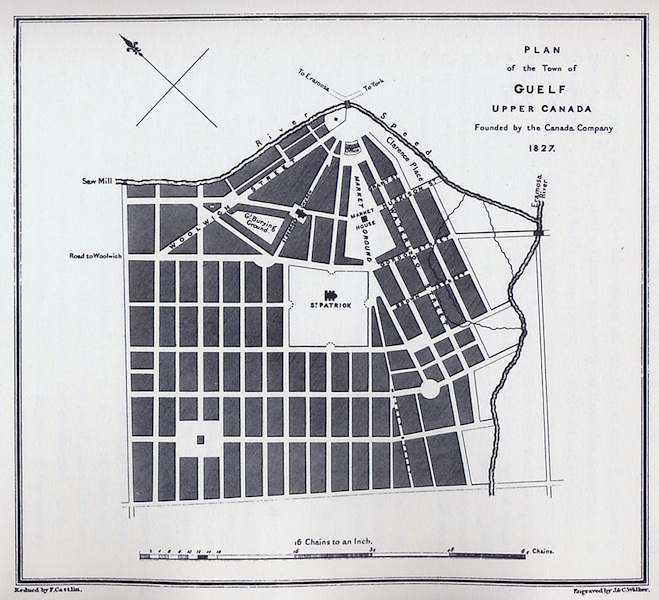

REGINA, the capital of Saskatchewan, primarily owed its existence to the engineers and surveyors who united East and West by the great transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway. When the southern route was finally decided upon for the main line it became necessary to appoint a new capital for the North West Territories, as Battleford, which in 1877 had taken the place of the provisional capital Livingstone, was not on the railway.

Fort Qu’Appelle, long the frontier of civilization in the West, and Troy, or South Qu’Appelle, where a party of Easterners had taken up land around a common railway centre, were bitter rivals for the honour. However, the Government of Sir John A. Macdonald, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Lieutenant Governor of the Territories finally chose for the site of the future capital, which was also to be headquarters of both the North West Mounted Police and the Department of Indian Affairs, a treeless, windswept site near the well-worn trail between Fort Qu’Appelle, the Moose Jaw Bone, and the Hudson’s Bay Company fort at Wood Mountain. Because of its proximity to the precious, if muddy water of Wascana or Pile O’Bones Creek, the place had long been a favourite camping-ground of fur traders and of Indian and halfbreed buffalo hunters. [unnumbered page]

The tent of Lieutenant Governor Dewdney was pitched on the bank of the creek near the railway bridge, close to where Lutheran College stands today; and a prominent old-timer recently stated that the proclamation of June 30th, 1882, setting aside the Regina Reserve, was likely made conspicuous by being fixed to the horns of one of the countless buffalo skulls literally covering the prairie on every side.

Many difficulties appear to have been encountered in the selection of a name for the embryo capital. The Archives of the Legislative Library of Saskatchewan contain two interesting letters on the subject from the Marquis of Lorne, who writes that the name Regina was chosen by the Princess Louise in honour of Queen Victoria, in response to a telegram received while they were at lunch on the Terrace at Quebec. The christening ceremony of the infant Regina took place when the railway reached Pile O’Bones Creek at nine o’clock on the morning of July 23rd, 1882. Judge Johnson of Montreal proposed the toast—“Success to Regina, Queen City of the Plains,” in the presence of the Lieutenant Governor and Mrs. Dewdney and many distinguished officials of the Dominion Government, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian Pacific Railway. A band of Indians from Piapot’s Reserve,—worthy of being immortalized by the brush of Catlin or Paul Kane—who had doubtless learned of the arrival of the white man’s “Fire Waggon” through moccasin telegraph, watched the ceremony wonderingly.

From time immemorial the level, grassy, Oskana or Many Bones Plain was a favourite feeding ground of countless buffalo. The little creek at Pilot Butte, six miles east of Regina, where the herds “wallowed in the black ooze of the sloughs,” has been dammed up to provide water for railway engines, but the high butte on which the sentry was posted to report the approach of the herd still overlooks the prairie, and it is possibly the conical hill mentioned in the Journal of D. W. Harmon. To the north-west of the present city of Regina, opposite a famous pound near the site of what is still known as the Old Crossing, superstitious Indian hunters, believing that the buffalo were loath to forsake the bones of their kindred, erected a large pile of the bones thrown aside after the flesh had been made into pemmican. Tradition says that even as late as 1865 this pile was six feet high and forty feet at the base. Isaac Cowie, a clerk of the Hudson’s Bay at Fort Qu’Appelle, tells of a Cree Indian who perished near Pile O’Bones during the Christmas season of 1867; later in the winter Cowie only saved himself from a similar fate by burrowing under buffalo robes and blankets.

The first settler in the Regina district was Edward Carss, who homesteaded in September, 1881, at the junction of the Qu’Appelle River and Wascana or Pile O’Bones Creek. On May 24th, 1882, an advance party of settlers arrived at the Old Crossing; another party arrived on June 10th and built sod shanties on the banks of the Creek. Tents of later pioneers dotted the prairie in the vicinity of the railway bridge, near the tent of Governor Dewdney, where it was supposed the town would be located. But the all-powerful Canadian Pacific built their station, which of course located the town, two miles east of this site, and crowds of disappointed squatters moved to “The Gore,” as the triangular piece of ground on South Railway Street was named. Mowat Bros., who were already operating a store in opposition to the Hudson’s Bay at Fort Qu’Appelle, were the first to open for business on the new site, and the “hotelkeeper pegged his tent wherever he could dispose of beef, bacon, bunks and beer.” A large packing box served as the makeshift postoffice, and the storekeeper whose turn it was to allow the box to stand inside the [unnumbered page] door of his tent acted as postmaster. The first religious service in Regina was held in the large, striped restaurant tent of Gowanlock, who three years later was a victim of the Frog Lake massacre. Regina Mary Rowell, the first native Reginan, was born on December 13th, 1882.

It is interesting to note the prices paid by the pioneers for the necessities of life. A barrel of water cost from fifty cents to a dollar; bread was twenty-five cents a loaf; wood, usually brought from the bluffs around Edenwold, or sold by Indians with Red River carts, cost twelve dollars a load; and coal, which was very difficult to procure, cost twenty-five dollars a ton. The wages of carpenters, blacksmiths, teamsters and all other workers were correspondingly high.

In March, 1883, an Order-in-Council removed the Territorial capital from Battleford to Regina, which was gazetted as the new capital the following month, and made an incorporated town in December. It is not on record, however, that either Battleford, the disinherited, or Winnipeg, still suffering from the effects of the break of the land boom, showed any feelings of cordiality towards their young sister, and the newspapers of both places published many derisive editorials on the ambitious young town. Regina, nevertheless, had a ready champion in Nicholas Flood Davin, the founder of The Regina Leader. The name of this brilliant Irishman, who in pioneer days had the vision to write: “I am a North West man, and I think the cultivation of taste and imagination as important as the raising of grain,” is still remembered with affectionate pride.

Frame houses, churches and more or less pretentions public buildings soon took the place of the tents of the pioneers; arrangements made for digging a good town well were doubtless expedited when it was discovered that an Indian woman had been drowned in the well at the station; and Regina was reported by a correspondent of The London Times as “Rivalling even the usual spread made by prairie towns.”

The first Government House, built in 1883 and demolished in 1910, was a long, low “glorified bungalow” constructed from two ready-made buildings shipped from British Columbia, and built into one and painted a reddish colour at Regina. The building was not only the official residence of the Honourable Edgar Dewdney, but also housed various Departments of the Government. Other public buildings were also long used for diverse purposes, notably the Indian Offices on Dewdney Avenue where the first Legislative Library found a precarious shelter. Flimsy shelves sagged under the weight of the books; overhead was the office of the Government Bacteriologist, and beneath were rats, guinea pigs and other animals necessary in his experiments. One is hardly surprised that the Librarian rejoiced when the cyclone of 1912 “perhaps providentially put it out of business.”

In March, 1855, the misguided Half-Breeds of northern Saskatchewan rose in rebellion, and the horrors of an Indian uprising were also feared. The final scene in this tragedy took place in Regina, when Louis Riel, though ably defended by François Xavier Lemieux, a young lawyer from Quebec, was sentenced to death by Judge Hugh Richardson. Poundmaker, Big Bear, and other unfortunate Indian chiefs were also tried at Regina.

“The point where the railway crosses Pile O’Bones Creek” was certainly not chosen as the site of the capital of the Territories because of any beauty of situation, and it was not long before tree-lovers among the Pioneers instituted a tree-planting campaign. We read in the yellowing pages of the [unnumbered page] earliest history of Regina that “On the 7th of May, 1886, the Lieutenant Governor, the Town Council, and interested citizens, made a big Arbour Day … and planted a suitable variety of trees.” The Headquarters of the North West Mounted Police had been laid out by Inspector—afterwards Sir Sam—Steele, on the homestead of Mr. George Moffat, two miles west of the station, but nothing had ever been done towards improving the environment of the portable huts standing as though at attention around the desolate Barrack Square, and many Reginans of 1886 were “highly indignant” when Commissioner Herchmer made roads and paths and fenced off the Square. He also brought poplars by Police teams from the Qu’Appelle Valley, and imported Manitoba maples from Winnipeg. At a later date Governor Forget brought fir trees from Banff to beautify the grounds of new Government House.

Possibly Regina was the last place in the West in which pemmican was made, for that invaluable food was included in the rations of Mounted Police sent to the Yukon during the Bonanza Creek gold rush of 1896. The drying, pounding and packing of this synthetic pemmican, made of beef, not buffalo, was under the direction of the famous Half-Breed buffalo hunter and interpreter Peter Hourie and his wife.

In the historic year 1905 an Act of the Dominion Parliament divided the Territories, and Regina was later made the capital of the newly created Province of Saskatchewan. In 1909 Earl Grey, Governor General of Canada, laid the corner-stone of the beautiful Legislative Buildings—“an enduring monument to the pioneers of the Province.” Many treasures of great historical value are in the Library, notably the table around which the Fathers of Confederation sat during the Quebec Conference of 1864.

An illustrated booklet issued by the Regina Board of Trade in 1911 gives proof conclusive of the commercial and financial importance of the city described as “the undisputed business centre of the wheat fields of Canada.” Land values in those boom days doubled and trebled with uncanny rapidity, and banks, trust companies and real estate offices were built “where two years ago the undulating prairie grass waved in the breeze.”

On the 30th of June, 1912, Regina suffered from the greatest tragedy in its history—the most terrific cyclone that has ever been experienced in any part of Canada. Before the work of restoration was completed came the Great War, when over two thousand volunteers from Regina were wounded, and over five hundred gave their lives.

The spirit of the pioneers is still alive in the Regina of today, and the arrival of the settlers of fifty years ago was commemorated by the World’s Grain Exhibition and Conference of 1933. — Canadian Geographical Journal. [unnumbered page]

[illustration]

Lawrence

Herchmer

The naming of a school in the city of Regina “The Herchmer School” after Lawrence Herchmer, Commissioner of the North West Mounted Police from 1886 to 1900, should appeal to the younger generation who can in imagination “Ride on the plain with the buffalo herd, or camp with the Indian brave.”

Still more, however, should it waken memories in that older generation who realizes that we must make a point of perpetuating the names of the Builders of the West, else the old names will die as the new names grow—already we have too many names all too intermittently remembered.

Seldom has anyone had a more picturesque setting than had Herchmer on that stage in whose drama he was to play so leading a part for nearly fourteen years … In the distance was the tragically pathetic background of the people of an ancient civilization passing away from the land given them by the Great Spirit. There was the marvel of that keystone of Confederation, possible odds. The horrors of the Riel Rebellion of 1885 were still fresh in everyone’s memory … In the centre of the stage was that ‘Silent Force’ the North West Mounted Police.

Romance, too, was not lacking in the history of the leading actor in this drama of the West. Doubtless the personal bravery, the untemporizing obstinacy, the rectitude, and the devotion to duty marking Herchmer’s character were all the result of events that began generations before his advent on this world’s stage. He belonged by right of birth to that proud Canadian aristocracy, the United Empire Loyalists. Some years previous to the American Revolution numerous families, attracted by the beauty and fertility of the country adjoining the Hudson River, emigrated to the Mohawk Valley in the State of New York, near the headquarters of that great Indian League so faithful to the British, known as “The Five Nations,” and the ancestors of Lawrence Herchmer settled near Little Falls an what is now known as Herkimer, in Herkimer County. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775 Nicholas Herkimer, cousin of the Commissioner’s grandfather, joined the revolutionists, and became one of their most famous generals. The other branch of the family remained loyal to King and Flag, and about 1783, the date of the Treaty of Separation, left their homes for the vast, unknown wilderness of Upper Canada. Grants of land were given to these brave Loyalists, and Herchmer’s grandfather settled where the city of Kingston now [unnumbered page] stands. William Herchmer, his son, father of Lawrence, was educated at Oxford, and before returning to Canada married a Miss Turner, niece of the famous English painter. Eventually he brought his English bride to his home in Kingston, where he was for many years Rector of St. George’s Church.

Lawrence Herchmer, the eldest son, was born at Henley-on-Thames, England, and received much of his education in that country. When only 17 he obtained a Commission in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, serving in both India and Ireland. Five years later, on the death of his father, he resigned, and for a few years lived in Kingston. In 1864 he married Helen Mary Sherwood, daughter of the first Attorney General of Upper Canada. At a later date he served as Commisariat Officer with the Boundary Commission, and afterwards in the Department of Indian Affairs at Birtle, Manitoba.

In 1886 Sir John A. Macdonald, with approval of Mr. Fred White, Comtroller, appointed Herchmer Commissioner of the North West Mounted Police, and on April 1st of that year he arrived at “the portable construction set-up on the treeless mire of Regina” that formed the Headquarters of the Police at that date. This Force, over which he was to rule with such tireless efficiency for thirteen years, had been created by Sir John in 1873, and consisted originally of only three hundred men, whose duties were to patrol the frontier, collect customs, prevent whisky-smuggling, protect both the pioneers and Indians from hordes of traders, adventurers, and outlaws from the United States; and later to guard the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway across the Indian-ridden plains of the Territories. . . .

The Force was to have been know as the Mounted Rifles, but in deference to objections from Washington the name was changed to North West Mounted Police. The official records of French, Walsh, Macleod, Irvine, Macdonnell, Steele—to mention but a bare half-dozen of the earlier officers—as well as the sketches of Julien, and canvasses of C. W. Russell, give a graphic picture of old days in the Territories.

The task of reorganizing for which Herchmer had been appointed was a strenuous one, and to it he applied almost incredible energy, and genius for the minutest detail. The West was nervously reacting from its experiences in that last tragedy of the Red Man’s losing fight against civilization known as the Saskatchewan Rebellion. Both officers and men of the Police were suffering from the toil and strain of those anxious days; and were indignantly resentful of the unjust and ignorant criticisms of Eastern politicians. The hasty enlistment by the Government of six hundred undisciplined recruits had so complicated matters that there had been insubordination and mutiny at Edmonton and other posts. It is to Herchmer’s undying credit that he succeeded in bringing order of all this chaos; eventually inaugurating the ‘Golden Age’ of the Force.

There was, of course, much opposition to his methods … but Herchmer’s policy, founded on the firm rock of comprehension of the needs of his Force remained unshaken.

With changing conditions in the West the problems to be faced by the Commissioner differed from those of his predecessors. Though whisky-smuggling was still the despair of the Police, the fluid was no longer shipped in tin Bibles, or egg crates marked “Fragile,” neither could the country continue to be described as “a world divested of the ten commandments.” One of the chief duties of his men was to protect the thousands of homesteaders [unnumbered page] coming into the country from prairie fires and cattle-stealers. Then, too, smouldering ashes of discontent among the Indians were liable to break into flame, as in the case of the Cree, Almighty Voice, who shot Sergeant Colebrook near Kinistino. In Herchmer’s time the Police also extended their activities into the Yukon; twenty picked officers and men being sent to Fort Cudahy in 1895, and somewhat later into the inhospitable wilderness of the Arctic Circle.

The improvements he effected in the lot of his men were equally far-reaching. He established canteens where they ‘could have beer at home, rather than whisky abroad’; encouraged shooting competitions; persuaded the Comptroller to build modern barracks instead of portable tin huts; and, most important of all, secured the benefit of pensions for his men. “In naming a school after my Father,” writes his daughter in 1930, “you have remembered him in the way he would like best; he was always so keen in trying to better people’s conditions.”

It would be a mistake to discuss the vexed question of the injustice that clouded the last fifteen years of the Commissioner’s life. To his friends Herchmer needs no vindication, but he who reads between the lines will find a sympathetic explanation in the chapter entitled “Reward” in Longstreth’s The Silent Force.

The Last Post for this gallant soldier was sounded far from the prairie land he served so faithfully—“Remember Lord Thy disappointed dead” might well be a fitting epitaph for his grave beside the misty Pacific.

The work of the Force he “raised from perilous depths to glittering heights” is still a factor in the country to which Herchmer contributed so much. To those who ask what he accomplished one quotes: “If thou seekest his monument look around.”—The Leader-Post.

Calling Valley of the [illustration]

Crees and Buffalo

The waves of the Fishing Lakes glisten and ripple in the sunlight like watered silk; the wayward little Qu’Appelle river wanders sinuously from lake to lake of the Calling Valley. But fragrant smoke from teepee fires no longer ascends spirally into the clear air; no Metis or Indian Buffalo hunters bring pemmican and peltries to Fort Qu’Appelle; and the red ensign, with the historic letters H B C on the fly, no longer flutters expectantly from the flagpole on the crumbling little building which is all that now remains to tell of that dead past when “there were no fixed habitations of man on British territory between the fort and the Rocky Mountains to the west.”

It is probable that the earliest British traders to establish permanent posts on the Assiniboine or Upper Red river and its affluents, the Qu’Appelle and the Mouse or Souris river, came to the country about 1780. Fort Esperance [unnumbered page], the first post of the Qu’Appelle of which any record appears to be available, was built in 1783 by a Nor’wester, Robert Grant. “There is evidence that the Hudson’s Bay also had sent men from the Assiniboine to the Missouri about this time,” says Lawrence J. Burpee in “The Search for the Western Sea,” but neither names nor dates are now extant.” Brandon House on the Assiniboine, about seventeen miles below the city of Brandon, was built by the Company in 1794. Two years later the post at Portage la Prairie (the site of La Verendrye’s Fort La Reine) was established. According to Dr. Bryce it was about 1799 that the Company took possession of the Assiniboine district.

The Swan River country, which later became one of the most important districts of the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land, is associated with the name of Daniel Harmon, the Nor’wester, who arrived in the district in 1800. Harmon spent over three years at Fort Alexandria and various posts in Peche (probably what we today call the Quill Lakes). On March 1st he was at Last Mountain Lake, and by Sunday, 11th, had reached the banks of Cata buy se pu (the River that Calls). “The Indians who reside in the large plains,” he says, “are the most independent, and appear to be the most contented and happy people on the face of the earth.”

After the amalgamation of the companies in 1821, the most serious competition came from American traders and free traders who had followed the buffalo herds in their gradual recession to new feeding grounds in the west. In 1831 the Council of the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land decided that “in order to protect the trade of Assiniboines and Crees from American opposition on the Missouri, a new post be established at or in the neighbourhood of Beaver Creek, to be called Fort Ellice.” The next year Fort Ellice was added to the Swan River district.

The first Hudson’s Bay Company fort on the Qu’Appelle lakes is said to have been an outpost of Fort Ellice, but no record of its establishment is to be found in any provincial records available at Regina. In 1858 Qu’Appelle Fort was visited by Professor Youle Hind, who says: “At one o’clock we reached our destination, a small trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which, having first been situated on the Qu’Appelle lakes, is known by that name. Pratt, a missionary of the Church of England, a pure Stoney, lived there.”

Palliser, in his report of 1858-61, says: “The Qu’Appelle lakes may be considered the most western portion of the territory east of the Rocky Mountains into which the Hudson’s Bay Company trade; westward of this is unknown, and the whole country is untravelled by the white man.” Qu’Appelle Fort was at this time, according to Dr. Hector, situated sixteen or eighteen miles south of what is today the town of Fort Qu’Appelle. Remains of a post, once supposed to have been an establishment of the Company, can be traced south of McLean, but it is likely that they mark the site of a post once operated by Metis free traders. In a little white cottage perched on the high hills overlooking Lebret and Mission Lake, there lives an old buffalo hunter, Johnny Blondeau, who claims to be able to point out the site of old Qu’Appelle Fort. His father was one of the Hudson’s Bay men who built the post, and Blondeau lived there perhaps eighty years ago. He can also tell stirring tales of the days when Sitting Bull and his starving braves arrived at Fort Qu’Appelle from Wood Mountain in a vain effort to obtain a reserve in Canada. [unnumbered page]

Qu’Appelle Fort was moved to the site on the flat prairie between Echo and Mission lakes by Peter Hourie, an Orkney half-breed, in 1864; and it was while Hourie was post master that Archbishop Tache, great grandnephew of the courageous La Verendrye, established a mission under Father Richot near the fort. In 1868 the mission was re-established four miles below the fort at what is now Lebret by Father Decorby. Faint traces of the Metis trail from Katepwe and Mission lake to the Hudson’s Bay fort can still be seen.

The story of the Swan River district, more especially of the Qu’Appelle post, between 1867 and 1874 has been told in detail by Isaac Cowie, whose “Company of Adventurers” is an unfailing (though not always acknowledged) source of information about Qu’Appelle and the country to the west—at that time the battle-ground of Crees and Saulteaux against the Blackfeet and their allies.

On the night of October 26th, 1867, Apprentice Clerk Cowie reached the Hudson’s Bay frontier post, then a stockaded enclosure of about one hundred and fifty feet square facing the bare northern slopes of the valley—slopes as bare today as in that far-off time when Metis and Indians set the hills on fire that they might have early pasturage for their ponies, or that the buffalo might come in spring to feed on luscious young grass. Archibald McDonald, the post master, was absent spearing fish, but the young Shetlander was kindly received by Mrs. McDonald, a daughter of John Inkster, of Seven Oaks. Cowie’s description of the post is so interesting that one could wish for space to quote it in full. “At the rear of the square,” he tells us, “… stood the master’s house… thickly thatched with beautiful yellow straw…This and the interpreter’s house were the only buildings which had glass windows … all the other windows in the establishment being of buffalo parchment. The west end of this building was used as an office and hall for the reception of Indians … the east end contained the mess room and the master’s apartments … behind was another building divided into a kitchen and a cook’s bedroom and into a nursery for Mr. McDonald’s children and their nurse… On the west end of the square was a long and connected row of dwelling houses … each with an open chimney of its own for cooking and heating… Mrs. McDonald owned the American cook stove imported from St. Paul, Minnesota, in the kitchen. Directly opposite the row of men’s houses was a row used as fur, trading and provision stores, with, at the south end, a room for the dairy, and at the north end a large one for dog, horse, and ox harness… To the right of the front gate stood the flagstaff … and in the middle of the square was the fur packing press.” Outside the stockade was a large kitchen garden, and a ten-acre field containing potatoes and barley; there was also a hay-yard, stables for horses and cattle, and a log ice-house with a deep storage cellar. About a hundred feet from the fort was the ford of the Qu’Appelle. The ford, today known as “Water Horse,” is a favourite swimming place for the children of the town.

The prairie surrounding the fort was criss-crossed with buffalo paths, and deeply rutted cart trails led to the numerous Swan River posts. Qu’Appelle, the most westerly permanent station, had flying posts at Wood Mountain, the Cypress Hills, and various temporary feeding grounds of the migratory buffalo. In 1869 Joseph McKay of Fort Ellice, built an outpost of Qu’Appelle at Last Mountain. Communication with Fort Garry, at “The Forks” where all routes met, was by way of Fort Ellice and the voyageurs’ route down the Assiniboine, or overland past old Brandon House, Portage la Prairie, Poplar Point, and across the White Horse Plains. The troublous days [unnumbered page] of the transfer of Hudson’s Bay Company territory to Canada and the Red River Rebellion were times of great anxiety at Fort Qu’Appelle. Excitement over the troubles at Red River reached a climax in the spring of 1870, after the fall of Fort Garry and the murder of Scott by Louis Riel. The Metis squatters round the lakes and the buffalo hunters of the plains were naturally more or less sympathetic with their relations at Red River, and Mr. McDonald sent messengers to Loud Voice, Poor Man, and other friendly Cree chiefs to come to the fort and discuss the situation. A strong palisade of up-ended logs was built outside the existing stockade, and bands of Indians under Loud Voice camped in a protecting circle around the fort all summer.

Three years later even the most loyal of the Company’s Indians were puzzled or antagonized when a party of surveyors under Dr. Robert Bell came to the valley. No treaty had yet been made with the Indians of “the Fertile Belt,” and it was a most unwise action on the part of the Canadian government to send members of the Geological Survey into the territory.

On September 15th, 1874, the “first treaty between the Indians of the Northwest Territories and Queen Victoria, represented by her commissioners,” was signed at Fort Qu’Appelle. Early in the month Lieutenant Governor Morris, the Indian commissioner the Hon. David Laird, and W. J. Christie, a former Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, arrived at Qu’Appelle, and were given quarters at the fort by W. J. McLean, officer in charge; their escort under Lieutenant-Colonel Osborne Smith camped outside the palisade on the edge of the lake. It is a well recognized fact that the confidence of the Indians in the officers of the Company was invaluable to the Canadian Government, but the Indians now refused to meet the commissioners anywhere on the Company’s reserve, as “there was something in the way.” After much delay, Osborne Smith reported their reason was that it had been surveyed without their having been consulted, and it was then arranged that the conference should be held at Kee pa hee can nik (The Flats), a short distance to the west. The Crees, under Loud Voice, were present the first day, but Cote and his Saulteaux from Fort Pelly would not attend. “We are not united, the Crees and the Saulteaux,” said Loud Voice… “I am trying to bring all together in one mind, and this is delaying me.” A garbled account of the transfer of Hudson’s Bay territory to Canada had also reached the Indians, who claimed that the £300,000 paid the Company should have been given to them: “When one Indian takes anything from another we call it stealing,” said a chief known as The Gambler. Even Indians who had known and trusted Archibald McDonald for years seemed troubled to see him with the commissioners. “This man that we are speaking about,” said one of the chiefs, “I do not hate him; as I loved him before I love him still, and I want that the way he loved me at the first he should love me the same… I do not want to drive the Company anywhere… What I said is… they are to remain at their house. Supposing you wanted to take them away, I would not let them go … we would die if they went away.” Poor children of nature! So wise, so perplexed; so doubting, so trustful. One cannot but pity them as they signed away the goodly heritage that had been their fathers’ from time immemorial!

With the placing of Indians on reserves, the passing of the buffalo, and the advent of railways and settlers into the country, the Old West passed away, and the Company adjusted its trading methods to the changing life of the territories.

The season of 1882 is remembered to this day by old-timers as the year of high water on the Assiniboine and Qu’Appelle. When the spring floods [unnumbered page] abated Chief Factor McDonald moved from Fort Ellice to Qu’Appelle, which became headquarters of Swan River district. “Stirring times in the valley that spring,” says a former member of the Northwest Mounted Police, one of the escort of the Marquess of Lorne during his historic trip through the West in 1881. “The Hon. Edgar Dewdney, Lieutenant Governor, was camped at Fort Qu’Appelle before he selected Regina to be the capital; also his great opponent, T. W. Jackson; Archie McDonald, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay; and others.”

Through the courtesy of Mr. Ernest Read, once a clerk of the Company, I am able to give a description of the post in those colourful days. Mr. Read, a mere lad at the time, was with Major Boulton and the party who in 1879 crossed Bird Trail creek and were the first settlers round Shellmouth near the old Fort Pelly trail.

“When I first saw the fort in 1883,” says Mr. Read, “the factor’s residence was on the east side; the large packing plant and fur house were in the centre at south. A two-storey frame building stood in the southwest corner, the lower floor of which was used as an office, the four rooms above, used as bedrooms for the staff, opened on a wide hall which served as our sitting-room and was heated by a huge box stove. We had some jovial times there, especially when a Scot named Stewart played his bagpipes. To the north of this building was the coach-house, with ice-house underneath. Outside the palisade were the stables, and near them the whip-saw pit. The new trading store, with its innovation of a deep front for displaying goods, was also outside the palisade, to the north.”

On the stroke of twelve on New Year’s Eve the staff met at the factor’s house to wish him a “Happy New Year.” The bagpipes skirled, and a Scot named Noble danced the sword dance with brooms crossed on the floor in lieu of swords. “Where the McDonald sits is the head of the table,” and as long as Archibald McDonald lived at Fort Qu’Appelle his house on the Hudson’s Bay reserve was the centre of the whole community.

Changing conditions arose with settlement of the valley, and the Company no longer enjoyed a monopoly of trade. The first opposition apparently came from the firm of Mowat Bros., who about 1880 built a store to the east of the barracks of the Northwest Mounted Police and the house of Colonel Macdonald, Indian agent. With the development of the village of Fort Qu’Appelle, the trading store on the reserve became unsuitable, and in 1897 Chief Factor McDonald built a modern brick sales shop to the southwest of the fort. The office building was moved to the rear of the new store, and served as staff quarters till 1912 or ’13, when, having become too discrepit, it was sold by F. A. Jenner, manager of the store, for $100. The trading store built outside the palisade in 1883 was used as a storehouse for Egg Lake and Touchwood till it was demolished about 1903. A few of the axe-hewn square posts of the old fort may be noticed today serving as supports for clothes lines. The greater part of the palisade rotted and fell down, and sometime in the ’90’s the pickets were cut into firewood for the fort by Simon Gower, one of the earliest homesteaders of Wide Awake.

At the time the Company’s business was moved to the village, Mr. McDonald built what was then considered a palatial mansion near the site of the old packing plant and fur house. Traces of his former house to the southeast of the entrance gate may yet be faintly discerned beneath the prairie wool which today covers much of the site of the old fort. The only building remaining today is a pathetic shell of the addition built by Archibald [unnumbered page] McDonald to the residence as a schoolroom for the children. This building was used as an office for General Middleton and staff during the second Riel Rebellion, and in later years as a cook-house.

The small addition to the house was saved when all else was demolished. Did the old Chief Factor remember the days when the building echoed the laughter of children? Or was the building saved because of its historic connection? Who knows or cares? Its days of usefulness are over, and soon a pile of rubbish will be all that remains to tell of historic Fort Qu’Appelle.

Archibald McDonald retired on May 31st, 1911, having served the Company since 1854.

The descendants of Indians who once thronged round the old fort live on reserves near the valley, and hardly one of the men who served the Company at the post is now alive to tell of those stirring days. But you will not need to strain your imagination to visualize the phantom figures which still seem to haunt the site of old Fort Qu’Appelle; and if you would feel the inner charm of the unexploited Calling Valley you should wrap yourself in the warm folds of a “four point” blanket and sleep beside the old Metis trail between the mission and the fort. “In the dark of the night when unco things betide” the vanished people of the valley once more come to their own. Camp-fires blaze, and painted teepees are pitched on the shore; and above the beating of drums and the chants of medicine men you will hear the spirit voice of an Indian girl calling to her lover, and the far-off echoes answering “Qu’Appelle? Qu’Appelle? Qu’Appelle?”—The Beaver.

Advice

Dreamer

Cling to your vague,

Broken dreams … Even a

Shattered dream is better than no

Dream at all.

—Saskatchewan Farmer.

[unnumbered page]

RADIO

(The sinister side of radio broadcasting is seen at its worst in international relations… In Europe the air is used to intensify national antagonisms, with counterblasts from Rome and Berlin and Moscow. News item.)

This wonder knows no walls … I turn a dial

And listen to a lively roundelay:

Or some song underlaid with sorrow, while

An organ throbs and yearning violins play.

I seek short wave lengths… Shall I hear again

Music of waves on grey Atlantic shore?

Blithe note of skylark in an English lane?

Or skirl of ’pipes across a Scottish moor?

Unshackled Spirit, scorning bounds of space

Within whose eager hands all sound is furled!

Swifter than tempest, free as thought, you race

On speeding sandals round a listening world—

A world in which land, sky, and sea have been

Man-doomed to Terror… To the ghastly strife

Of bombing plane, and tank, and submarine—

Will winged words too spread Chaos in Man’s life?

[illustration: By permission of the Hudson’s Bay Company.]

[unnumbered page]

Moose Jaw Wild Animal Park

[illustration]

The small animal and bird sanctuary known as the Moose Jaw Wild Animal Park lies in one of the most unspoilt and beautiful valleys of Southern Saskatchewan, at the very back door of the city of Moose Jaw—“the place where the White Man mended the cart with the jaw bone of the Moose.”

One would like to believe the dramatic legend of the origin of the name of the city, but I am informed by Mr. A. H. Gibbard, Librarian of the Public Library, there is no evidence that the story of a British sportsman fixing his broken-down Red River cart with the jaw of a moose is anything but fiction. The city was named from Moose Jaw Creek, so named by Indians who thought the junction of the creek and the Qu’Appelle River formed an angle resembling the jaw bone of a moose.

The Park owes its existence to the unselfish efforts of a number of public-spirited men, who in 1928 organized the Moose Jaw Wild Animal Park Society. The objects of this association were: “To establish an animal and bird sanctuary featuring as much as possible an orphanage for young wild animals rescued from forest fires … and to develop a more intense desire for the protection of the animal, bird, and tree life of our country.” All money collected is spent in wages, feed, and general development, and no member of the Park Society is ever paid for services rendered. The services of a well-known veterinary surgeon are donated at any time to all birds and animals requiring treatment.

Between five and six hundred acres of land was given to the Society by Mr. John R. Green. By Order-in-Council the Park area, and all land within a radius of three miles outside the bounds, was declared to be a game sanctuary. Far off on the horizon can be faintly descerned the shadowy purple lines of the Cactus, or Dirt Hills; in the middle distance tall grain elevators, flour mills, and the sixteen story Registered Seed Grain building tower over the city—buildings as truly typical of the West as the Gothic cathedrals are of France, or the sky-scrapers of the United States. Shadowy figures of followers of Sitting Bull, who fled to Canada after the Custer Massacre, eventually finding a refuge near Moose Jaw, still seem to stalk deer and antelope across the wind-swept upland, or lead their ponies to water at Wak-ku-took-a-pu, the little creek which runs and loops through the Park. The spot where Joseph Delorme, an old Metis hunter who recently died near Lebret, killed the last of the innumerable buffalo which once roamed the Regina-Moose Jaw plain, is also supposed to be within the precincts. Delorme was with Father Hugonard, who was returning to his Mission in the Qu’Appelle Valley from Wood Mountain and Willow Bunch. Just as the party crossed a ford of the creek, two buffalo were seen feeding on the bank. Delorme was mounted on a swift buffalo runner, and succeeded in killing both animals. [unnumbered page]

In the spring of 1929 the Park was provided with elk, deer, buffalo, antelope, bear, and other animals by courtesy of the Federal Government. J. A. M. Patrick, K.C., of Yorkton, sent gifts of English Fallow deer, settings of eggs of Canada geese, and other birds. During the formal opening, under patronage of Lieutenant Governor Newlands, a brilliant historical pageant depicting the coming of Sitting Bull to the trading post of Louis Legare; a stirring episode in the story of the North West Mounted Police; and a Cree-Sioux sham battle was staged. Another version of the last buffalo hunt was told by Red Dog, son of Star Blanket of File Hills, who said his father killed the last buffalo near the plain on which teepees of Indians taking part in the pageant were pitched.

The Moose Jaw Park is unique in specializing in the care of orphan wild animal babies. Many of these bottle-fed animals become so tame and curious as to almost be a nuisance. Yet the instinct of antagonism to man develops in many of them; moose especially have proved very treacherous, and a very fine pair known as Darby and Babe “went bad”; resented the presence of strangers on the trails. Darby punctured radiators, and smashed car windows with his huge horns, and Babe, wild with fear on account of her calf. Tony, attacked a man. Eventually the three animals had to be destroyed.

Visitors to the Park are urged to remain in their cars while on the trails as it is the unvarying policy of the executive to allow every animal all possible liberty. Virginia, Fallow, and Mule deer; buffalo; Persian sheep; elk; and antelope roam at will inside the eight foot, heavy wire fence surrounding the Park. “Do not get familiar with any wild animal,” warns the caretaker, Mr. Thomas Grice. Even as he spoke, however, he was making his rounds closely followed by Dot, a Mule deer from Midnight Lake, and Nick, a Virginia deer rescued from a forest fire at Nipawin. Dot is probably the best known and most friendly wild animal in Saskatchewan; Nick unfortunately became so unruly a short time ago that he had to be killed.

Tiny fawns whimpering for peanuts, of which every animal in the Park is abnormally fond, follow the visitors everywhere. Creatures whose habits make liberty inadvisable are kept in comfortable pens near the creek and in the picnic grounds. Here we will find more or less friendly coyotes; bear cubs; Minnesota and Quebec squirrels; racoons; and porcupines. The Park’s feathered denizens include Silver and Golden pheasants; Canada and Egyptian geese; wild duck; swans; Pea and Guinea fowl; beautiful Blue quail from Virginia. The Park is also the breeding and distributing point for hundreds of pheasants.

Snowshoes and Jack rabbits scury everywhere; even the pestiferous gopher honeycombs the ground unperturbed by the “Go for the Gopher” campaign of the Government. Any lover of nature will find mystic beauty in this sanctuary from the time that pasque flowers—the “frost flower” of the Sioux that we mis-name crocus—carpet all the uplands with a misty mauve coverlet, till the biting frosts of a Western winter nip the last bright red berries on the prairie rose bushes.

Deer and elk browsing in the bluffs eat the foliage of many of the trees; the animals have increased so rapidly that the Park is overstocked and the question of maintenance is a serious one. As a result of prolonged drought the question of an adequate supply of water has become serious, especially for the busy beavers. Nevertheless the Managing Director, Mr. Frank McRitchie and his Executive face the future with the characteristic optimism of the sons of this “next year” West. [unnumbered page]

[illustration]

THE STORY OF REGINA’S

FIRST TREE, AND OTHERS

The unpretentious wooden homes of the first men and women who had faith in the future of the little town of Regina in the early eighties had hardly replaced the tents of the pioneers than a longing for trees in their environment was felt.

It is written in the yellowing pages of the first history of Regina—a slim volume by J. W. Powers, published by the Leader Printing Company in 1887, “On the 7th of May, 1886, the lieutenant governor, the town council, and interested citizens made a big Arbour Day, and planted … a suitable variety of trees.” We find on referring to old files of The Leader that May 4th had originally been set as the date of this first Arbour Day; unfortunately, however, “it rained magnificently … and no trees planted! The weather was dirty in the extreme. Rain, snow, and resurrected blizzards striving for the supremacy.”

An earlier news item states that the council were purchasing “a thousand young trees from a Minnesota nursery for sale at cost to the citizens. It is to be hoped that many will avail themselves of the opportunity given to beautify the town by tasteful planting.” A later item tells of the arrival of the trees—“Councillor Martin will dispose of them at cost on Thursday and Friday.”

Reginans were also informed that “the Gore is being plowed up in preparation for planting.” This “Gore” so often referred to in early days was a triangular piece of ground, fronting the station on South Railway street, on which the first pioneers pegged their tents. The name is recalled in the Albert street Gore today.

Most of the old timers who took part in the historic first Arbour Day have passed on. To one of them, Robert Martin, who remembers planting a poplar on that occasion, comes the information—verified by W. H. Duncan—that the first tree in Regina was probably that planted by Rev. Mr. Urquhart, of Knox church, in the 19 block Scarth street, near where Aren’s drug store stands today.

Headquarters of the N.W.M.P. was moved from Fort Walsh to Regina, and in September, 1882, portable tin huts, in which the men froze in winter and baked in summer, were set up under direction of Commissioner Irvine on the bare, treeless homestead of George Moffat, about two miles west of the station. Shortly after the close of the Riel Rebellion, Irvine was succeeded [unnumbered page] by Col. Lawrence Herchmer. “When my father arrived in Regina in 1886,” says Mrs. Strang (daughter of Colonel Herchmer), “there were no trees of any kind at the barracks, no grass but prairie wool; no fence surrounded the shabby buildings, and visitors cut across the place where they wished. Many Regina people were highly indignant when father made paths and roads, and fenced off the barrack square.” Poplars were brought by police teams from the Qu’Appelle valley, and Manitoba maples imported from Winnipeg. Inspector Routledge assisted the Commissioner in the work of improving the surroundings of the barracks. Hundreds of shrubs and saplings were later obtained from Angus MacKay of the Indian Head Experimental Farm. Herchmer also planted from seed rows of maples reaching from the officers’ quarters to the bridge near old Government House—a long, low building brought in sections from British Columbia—and was so successful with his seedlings that he thinned them out and gave saplings to the Legislative Librarian, Henry Fisher, of Bayswater farm, whose buildings and farm, four miles northwest of Regina, were among the finest in all Assiniboia; also to his near neighbor, D. F. Jelly, member for the town in the Territorial Council; and several other farmers living near Regina. It is probable that a very fine poplar, outside the quarters occupied by the late Mr. Heffernan when inspector, was the last remaining Herchmer tree. This beautiful tree was nourished in infancy by water, carefully saved from the officers’ baths, and carried to it by men confined to barracks.

“A damned nuisance it was, too,” the old sergeant asked to verify this local tradition, added reflectively.

A number of trees were transplanted from the barracks about 1895 to the grounds of New Government House by the head gardener, George Watt. As both Manitoba maple and poplar are short-lived, it is improbable than any of these trees are alive today; however, some of the spruce brought from Banff by Governor Forget still beautify the grounds. A number of spruce were also brought from Banff by Malcolm King, whose “Tor Hill” farm is now part of the city’s 2,080 acre Boggy Creek park. Many of the trees round the picnic grounds were planted by Mr. King, who also planted hundreds of ash, willow, poplar, and elm as a shelter belt, or in the evenue leading to his grey stone house. Many saplings from the vicinity of Boggy Creek were sold to Regina treelovers in early days by Henry—“Hank”—Anticknap, who is still well known in Regina.

Judge Richardson was one of the first “men of the trees”; his tree-surrounded house on Victora avenue is today the home of Peter McAra. Hayter Reed, Indian Commissioner, was another; his home was the second house on Scarth street to the south of where the Hotel Saskatchewan stands today; also the Superintendent of Education, Mr. Goggan, who lived in the house next to the hotel. Many fine old trees still flourish in the back yard of the house on Rose and Twelfth, built long ago by J. K. R. Williams; but the tree planted about the same date by J. W. Smith, of Smith and Ferguson, round his house on the opposite corner have long since disappeared. A few of the trees Mr. Smith planted in the grounds of his next home on the corner of Victoria and Hamilton—now the offices of the Trust and Loan Company of Canada—have been more fortunate. Judge Scott; William [unnumbered page] Henderson, Public Works Commissioner; and D. Mowat of Mowat Bros., earliest rivals of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Qu’Appelle were also among those who helped to make Regina “the tree-crowned queen of the plains.”

Another pioneer name written in living green is that of James Grassick. More than 45 years ago he planted trees round his home at 1821 Rose street. He still recalls with affection a poplar sapling outside his place on Lorne street which grew to be 14 inches at the butt, 40 feet in height, and is today justly proud of the trees on his property on College avenue.

It is probable that the first mountain ash tree in Regina flourished in the garden of Mr. J. M. Young, brother-in-law of Hon. Walter Scott.

When Mr. Young built the red brick house on the corner of Thirteenth and McIntyre—today the palace of the Roman Catholic Archbishop—he moved this precious tree from his house on Rose street to his new home. Other noteworthy trees are an elm in Wascana park and a poplar in the City Hall grounds given years ago by Wilmot Haultain to Venzke, a former parks superintendent; also two spruce trees in Wascana park, long known as “the Haultain Twins.” A very fine willow, a cutting from a tree in the famous Spring-Rice estate near Pense, is in Mr. Haultain’s own garden.

Death has at last overtaken a one-time fine tree planted many years ago at the corner of Scarth and Thirteenth by D. P. McColl, Deputy Minister of Education. This old tree struggled bravely for years; apparently dead, it put out new growth each spring, but succumbed in the winter of 1931.

With the expansion of the town, and the gradual encroachment of business building on the original residential section, many trees which had succeeded in their early struggle for existence were in danger of destruction. Due to the efforts of Norman Mackenzie, barrister, many of these pioneer trees were transplanted, and flourish today in his beautiful grove on Albert street. One of the most interesting of these salvaged trees is an historic elm, transplanted from the grounds of the old Legislative Building on Dewdney avenue when the offices of the Indian Department were demolished. Perhaps the finest elm in Regina is the one moved by Mr. Mackenzie from the corner of Broad and Twelfth when the Crapper property became too valuable for residential purposes. The elm was moved in winter by sleighs and teams, with an eight foot ball of earth, weighing approximately a ton and a half, adhering to the roots. One of the largest branches had been ripped off, and the tree was in danger of becoming the victim of insets or disease. A photo was sent to a famous firm of tree surgeons, who ordered the mound cleaned by an acid. A further treatment of tar, and cement divided by sticks was next prescribed and complete recovery resulted. Two white ash were also rescued from the Crapper property, and a large elm, planted nearby by Mr. Henderson, was also salvaged when his old house was pulled down. [unnumbered page]

During the building of the Hotel Saskatchewan many valuable trees were in danger of destruction from excavation and tar smoke. Two prospective victims, a tree planted by Judge Scott and a crabapple planted by Dr. Seymour, flourish today in Mr. Mackenzie’s grove close to a tree originally planted in what is now the business section by Mr. Mowat. Among many friendly old trees which beautify the garden of W. H. Duncan on Cornwall and Thirteenth is the large Russian poplar rescued, after it had been dug up and thrown aside during excavation work for the Telephone Exchange building on Lorne and Twelfth shortly before the 1912 cyclone. “This tree was only a small sapling, hardly more than an inch in diameter at the time,” said Mr. Duncan, “but it was a nice slender little poplar, and appealed to me as a good tree; so I picked it up and carried it home.”

Two other interesting trees which must be mentioned are those planted by Premier Gardiner and Mayor McAra in commemoration of Confederation in 1927.

In the early nineties of the last century the town of Regina and the Canadian Pacific jointly shared the expense of keeping up a small park with picturesque windmill, flower beds and trees. An illustrated booklet issued by the board of trade in 1911 shows that park areas marked with shelter-belts of young trees had already been set aside, and a fountain built in Victoria park, but apparently trees had not yet been planted on the newly laid out boulevards. In pre-war boom days marvellous plans—hanging today in the office of the Parks Superintendent—for a beautiful modern city were made by the famous firm of Mawson and Sons. The initial carrying out of these plans in the grounds of the Legislative Buildings was entrusted to Malcolm Ross, who was later with the Canadian War Graves Commission in Belgium. The miracle of transformation was continued by George Watt, who retired in 1930, and was succeeded by J. E. Park, a graduate of Manitoba Agricultural College.

Only a brief reference can be made to the work of the Regina Parks Department under J. M. Craig. The work of this department includes not only the upkeep of parks, greenhouses, nurseries, cemeteries, boulevards, but also the planning and maintaining of golf courses, picnic grounds, bathing pools, playgrounds hockey and skating rinks, and so forth. Statistics show that in one year alone 9,235 trees were pruned, and 3,560 shrubs thinned in our 4,578,000 square feet of boulevard. Lack of funds and abnormal weather conditions have prevented the carrying out of Mr. Craig’s plans for additional parks, playgrounds and boulevards, yet much has been done towards making Regina the “City Beautiful” previsioned by the pioneers. The Leader-Post.

[illustration]

[unnumbered page]

Good Listening

The radio, swift and free as thought, defiant of all bounds of space, recently brought over the air the story of Gabriel and Evangeline, read with haunting beauty in the heart of the Acadian country. As the sensitive voice of the reader re-created the pathetic story, gone were the sombre drought stricken prairies, gone the restless prairie winds. I heard the roar of the Atlantic boom above the lovely harmonies of the Acadian orchestra; the salt tang of the sea enveloped me as, in imagination, I stood on the shore of the Basin of Minas.

… Slowly, slowly, as in a dream, the grey mist lifted and rolled seaward. Far-off Blomidon rose out of the shadows, and the little village of Grand Pre stood clear-cut in the midst of orchards and yellowing cornfields. Figure after figure came out of the past. Children of thrifty Acadian peasants played in the long, wide street while their mothers spun at open cottage doors. Gabriel and Evangeline lingered long in the kindly dusk while Rene Leblanc, Benedict and Basil smoked and possiped together.

The music became quicker, lighter. It was the joyous day of the lover’s betrothal feast. High above the orchestra vibrated the shrill sound of Michael’s fiddle. The old man played well known airs brought long since from France. Young and old danced to the swaying, lilting tunes till the peal of church bells sounded across the fields.

The background of exuberant music became low and dirge-like as with savage roil of drums, soldiers of the English king marched into the church. When the inhuman edict commanding the expulsion of the Acadians was read, it was as though the tragedy were developing before my eyes. I heard the solemn, authorative voice of Father Felician rebuking the tumultous outbreak of his people. By the fierce light of the blazing village I saw distracted wives torn from their husbands and terror-stricken children separated from their parents. In the grey dawn Evangeline stood alone where ocean and Gaspereau met, watching Gabriel’s ship drift slowly out of sight…. The plaintive music of the orchestra died away … only the disconsolate lapping of the ebbing

ATLANTIC NOCTURNE

DEDICATED TO THE CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION

The swish of waves wakening forgotten memories;

Low swell of organ; a muted violin’s wailing strings;

A voice telling of stormy seas, Love Pity, Death and Beauty—

Brought west to me on radio’s mystic wings.

Sunset’s rose flush; trees; fragrance of mayflowers;

The joy and beauty of the tears in things;

Old memories of coasting ships; white drift of sea-gulls—

All brought to me on radio’s mystic wings.

Too soon is music of voice, violin and organ ended—

But in my dreams tonight I’ll stand once more

In that Acadian land; haunted by long, low, plaintive

Requiem of waves breaking off a mist-swept shore.

—Regina Daily Star.

[unnumbered page]

tide over wet sands broke the silence.

Unquestionably we all hear the radio plus ourselves, and our imagination colours the programme to which we listen. As the orchestra played an elusive, ineffably sad melody I again fell under the spell of the reader’s voice, and was an exile in alien lands with the friendless, homeless Acadians. I followed Evangeline in her weary pilgrimage in search of Gabriel. The sorrow of those tragically separated lovers was my sorrow.

As the last chapter in this “Tale of Acadie” came over the air I saw Evangeline wandering from cold northern plains to southern savannahs. In missionaries’ tents or far-off camps of hunters or soldiers, seeking—but never finding—Gabriel. I saw her living as a Sister of Mercy among the children of Penn, consecrating her life to the service of the poor, sick and destitute, at last finding her dying lover in the almshouse of the pestilent swept city.

…. The plaintive melody of Ave Maria floated over the air. Pathos, longing, hear-tbreak; the very soul of the story were in its throbbing measures … “Maria, listen to a maiden’s prayer” … The invocation swelled to vibrant sounds of exaltation and triumph…. “All was ended now, the hope and the fear and the sorrow; Meekly she bowed her head, and murmured, ‘Father, I thank Thee’.”

The last word in the last stanza of the tragedy of Gabriel and Evangeline had been read in the land that once was theirs. Reluctantly I turned off the radio. Yet in the stillness music seemed to linger—music and a voice reading Evangeline.—Valley Echo.

Evening at Lebret

(“God give hills to climb—and strength for climbing.”)

I have climbed a winding trail worn hard by feet of those

whose eager faith finds Thee in the Shrine making the hill

whence the first missionary gazed at the Qu’Appelle Valley

at daybreak—seeing teepees of Red River buffalo hunters

camped near the lake

in the valley below.

The last afterglow of living gold and crimson fades—

Night’s creeping shadows veil the ramparts guarding

Mission Lake. Only the drumming of partridge wings

or weird call of loon to his mate shatters the stillness:

lamps gleam; wolf willow smoke curls up from the Metis’ cabins.

On this quiet, lonely hilltop I have walked with Beauty,

and in the deepening silence

God speaks to me. [unnumbered page]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.