[illustration]

[handwritten: PB Shelley]

[unnumbered page]

Riverside College Classics

———————

SELECTED POEMS OF

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES

BY

GEORGE HERBERT CLARKE, M.A.

Formerly Professor of English in the University of the South

[illustration]

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO SAN FRANCISCO

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

[unnumbered page]

COPYRIGHT 1907 BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Riverside Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Printed in the U.S.A.

[unnumbered page]

To my Father

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

PREFACE

No one can attempt to deal with Shelley in editorial fashion without being conscious at almost every step of the great value of Professor Dowden’s biography of the poet, and of much of the other material mentioned in the Bibliography. I have tried, however, in preparing the Introduction and Notes, to maintain that independence of judgment which should characterize all Shelleyans, and to produce a text suitable indeed for student use, and conforming to classroom requirements, yet based on other than formally pedagogic principles. Literature, it seems, is not getting itself taught in our higher schools as vitally as we would like, despite immense critical apparatus. Is it because we are too judicial? Is it because a poem, like a person, invites affection before it yields confidence?

G.H.C.

MACON, GEORGIA, December, 1906.

[blank page]

CONTENTS

ix | |

ix | |

liii | |

lxix | |

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

8 | |

11 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

18 | |

19 | |

19 | |

20 | |

31 | |

33 | |

34 | |

34 | |

36 | |

36 | |

40 | |

147 | |

147 | |

147 | |

148 |

[unnumbered page]

148 | |

150 | |

150 | |

151 | |

152 | |

153 | |

154 | |

156 | |

158 | |

161 | |

165 | |

175 | |

187 | |

188 | |

189 | |

190 | |

190 | |

191 | |

191 | |

192 | |

193 | |

193 | |

194 | |

195 | |

195 | |

195 | |

197 | |

218 | |

218 | |

218 | |

219 | |

220 | |

222 | |

225 | |

229 |

[page vii]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration: FIELD PLACE]

INTRODUCTION

THE LIFE OF SHELLEY

EVERY life is a symbol as well as a history, — a symbol, perhaps it were truer to say, because it is a history. The life of Shelley as a man, exceptional as it appears, is at one with the genius of Shelley as a poet, — it was impulsive; generously ardent; filled with the scorn of scorn, the love of love; eager and anxious to establish universal justice, freedom, and happiness; but pursuing too characteristically the dehumanized method of importing goodness into men rather than that of winning men into goodness. The course of his life moved from the tense yet dark mood of Paracelsus, exultant in denial and challenge, to the high affirmations of Aprile, —

“. . . the over-radiant star too mad

To drink the life-springs.”

Had he lived, it is hardly possible that he would have failed to become at last

“. . . a third

And better-tempered spirit, warned by both.”

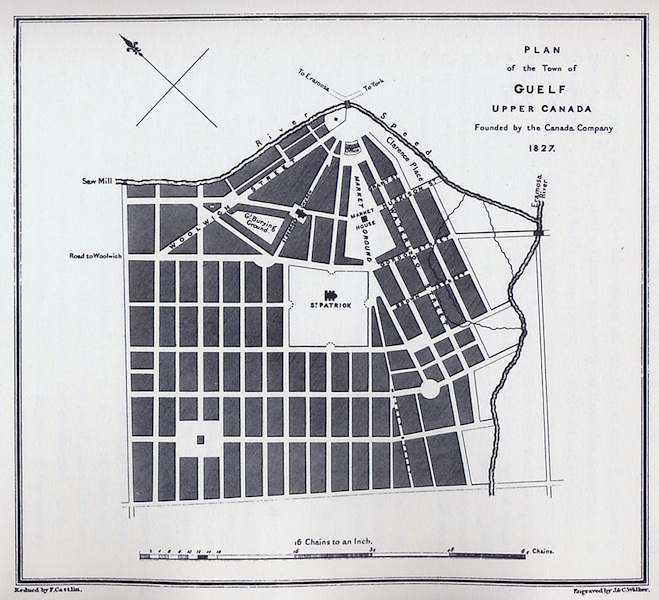

On the fourth day of August, 1792, their first child was born to Timothy and Elizabeth Shelley, at Field Place, near Horsham, Sussex. He was called Percy, because that was a favourite name in the Shelley family, ancient in Sussex; and Bysshe because that was the name of his paternal grandfather, a handsome, wealthy, and positive old gentleman, eventually made a baronet, who had been twice married, first to Miss Mary Catherine Michell, a Sussex heiress, who died after eight years of union, at the age of twenty-six; and again to Miss Elizabeth Jane Sidney, [unnumbered page] another heiress, this time of Kent, and a descendant of Sir Philip. It is interesting to note that, according to Medwin, the impetuous Sir Bysshe eloped in each instance, and also that he was usually on bad terms with his son Timothy, one of three children — the others being girls — born in the first family.

Timothy Shelley was a good-hearted rural Englishman of social importance and limited intelligence. He believed in the things that it was proper and dignified to believe in, and he expected equal conformity from his fellows, perhaps rather more of it from his inferiors. He had attended University College, Oxford, and had got himself duly elected Member of Parliament. He did his duty by the Church, the State, and the family, and was hardly less willing than his father to play Sir Oracle. In October, 1791, he married Miss Elizabeth Pilfold, of Effingham, Surrey, a somewhat unfeminine yet attractive and gracious woman. She became the mother of seven children, — two boys, Percy Bysshe and John, separated in age by fourteen years; and five girls, Elizabeth, Mary, two Hellens — one of whom died very early — and Margaret. Their adventurous and well-favoured brother was adored by the little maidens, who, during his stay at home, “followed my leader” in all sorts of thrilling excursions about house and garden. Quiet old Field Place spelled to these half-quaking explorers a land of mystery and portent, of golden enchantment, — a background for the most moving legends, told fearsomely by Bysshe to his awed companions. He was fond, too, like other imaginative children, of inventing remarkable but shadowy situations in which he had played a leading part, or again, he would detach himself from all, and go brooding about alone in the moonlight, save for a watchful servant in following discreetly at a distance.

After six secluded years of infancy and boyhood had passed, Bysshe became a pupil of the Rev. Mr. Edwards, of the village of Warnham, hard by. The four succeeding years [page x] he spent chiefly in studying Latin and developing his strength by somewhat irregular exercise. At ten he was entered at Sion House Academy, Isleworth, near Brentford. Here he found himself one of some sixty pupils, ruled by a Dr. Greenlaw, “a vigorous old Scotch divine,” writes Professor Dowden, “choleric and hard-headed, but not unkindly…. With spectacles pushed high above his dark and bushy eyebrows, the dominie would stimulate the laggard construers. Frequent dips into his mull of Scotch snuff helped him to sustain the wear and tear of the class-room.” Shelley’s slight, lithe, graceful figure was at once felt by the hoi polloi to present an irritatingly marked deviation from the norm, and they soon found that this was true also of his manner. His advent, accordingly, provoked roughness, persecution even, the more readily that the fagging system covered a multitude of petty tyrannies. Thomas Medwin, a cousin and biographer of Shelley, who was also a pupil at Sion House, describes him as “a strange and unsocial being.” Preoccupied as he was with his visions and imaginings, he gave only a constrained attention to either his schoolmates or his tasks, yet he advanced steadily in learning, and was transferred at the age of twelve to Eton. Meantime his taste for the eerie as steadily asserted itself: he read avidly the sixpenny dreadfuls, and was particularly charmed with the gothic romances of Mrs. Anne Radcliffe. He was also significantly interested in physical and chemical experiments.

Shelley must have passed from Sion House with scant regret, for he seems there to have been an all too willing Ishmael, save for a single friend; yet at Eton his situation was hardly improved. Though he found more friends of a sort, he found also more persecutors among both masters and pupils, and he was so often thrashed that he became dully apathetic to the mere bodily pain. Dr. Goodall, the head-master, a man of solid worth, was seconded in the Lower School by Dr. Keate, powerful with book and birch alike. Shelley entered the Fourth Form under Keate’s jurisdiction, [page xi] and resided first with a Mr. Hexton as his tutor and mentor, and thereafter with George Bethell, renowned in the history of Eton for his dulness and his good-nature. But neither Keate’s severity nor Bethell’s absurdity moved Shelley much. He still lived aloof for the most part, from the ordinary associations and requirements of school citizenship. So indifferent was he to the excitements of his five hundred fellows, and so fiercely resentful, not a physical hurt, but of injustice and the spirit of cruelty, that the came to be known as “Mad Shelley,” and was baited time after time for their amusement by a crew of thoughtless tormentors. When pushed to the limit of his patience, says one, his eyes would “flash like a tiger’s, his cheeks grow pale as death, his limbs quiver.” Such boys as he did attract, however, — though few but one Halliday appear to have had an instinctive understanding of him, — loved him for his unswerving honour, his kindness, and his generosity. With Halliday, Shelley took many a pleasant ramble in the fields and woods about Eton, pouring out his young soul in fits and starts of hope and enthusiasm. “He certainly was not happy at Eton,” wrote his friend in later years, “for his was a disposition that needed especial personal superintendence, to watch and cherish and direct all his noble aspirations, and the remarkable tenderness of his heart. He had great moral courage, and feared nothing but what was base and false and low.” From the same source we learn that his lessons “were child’s play to him.” He moved through the formal curriculum with ease, and chose to add to his school work outside the reading of such classical authors as Lucretius and Pliny, with Franklin, Condorcet, and his particularly Godwin — his future father-in-law — in his Political Justice. His fascinated interest in science, too, increased, and he ran not a few risks — both physical and magisterial — in his ardour for experiment. One likes to think of Shelley’s spiritual kinship with Shakespeare’s Ariel, creature of air and fire. Certainly, the young Etonian could have [page xii] found no better image of his own relentless adventurings than the balloons1 of fire he so often gave to the darkness, cleaving the gloom of night and steering their uncertain course into the company of moon and stars. Shelley’s science was a matter of lore and wonder rather than of knowledge and precision. This attitude, already characteristic, was encouraged by the boy’s contact with Dr. Lind, a retired physician living close at hand in Windsor, whose memory Shelley always regarded with a lively gratitude, and who is immortalized in The Revolt of Islam as the friendly hermit, and in Prince Athanase as Zonoras, —

“An old, old man, with hair of silver white,

And lips where heavenly smiles would hang and blend

With his wise words, and eyes whose arrowy light

Shone like the reflex of a thousand minds.”

Professor Dowden, in his admirably full and discriminating biography, speaks of two “shining moments” in Shelley’s youth, which were to the boy as moments of revolution. His experiences at Sion House led him to take careful thought concerning individual and popular unhappiness, its causes and conditions, and finally to vow in youthful yet serious fashion that he would never oppress another nor himself submit to tyranny. In the dedication of The Revolt of Islam — originally Loan of Cyntha — to Mary Shelley he writes: —

“I do remember well the hour which burst

My spirit’s sleep. A fresh May-dawn it was,

When I walked forth upon the glittering grass,

And wept, I knew not why: until there rose

From the near schoolroom voices that, alas!

Were but one echo from a world of woes —

The harsh and grating strife of tyrants and of foes.

“And then I clasped my hands and looked around;

But none was near to mock my streaming eyes

1 Shelley was fond, too, of sailing miniature paper boats. Cf. Rosalind and Helen, 11. 181-187.

[page xiii]

Which poured their warm drops on the sunny ground.

So, without shame, I spake: ‘I will be wise,

And just and free, and mild, if in me lies

Such power, for I grow weary to behold

The selfish and the strong will tyrannize

Without reproach or check.’ I then controlled

My tears, my heart grew calm, and I was meek and bold.”

If in the first moment Shelley felt his conscience quickened and dedicated to the cause of liberty, so in the second his imagination sought deliverance from the bondage of the merely horrible and sinister, and began instead to seek pure beauty and pursue it. This moment, too, he has fixed for us in his Hymn to Intellectual Beauty: —

“While yet a boy I sought for ghosts, and sped

Through many a listening chamber, cave, and ruin,

And starlight wood, with fearful steps pursuing

Hopes of high talk with the departed dead.

I called on poisonous names with which our youth is fed.

I was not heard, I saw them not;

When, musing deeply on the lot

Of life, at that sweet time when winds are wooing

All vital things that wake to bring

News of birds and blossoming,

Sudden thy shadow fell on me: —

I shrieked and clasped my hands in ecstasy!

“I vowed that I would dedicate my powers

To thee and thine; have I not kept the vow?

. . . . . . . . . . .

They know that never joy illumed my brow

Unlinked with hope that thou wouldst free

This world from its dark slavery,

That thou, O awful LOVELINESS,

Wouldst give whate’er these words cannot express.”

These passages were conceived by a saner mind and written with a steadier hand than were the rather prolific effusions of Shelley’s earlier youth, productions which began first at Eton to court pen and paper. Several fragmentary poems belong to this time, as also the extravagant romance, Zastrozzi, written probably in collaboration with [page xiv] Harriet Grove. Shelley’s cousin and sweetheart. Indeed, collaboration was something of a habit with the boy, not, it would seem, through any lack of confidence in his own creative powers, — for young Shelley was much less disturbed than his riper self by doubts concerning his own works, — but rather as the co-operative impulse of a spirit willing to share its enthusiasms with kindred spirits. He formed literary partnerships with his sisters Elizabeth and Hellen, with Medwin, and possibly also with Edward Graham, a friend of 1810-1811. Graham may have been associated with the “Victor and Cazire” project, the appearance of a volume of poems that were wild and whirling indeed, but of which all the copies — save one, since reprinted — were apparently destroyed or suppressed. More probably, however, Elizabeth was the “Cazire” of the partnership. Medwin helped to shape the beginnings of a romantic Nightmare, and a poem about that persevering pilgrim, the Wandering Jew. Apart from their biographical interest hardly one of these works is worth naming.

Complacent Mr. Timothy Shelley had no manner of doubt that his son — peculiar in some respects though he seemed — would do about as well as at Oxford as he himself had done, and the two travelled up thither amicably to arrange for Bysshe’s entrance upon residence in University College at the beginning of the Michaelmas term of 1810. Mr. Timothy was graciously paternal, and even went so far as to introduce his son to a local printer named Slatter, with the suggestion that this man should indulge the youth “in his printing freaks.” Rooms were secured, money matters adjusted, advice freely given, and the Polonius of Field Place departed in high good-humour with himself and all the world. He would have been interested, perhaps, to know what was passing in Bysshe’s mind as he looked about him at Oxford, deciding what he liked and what he did not like. He liked seclusion, the libraries, the natural beauty of the place; he did not like its sleepiness, its conservatism, [page xv] its orderly academic routine. One is strikingly reminded of Bacon’s indictment of the Cambridge of his day: “In the universities, all things are found opposite to the advancement of the sciences; for the readings and exercises are here so managed that it cannot easily come into any one’s mind to think of things out of the common road….For the studies of men in such places are confined, and pinned down to the writings of certain authors: from which, if any man happens to differ, he is presently represented as a disturber and innovator.” Shelley’s mind — alert, original, though always in certain respects untrained — thought of many things out of the common road. His prime Oxford “innovation,” it is true, was not carefully conceived or tactfully presented. It was a piece of folly for which he paid dear, but it was not dishonourable, nor was it even “dangerous” in any vital sense. Soon after his arrival he made the acquaintance casually of a fellow-freshman, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, a well-born and worldly-wise young man of considerable cultivation, easy opinions, and a half-cynical, half-amused, interest in the people he met and in the problems he heard them discuss and on occasion discussed with them. Ten years later Shelley thus described him, in his Letter to Maria Gisborne: —

“I cannot express

His virtues, though I know that they are great,

Because he locks, then barricades, the gate

Within which they inhabit; — of his wit

And wisdom, you’ll cry out when you are bit.

He is a pearl within an oyster shell,

One of the richest of the deep.”

Hogg was strongly attracted by Shelley’s looks, sincerity, and enthusiasms. The two met night after night in each other’s rooms, and debated questions of literature, science, and history, on Shelley’s side with fervour, on Hogg’s with growing interest in this rara avis, an interest almost wonder. Hogg deeply respected Shelley’s power of imagination and purity of [page xvi] character, though he allowed himself to be entertained by his new friend’s extravagances of manner and statement. He has left us in his Life of Shelley a detailed and picturesque account of the poet as he knew him during their six months’ comradeship at college. He describes Shelley’s figure as “slight and fragile, and yet his bones and joints were large and strong. He was tall, but he stooped so much that he seemed of a low stature. His clothes were expensive, and made according to the most approved mode of the day; but they were tumbled, rumpled, and unbrushed. His gestures were abrupt, and sometimes violent, occasionally even awkward, yet more frequently gentle and graceful….His features, his whole face and particularly his head, were, in fact, unusually small; yet the last appeared of a remarkable bulk, for his hair was long and bushy, and in fits of absence and in the agonies (if I may use the word) of anxious thought, he often rubbed it fiercely with his hands, or passed his fingers quickly through his locks unconsciously, so that it was singularly wild and rough.1 . . . His features were not symmetrical (the mouth, perhaps, excepted), yet was the effect of the whole extremely powerful. They breathed an animation, a fire, an enthusiasm, a vivid and preternatural intelligence, that I never met with in any other countenance. Nor was the moral expression less beautiful than the intellectual; for there was a softness, a delicacy, a gentleness, and especially (though this will surprise many) that air of profound religious veneration that characterizes the best works, and chiefly the frescoes (and into these they infused their whole souls) of the great masters of Florence and of Rome.” Only his voice did Hogg find displeasing, which seemed to him at first “intolerably shrill, harsh and discordant.” Other friends and contemporaries speak also of this defect, but generally agree that it was observable only in moments of high excitement, and that Shelley’s normal tones were winsome enough.

The two friends not only read and talked together, but

1 Cf. “his scattered hair.” — Alastor, 1.248

[page xvii]

Hogg would incredulously watch Shelley performing his always miraculous chemical experiments, or they would tramp about the countryside — Shelley seemed rather to float — and meet with adventures more or less exciting. Shelley cared little for the studies imposed upon him, and pursued his intellectual investigations with a free mind and in entirely free manner within the privacy of his chambers, reading Plutarch, Plato, Hume, Locke, the Greek tragedies, Shakespeare, and Landor. He continued also to write, publishing at his own expense another Etonian romance, — and failure, — St. Irvyne, or The Rosicrusian; some political verse; and a volume of miscellaneous poetry containing burlesques that pleased undergraduate taste, printed together with some more serious work produced spasmodically. That Shelley could have been willing at this date to publish, though anonymously, his crude and overstrained tale, and to push its fortunes with enthusiasm, attests perhaps better than any other single fact the condition of his critical judgment during the Oxford days. The poet in him must surely have been protestant the while! “I am aware,” he wrote to Stockdale the publisher, after reaction began to be felt, “of the imprudence of publishing a book so ill-digested as St. Irvyne.” Stockdale, for his part, from whatever motive, stirred up trouble for Shelley at home by calling his father’s attention to the unsoundness of his views and attributing this to his continued association with Hogg. Parental — chiefly paternal — intervention followed, only to confirm Shelley in what candour must designate as the heroic of the misunderstood. He vowed excitedly to defend his principles to the last, and to remain loyal to his friend at all hazards. His elders did not treat him with the wisdom born of humour and sympathy; they did not know the way to his heart, and had they known it they would have found that heart at the moment out of tune and harsh. Harriet Grove’s affection was not proof against her alarm at Shelley’s reputed heresies and his own exaggerated declarations of belief and unbelief. [page xviii] She both loved and dreaded the strange youth; prudence prevailed, and in 1811 she married “a clod of earth,” as Shelley described him, a Mr. Helyar. The boy felt the blow keenly, philosophized at length concerning it, and in a letter to Hogg written from Field Place during the Christmas vacation anathematized Intolerance, the cause of all his woes, He now planned that Hogg, should marry Elizabeth, his elder sister, who was affectionately consoling him at home. At least his friend should be happy.

Most, perhaps all, of this coil had been avoided if the prime actor therein had been less intense in behaviour, and his friends more willing to rely on his personal goodness and root docility. It is far from the mark to allow that Shelley was at any time a deliberate atheist. No man, it is safe to say, has felt more directly and continually than did he the existence of a beneficent Spirit. As an undergraduate, it is true, he was affected in his thought by the dogmas of materialism, but at no time ceased to postulate the being of an ultimate Intelligence and Love. It would be difficult to find in pure literature a more eager hunger and thirst for holiness and the Source of holiness than appears in Shelley’s Adonais, The Cenci, Hellas, The Revolt of Islam, and Prometheus Unbound, not to speak of his just and reverent Essay on Christianity. With what he conceived to be the inherent taint of ecclesiasticism, indeed, he was constantly at war, like Chaucer, Milton, Ruskin, Carlyle, and Browning, in their diverse ways; though, unlike them, he attacked not merely the taint, but also, and with fierce energy, the entire churchly system. In this regard he betrayed unusual zest, as witness the implications of character in cardinal and pope in The Cenci, and the vivid pictures of the Prometheus, when compared with Chaucer’s good-humoured revelations in The Canterbury Tales, and Browning’s half-friendly condemnations of Blougram and his kind. Shelley unfortunately tended to identify always priesthood with tradition, the church with uncompromising [page xix] and persecuting conservatism. There is in his work no “povre Persoun of a toun,” no Innocent XII. He did not habitually see both sides, though in one of his more pensive moods he actually expressed a desire to become himself a minister. “Of the moral doctrines of Christianity I am a more decided disciple than many of its more ostentatious professors. And consider for a moment how much good a good clergyman may do.”1 But for a moment only was this considered. Shelley wished characteristically to dispense for good and all with the “law” idea, and to bring the sorely suffering world out into the light of knowledge, virtue, love, and freedom. He knew what prayer meant; he was deeply moved by awe and wonder in contemplation of the eternal mysteries. In brief, he was not the enemy of religion that he thought he was; he everywhere proclaimed the efficacy of Love in healing and redeeming humanity. In later years Dante and Petrarch, in some respects, modified his aversion to historical Christianity, for through their works he came to feel keenly its spiritual beauty and power. His own religious instinct and attitude as a youth are suggested for us in two stanzas of Wordsworths’s Ode to Duty: —

“There are who ask not if thine eye

Be on them; who, in love and truth

Where no misgiving is, rely

Upon the genial sense of youth:

Glad hearts! without reproach or blot,

Who do thy work, and know it not:

Oh! if through confidence misplaced

They fail, thy saving arms, dread Power! around them cast.

“Serene will be our days and bright

And happy will our nature be

When love is an unerring light,

And joy its own security.

And they blissful course may hold

Ev’n now, who, not unwisely bold,

1 From a conversation with Thomas Love Peacock, reported by him.

[page xx]

Live in the spirit of this creed;

Yet seek thy firm support, according to their need.”

The freshman of University College, however, with a passion for negations and for reform, was in no mood to consider his ways and be wise. He was but too “unwisely bold.” Almost immediately after his return to Oxford, he arranged, with Hogg’s connivance, if not collaboration, for the anonymous publication of little pamphlet entitled The Necessity of Atheism. His motive in doing so was a mixed one, — partly sincere; partly, no doubt, dramatic. The argument, what there is of it, follows the beaten materialistic track, assuming throughout that sense-knowledge is all of knowledge, but the author seems to lament the “deficiency of proof” and to court sympathy and help. Not a few sedate dignitaries, to whom Shelley addressed copies of the pamphlet, with a specific request from “Jeremiah Stukeley” for counsel concerning it, fell into the trap and furnished their correspondent with much-desired controversial openings. Shelley had sent a copy to the Vice-Chancellor and to each of the Masters, and by his own Master he was interrogated and condemned. Upon “contumaciously refusing” either to acknowledge or to disavow the authorship of the paper, he was summarily expelled. From the stern conclave of Master and Fellows he rushed nervously to Hogg with the fateful news; Hogg instantly entered the breach, and drew upon himself a like examination, with a like result. If the judges hoped that submission might finally be made, they were disappointed, and the sentence had to stand. The anger of the authorities rapidly cooled, but that of Shelley and Hogg flamed and mounted. The next day, March 26, 1811, they left Oxford together for London. She who might have become more and more truly Shelley’s Alma Mater had behaved in a moment of natural impatience as his Dura Noverca.

After visiting friends and skirmishing about London in [page xxi] search of comfortable lodgings, which by some strange irony they found at length in Oxford Road, on Poland Street, — the “Poland,” at least, reminded Shelley of “Thaddeus of Warsaw and of freedom,” — the two young men settled down to their habitual comradeship, until interrupted by the appearance of Shelley’s father, freshly fortified by Paley’s Natural Theology. He had already written to Bysshe, requiring implicit future obedience and a rupture with Hogg as the price of his continued goodwill. He had also adjured Mr. Hogg, Sr., to assist in separating the two. Bysshe smiled mournfully at his father’s blustering theological expostulations, but flared up at the conditions named as ensuring a welcome home. These he deliberately rejected, feeling that to forego liberty of action was to forego all, and that his truth of character, as well as his personal affection for Hogg, demanded the persistence of the friendship. Hogg, however , soon withdrew or was withdrawn to York to read law, and Shelley, who planned to follow him later, and who was at this time half willing to study medicine, found himself for this the first moment in his life concerned about the means to live. His father had cut off all aid, and Bysshe was constrained to accept secret gifts from his devoted sisters, and the more substantial assistance of his uncle, Captain Pilfold, who had a strong liking for the youth. The girls sent their contributions though sixteen-year-old Harriet Westbrook, a close friend in their school life at Mrs. Fenning’s, Clapham. Harriet, being a resident of London, and possessing, therefore, the requisite freedom, bore many messages — both real and personal — between sisters and brother. Her father, John Westbrook, was a former tavern-keeper of some property, and her sister Eliza, a “Dark Lady,” her senior by many years, exercised an almost maternal control of her. Harriet was a winsome lass, exquisitely neat and pretty, and of a cheerfully sentimental disposition. She shared the indignation of the Shelley girls at the ill-treatment accorded their brother, and she found that brother a [page xxii] particularly attractive and interesting young man. Though at first much distressed at the perversity of his views, she rapidly came under the charm of his earnest manner and luminous deep-blue eyes, so rapidly that before many weeks had passed her heart began to whisper a secret. Shelley, for his part, knew nothing, or at least thought nothing, of such a possibility, but took a hearty pleasure in the comings of Harriet and in their conversations. He visited her at home and at school, and wrote frequently concerning matters they discussed. Harriet’s health thereafter began to fail, and Shelley, attributing this to some minor school “persecutions” and the major offence of her father in insisting on her continued stay at school, again broke a lance with Intolerance. Shortly afterward, Harriet’s preceptress discovered one of Shelley’s letters in her possession, warned both her and his families, and even, it is said, suspended Harriet.

Meanwhile, though the intervention of Captain Pilfold and the Duke of Norfolk, Mr. Timothy Shelley’s political chief, that gentleman became, in a measure, reconciled to his son, endowed him unconditionally with ₤200 a year, and consented to receive him at Field Place. Once again at home, Shelley found constraint even in his mother and Elizabeth, dearly as they loved him. Elizabeth scorned his desire that she should accept Hogg. To the latter Shelley wrote: “I am a perfect hermit, not a being to speak with! I sometimes exchange a word with my mother on the subject of the weather, upon which she is irresistibly eloquent; otherwise, all is deep silence! I wander about this place, walking all over the grounds, with no particular object in view.” He wrote not only to Hogg, but also to the Westbrook sisters and to Miss Elizabeth Hitchener, a keen and nervously intellectual schoolmistress whom he had met at Captain Pilfold’s house in Cuckfield.

The home of his cousin, Thomas Grove, near Rhayader, Wales, shortly succeeded York as Shelley’s objective point. [page xxiii] In the midst of this beautiful country he dwelt a while, unhappy and distraught, writing copious letters and marking time in a dubious mood. Though the Westbrook ladies were also in Wales at this time, he did not see them, but, upon their return to London, was shocked to receive from Harriet several letters expressing mingled misery and entreaty, — misery at the thought of returning to a school where what she felt to be unbearable persecution awaited her, and entreaty for sympathy and help. Shelley responded warmly, counselling resistance, and even addressed a letter of advice and remonstrate to Mr. Westbrook, a letter which he declined to heed. Harriet wrote once again, appealing to Shelley to save her from fear and tyranny, and the highhearted youth — he was now only nineteen — posted at once to London, saw Harriet, was amazed at her altered appearance, and enlightened only when she falteringly told her love. Shelley doubtless felt as Jules in Browning’s Pippa Passes: —

“If whoever loves

Must be, in some sort, god or worshipper,

The blessing or the blest one, queen or page,

Why should we always choose the page’s part?

Here is a woman with utter need of me, —

I find myself queen here, it seems!”

In a letter to Hogg he speaks of his course as resembling rather “exerted action” than “inspired passion.” Late in August Bysshe and Harriet fled — a long, slow flight it was — by coach to Edinburgh, where they were married August 28, 1811.

Both husband and wife — despite financial troubles, for Shelley’s father, deeply incensed against his son, again withdrew his aid — spent a bright honeymoon of five weeks in Edinburgh. Hogg shortly arrived from York, and was domiciled with his friends. Edinburgh in itself did not then attract Shelley, but the three shared one another’s enthusiasms in matters literary, social, and political, even if Harriet [page xxiv] somewhat surprised Shelley and Hogg by persistently reading aloud from sententiously moral books. She was not a cultured woman, but only a bright, eager, undiscriminating schoolgirl, very willing to accept her liege’s opinions, and yet trifle positive in presenting hers. Shelley’s increasing anxiety concerning income was allayed a little by the goodness of Captain Pilfold, who proved himself now, as before, a substantially corporeal guardian angel. From Edinburgh the travellers moved on to York, Bysshe shortly resolving to seek a personal interview with his father. He made a hasty trip into Sussex, as the guest of his uncle, only to be met with Mr. Shelley’s curt refusal of help. A delightful conversation with Miss Hitchener, whose fine mental and spiritual qualities he characteristically overrated, was his only gain. Passing through London, he returned to York to find Eliza Westbrook had come north and had assumed charge of his establishment. Though Shelley was aware of this plan, and had forwarded it, he seems to have been somewhat disconcerted. A strict domestic programme was inaugurated, and was meekly accepted by Harriet, who was a clay in Eliza’s hands; and by Shelley, who could only look on and wonder; and by Hogg, who was not considered at all. Harriet, indeed, was feeling the need of protection form Hogg’s unworthy interest, an interest which shortly cost him the comradeship, though not the continued friendship, of a grieved and troubled Shelley. From York the little company, still numbering three, but with Eliza in the place of Hogg, proceeded to Keswick and settled in Chestnut Cottage, near Derwentwater and Bassenthwaite. Here they stayed for several months, Shelley occupying himself with the beautiful nature aspects and with divers literary enterprises, including a collection of his shorter poems, another of essays, and a political novel, Hubert Cauvin, of which nothing is now known. With the people of Keswick Shelley had little to do, though he met and admired friendly William Calvert, and through him became [page xxv] acquainted with Robert Southey. The older poet — different in temper and theory as the two were — showed the younger much practical kindness, but though Shelley met his early advances with some eagerness, he soon afterward wrote to Miss Hitchener: “I do not think so highly of Southey as I did….I do not mean that he is or can be the great character which once I linked him to; his mind is terribly narrow compared to it….It rends my heart when I think what he might have been!”

The Duke of Norfolk was again to act as mediator between the Shelleys — father and son — in response to a manly letter from Bysshe requesting his service. The matter was not at once adjusted, but negotiations were opened, and before long the young couple and Miss Westbrook were invited to Greystoke, the Duke’s neighbouring seat. Shortly afterward it was intimated to Shelley an income of ₤2000 annually might become his if he would consent to entail the estate in favour of a possible son or of his brother John. Shelley, who strongly opposed the law of primogeniture and believed that he had no moral right to accept this tentative suggestion, declined it with indignation and without parley. Should he himself inherit the estate — which he thought unlikely, as he anticipated an early death — he purposed to share it with his friends. Before this discussion arose, however, Shelley, by the advice of the Duke, had sent his father a letter so just and kind that a favourable response was induced, and by January, 1812, an annuity of ₤200 was again settled upon him. This, with a similar sum granted by Mr. Westbrook for Harriet’s subsistence, saved the young people from what had become a really acute though temporary poverty.

It will be recalled that Shelley, while at Eton, was much interested in Godwin’s revolutionary book, Political Justice. His interest had so grown that when he now heard casually of Godwin’s continued physical existence — he had supposed him dead — he eagerly penned a letter overflowing [page xxvi] with respect and admiration, for Shelley the proselyte was no less ardent than Shelley the proselytizer. Godwin found his communication sufficiently interesting to warrant a reply inviting particulars of the writer’s history. These Shelley immediately supplied, and a steady correspondence followed, — Godwin’s letters being friendly and hortative, Shelley’s tractable but animated. In one of these Shelley announced his purpose of going into Ireland, there to aid in Catholic Emancipation, asking and receiving much good advice from Godwin concerning this course. Miss Hitchener was invited to join the party, but declined, and Shelley, with his wife and sister-in-law, left Keswick February 2, 1812, arriving in Dublin, after tiresome delays, ten days later.

In parlous Ireland Shelley found work at first to his liking. Caring little for Catholic Emancipation in itself, — he owned “no cause,” he wrote to Godwin, “but virtue, no party but the world,” — he nevertheless threw himself eagerly into the service of the politically oppressed. He issued an Address to the Irish People that created some stir, and until dissuaded by Godwin, sought to form a peaceably revolutionary “Association of Philanthropists.” Harriet and he must have greatly enjoyed their methods of distributing the pamphlets he wrote, sometimes throwing them from the window to “likely” persons. On the 28th Shelley spoke with some acceptance at a public meeting, and thereafter met, though with scant satisfaction, several of the leading Irish patriots. He encountered praise, blame, and suspicion, but made himself a manful missionary until personal reaction set in, a reaction due partly to the failure of his efforts to modify the situation in any practical way, and partly to Godwin’s rather chilling criticisms. At length, on April 4, he left Ireland for Holyhead, and after several wandering days, pitched tent at Nantgwillt, North Wales. Here he penned one or two literary studies, and met and liked Thomas Love Peacock, a liberal, cultured, pleasing man and writer, thenceforth Shelley’s friend. But again stakes were up, and the [page xxvii] pilgrims away, first to the Groves’ home, near by, and then to Chepstow, and the Lynmouth, Devon. Amid the entrancing coast scenery they stayed two months, and here they welcomed the advent of Miss Hitchener, whose extraordinary charms, however, slowly lapsed into commonplace in Shelley’s as in Harriet’s thinking. From “soul of my soul” she became, through several transitions, “Brown Demon.” Much reading and writing went on in Lynmouth, and at this time Shelley was busily at work upon his Queen Mab. Here, too, he wrote his birthday sonnet and his blank verse apostrophe to Harriet, and penned his energetic Letter to Lord Ellenborough concerning the prosecution of one Eaton, a poor bookseller, for publishing part of Paine’s Age of Reason. The Devon coast saw Shelley often engaged in the boyishly serious business of scattering his revolutionary writings to the world at large through the media of bottles, sea-boxes, and fire-balloons. The arrest of his manservant, however, while distributing copies of the Shelleyan Declaration of Rights, decided the swift mind. When Godwin arrived in Lynmouth, September 18, he found his discipline flown.

During the next year Shelley travelled variously in all parts of the United Kingdom. He settled first at Tan-yr-allt, near Tremadoc, Carnarvonshire, and turned from the reform of humanity to that of nature, earnestly aiding W. Alexander Madocks, M.P., in his attempt to reclaim several thousand acres of land from the sea. While visiting London in order to raise a subscription for this project, he seized the opportunity to visit the home of Godwin, where he met, besides the old philosopher, — who looked, Harriet thought, like Socrates, — the second Mrs. Godwin also, her young son William, and Fanny (Imlay) Godwin, born to Mary Wollstonecraft before she became Godwin’s first wife. Clara Jane Clairmont, daughter of Mrs. Goldwin and her first husband, and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, daughter of Godwin and his first wife — a sufficiently complicated [page xxviii] family, this! — were absent during most of the time of Shelley’s stay in London, and, though both were soon to become closely concerned with the life of the poet, he has left on record no minute of his impressions, if he then saw them. While in London Shelley made other friends also, and sought out Hogg, permitting such renewal as was possible of their old association. Miss Hitchener, her pedestal being lost, took her final leave of Shelley hospitality. “We were entirely deceived in her character as to republicanism,” wrote Harriet to an Irish friend, Mrs. Catherine Nugent, “and in short everything else which she pretended to be.” By November 15 Tremadoc was again in sight, and months of happy domesticity followed, Shelley reading much, continuing Queen Mab, relieving the distresses of the poor about him, and consuming his soul in indignation at the imprisonment of Leigh Hunt for a libel upon the Prince Regent. Late in February, 1813, a burglarious attack was perhaps made upon the poet’s home, and his life seems to have been in some danger. At all events, the incident1 was nervously magnified by Shelley into “atrocious assassination,” and, convinced that some sinister villain was on his track, he left again for Dublin. Thence the young family journeyed to the beautiful Killarney Lakes, and by April were again in London.

Queen Mab, a long, uneven, unrhymed poem, lyric and heroic, far more representative of the boy Shelley than of the man, was completed in spring, and was printed for restricted distribution. In 1821, its author described it as “a poem….written by me at the age of eighteen — I dare say, in a sufficiently intemperate spirit….I doubt not but that it is perfectly worthless in point of literary composition;

1 In an interesting article in The Century Magazine for October, 1905, A Strange Adventure of Shelley’s, Margaret L. Croft presents evidence that one Robin Pant Evan, a rough Welsh sheep-farmer, deliberately broke into Tan-yr-allt in order to frighten away Shelley, his ire having been aroused at the poet’s humane practice of killing his neighbours’ hopelessly diseased sheep.

[page xxix]

and that, in all that concerns moral and political speculation, as well as in the subtler discriminations of metaphysical and religious doctrine, it is still more crude and immature.” During the same year he wrote to Horace Smith: “If you happen to have brought a copy of Clarke’s edition of Queen Mab for me, I should like very well to see it. — I really hardly know what this poem is about. I am afraid it is rather rough.” The Ianthe in the poem gave her name to Shelley and Harriet’s first child, Ianthe Elizabeth, born the following June. Shelley’s September sonnet, To Ianthe, expresses the growing love he bestowed upon the infant. After her coming a removal was made to Bracknell, in Berkshire, at the suggestion of Mrs. Boinville, a cultured and high-principled woman, and her daughter, Cornelia Turner, whom Shelley had met in London. From Bracknell they went into the Lake country, and thence to Edinburgh again, with Peacock, but by December were back in London, securing a temporary home in Windsor, near Bracknell. Shelley was now feeling keenly the need of additional income, and had lately paid a clandestine visit home. He wrote once again to his father for consideration, urgently, but in vain. Such money as was imperatively necessary to him, therefore, he raised on post-obit bonds.

The biographers of Shelley agree that shortly after the birth of her first babe a certain insensibility, always latent in Harriet’s temper, began to show itself in peculiar fashion. She lost, almost completely, her interest in books and reading, in intellectual adventures, and even in the domestic responsibilities attaching to her as wife and mother. That Shelley felt deeply this diminution of her customary cheerfulness, this new, strange aloofness of his formerly bright-natured wife, is amply evident from the testimony of his poems and letters. With an aching heart he watched the too rapid course of the chill current of indifference. Sometimes he would turn to the Boinvilles in perplexity and doubt, seeking help for a problem he hardly knew how to voice. [page xxx] In the society of his thoughtful friends he found stimulus for an increasingly dejected spirit, and for the time perhaps succeeded in forgetting Harriet. On her side, no doubt, Harriet also experienced disillusion. She was no longer a fanciful schoolgirl, but a young matron who looked upon her husband’s exceptional views and manners with less partial eyes than before. Now he was reading rapturously with Cornelia Turner in the Italian poets, now debating ardently some religious or political question, now impulsively wandering abroad or losing himself in fantastic abstractions, but she, who had given herself to him for all the time, was not receiving due consideration, and did not feel the necessity of making her gift a progressive one. They were husband and wife, and the wife had no fear of losing the husband. If Shelley hoped to break through this film hardening into a barrier, Eliza’s constant presence, which had become very irksome to him, and Harriet’s 1 carelessness toward Ianthe, made the attempt more and more difficult. Through the advice of her sister and father, too, Harriet was beginning to press for a better social station in life. Was not Shelley a baronet-to-be and heir to a great estate? It was becoming surely apparent that the relation between these two had never been a vital one, but only for a time vitalized. Despite a second marriage ceremony, entered upon March 22 for legal reasons, and despite Shelley’s passive acceptance of duty of patience, Eliza and Harriet, by April, 1814, had taken their departure for a season, and Shelley had written the mournful stanzas printed on page 1. The following month he addressed a poem to Harriet, concluding with appeal: —

“O trust for once no erring guide!

Bid the remorseless feeling flee;

’T is malice, ’t is revenge, ’t is pride,

’T is anything but thee;

O deign a nobler pride to prove,

And pity if thou canst not love.”

1 Harriet’s last letters to Mrs. Nugent, however, contain several very affectionate references to Ianthe.

[page xxxi]

But Harriet remained away, settling now at Bath, while Shelley walked despairingly the streets of London. He called not infrequently the home of his master, Godwin, whose financial condition was even worse than his own, and whom he was devotedly anxious to relieve. One midsummer day he met — probably then for the first time — Godwin’s daughter Mary,1 seventeen years of age, pale, earnest, and beautiful. Their intellectual sympathy was immediate, and after but a month of acquaintance each knew but to certainly the feeling for the other. As yet no word of disloyalty to Harriet was uttered on either side. Shelley did not at the moment believe that an honourable release was open to him, and Harriet, for her part, was now beginning to regret their division. By July, however, Shelley had come into possession of what he thought unquestionable evidence of his wife’s unfaithfulness to him, evidence which he continued to believe, though it was later modified in some important particulars, until he died. Concerning its actual value it is difficult if not impossible to pronounce, but there can be no doubt of Shelley’s pain and sincerity in relation to it. Neither he nor Mary Godwin hesitated to accept what seemed to them a justifying condition of their present love and, indeed, of their later union. Writing to Southey in 1820, Shelley declares himself “innocent of ill, either done or intended; the consequences you allude to flowed in no respect from me. If you were my friend, I could tell you a history that would make you open your eyes; but I shall certainly never make the public my familiar confidant.”

When Shelley, about July 14, suggested to Harriet the desirability of an understood separation, she did not openly oppose him, thinking it probable that his regard for Mary

1 Harriet’s first reference to Mary, in her correspondence with Mrs. Nugent, has pathetic interest: “There is another daughter of hers, who is now in Scotland. She is very much like her mother, whose picture hangs up in his (Godwin’s) study. She must have been a most lovely woman. Her countenance speaks her a woman who would dare to think and act for herself.”

[page xxxii]

Godwin would shortly cease and that he would return to her. This attitude of compliance gave Shelley a wrong impression; he arranged for her material welfare, and withdrew with a feeling that all would be well, and that Harriet concurred in the course he had resolved to pursue. That he was mistaken in this supposition made Harriet’s loss only the more grievous, but both Shelley and Mary believed that the new union was to prove best not merely for them but for Harriet as well, whose “interests,” as he conceived them, Shelley constantly consulted. On July 28, 1814, Mary Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley, accompanied by Clara Jane Clairmont, left London for the Continent, and the next day, at Calais, the poet wrote in his journal: “Suddenly the broad sun rose over France.”

The tour that followed was a brief one, cut short by lack of funds and by difficulties arising in England. While it lasted, however, Shelley and Mary had opportunity to realize the strength and virtue of their love, in a time of physical and mental stress. Spending but a few days in Paris, they proceeded on foot (Mary riding a donkey) to Charenton. There they replaced their little beast by a sturdy mule, and reaching Troyes bough an open carriage. By these means, after many annoyances, they at length arrived at Neuchâtel, and at Brunnen on Lake Lucerne. En route Shelley had written to Harriet, urging her to meet them in Switzerland, and assuring her of his intention to remain her friend. At Brunnen he began the fragment entitled The Assassins, a romantic tale of some power. After a brief stay here and at Lucerne, the travellers turned homeward, following the Reuss and the Rhine. The beauty of the latter river, form Mayence to Bonn, greatly impressed Shelley and influenced scenic setting of Alastor. Rotterdam was reached September 8, and London once again a week later.

During the remainder of the year Shelley and Mary suffered seriously from the want of income. Although Godwin indignantly refused to condone Shelley’s course, he [page xxxiii] freely accepted money from his scant purse and even asked for more. There is no unconscious dramatic irony lurking in a passage concerning Godwin in one of Shelley’s early letters to Miss Hitchener: “He remains unchanged. I have no soul-chilling alteration to record of his character.” Harriet, too, was losing patience and troubling both Shelley and the Godwins with increasing demands. ON November 30 she gave birth to a boy, Charles Bysshe, who, with Ianthe, was soon to become the subject of Chancery litigation. Peacock was proving himself and old friend; Fanny Godwin was secretly kind; but for the most part Shelley and Mary were let severely alone save for the companionship of Hogg, who called often, and Jane Clairmont (Claire), who declined to return home. Omnivorous reading solaced the evil time, — Anacreon, Coleridge, Spenser, Byron, Browne of Norwich, Gibbon, Godwin, etc. Claire, alert and olive-hued, often disturbed the household with her fears and doubts concerning the supernatural, and they were not unrelieved to see her depart, in May, 1815, for a stay in Lynmouth. Shelley, for his part, had other fears, and was now moving from spot to spot in London, protecting himself as he might against the vigilance of the bailiffs. The new year brought important changes. Sir Bysshe had passed away on January 6, Mr. Timothy Shelley became a baronet in his stead, and the poet succeeded his father as heir-apparent to the title of a great estate. He went down to Field Place, but was not welcomed. The question of entail again came up, and though Shelley declined to change his attitude, he was willing to sell his reversion. Eventually he planned to dispose of his interest in a small part of the property for an annual income of ₤1000 during the joint survival of his father and himself, but Chancery would not later permit this plan to be realized. Money was advanced to meet his most pressing needs, and it is worthy of note that he immediately settled ₤200 a year upon Harriet, a like sum having been continued by Mr. Westbrook. [page xxxiv]

Shelley’s health had of late become seriously impaired, and was not improved by the shock consequent upon the death, March 6, of Mary’s first infant, hardly more than a fortnight old, and by the continued alienation of Godwin, whom he was aiding steadily. He bore Godwin’s bitter letters very patiently save for one final outbreak of feeling: “Do not talk forgiveness again to me, for my blood boils in my veins, and my gall rises against all that bears the human form, when I think of what I, their benefactor and ardent lover, have endured of enmity and contempt from you and from all mankind.” A trip of several days’ duration up the Thames to Lechlade, in the company of Mary, Peacock, and Charles Clairmont, Claire’s brother, did much to restore the poet to health and good spirits. On his return to Bishopgate he conceived and that autumn wrote the moving revelatory poem, Alastor, the first of his really sure and vital works, published the following March. Peaceful months followed, of study and composition, whose sunshine was made the brighter by the birth of William, Mary’s second child, January 24, 1816. But Godwin’s attitude, the coldness of others, and the failure of the lawyers satisfactorily to adjust financial matters, — he was again dependent upon his father’s voluntary advances, — led Shelley to heed the invitation of a voice of whose charms he could no longer be insensible. It was Switzerland’s recall of him that he heard and obeyed. Byron, whom he had not yet met, but with whom Claire had become only too well acquainted, was soon to arrive to Geneva, and the infatuated girl, keeping her secret from Shelley and Mary, asked and was permitted to become one of the party. Early in May, 1816, the trio, with little William, started again for Paris. They reached Geneva about the 14th, and shortly afterward Byron appeared. The two poets, though associated as contemporary apostles of revolution, were yet of very different fibres, — Byron, proud, passionate, fitfully purposive, like an alien bird oaring and flapping close to earth; Shelley, keen, [page xxxv] luminous, mild, sun-adventuring, sailing the upper ether of thought and love with tense but tireless wings. Each knew the other for a poet, — Shelley had drawn the two portraits for us in Julian and Maddalo, — and they spent eager hours together with Polidori, Byron’s young Anglo-Indian physician, cruising about the lake, or exploring its shores. During this time Byron wrote some the best stanzas of his Childe Harold, Shelley conceived his Mont Blanc and Hymn of Intellectual Beauty, and Mary began her famous romance, Frankenstein, inspired by a ghostly conversation between poets and Polidori. The Shelley group had meanwhile secured a cottage near Coligny, and Byron was living at the Villa Diodati. While they circumnavigated the lake, Byron produced his Prisoner of Chillon and Shelley stored up countless memories of joy and beauty. After a visit of high emotion to Chamouni, Shelley and Mary received a rather melancholy letter form Fanny Godwin, and a month later left Geneva for Versailles, Havre, and Portsmouth.

The year 1816 was a fatal one for several of Shelley’s friends and connections. The death of Sir Bysshe was followed during the autumn by those of Fanny Godwin and Harriet Shelley, each of these women dying by her own hand. Fanny, who had been growing of late more and more dejected, feeling the unkindness of her stepmother and other relatives, and deprived of the immediate counsel of Shelley and Mary, decided she was a useless cumberer of the ground, and took laudanum at Swansea, October 10. She had written only a week earlier an affectionate letter to Mary who with Shelley now staying at Bath, in which all her thoughts unselfishly went out to the welfare of Godwin and the Shelleys. These were her sincere mourners. “Our feelings are less tumultuous than deep,” wrote Godwin to Mary; and she to Shelley, who went to Swansea suffering great anguish of spirit: “If she had lived until this moment, she would have been saved, for my house would [page xxxvi] then have been a proper asylum for her.” Two months later the body of Harriet was found in the Serpentine River, after a disappearance of three weeks. She had, even as a schoolgirl, remotely contemplated such ending, and now, with Shelley gone (though he was at this very time seeking her anxiously, that he might relieve her distresses), with her father and sister angered against her, and with a last friend unwilling longer to forward her happiness, she took the plunge with a despairing calmness. If she had wandered morally, she felt at least as justified as Shelley himself, whose social views were not capable of a uniformly beneficent application t concrete cases. Love, as she understood it, seemed indeed, by harsh evidence, thrown from its eminence. Yet her death was far less the specific outcome of Shelley’s conduct than it was the due result of a fatal flaw in her own character, and though Shelley felt acute and abiding regret, he cannot be said to have experienced remorse. We may briefly compare, in passing, the matrimonial beginnings with Shelley with those of his grandfather, and note the untimely closing of the waters over Shelley’s head as over Harriet’s. We must pass rapidly over the accompanying and dependent events of this season, — the renewal of old friendships, Godwin’s persistent difficulties, the generous literary encouragement of Shelley by Leigh Hunt, the reconciliation of Godwin to the poet, and the formal ceremony of marriage between Shelley and Mary at St. Mildred’s Church, London, December 30.

The care of his children, Ianthe and Charles Bysshe, had been reluctantly and at her earnest request committed to Harriet by their father, who now sought to gain possession of them. His right to do so was stoutly contested by the Westbrooks, who filed a suit in Chancery to determine the question. They represented that Shelley, as the deserter of Harriet and the author of Queen Mab, was not a proper person to have control of the children’s upbringing and education; while Shelley’s counsel argued that the poet [page xxxvii] was justified in leaving Harriet, and that he had since that time faithfully supplied her needs, while it were intolerable tyranny to wrest his children from him merely on account of intellectual conclusions. After two months of legal conflict the case was decided against both parties, Lord Eldon postponing the final judgment until July 25, 1818, but declining to grant the custody of the children to either Shelley or Mr. Westbrook. At length it was determined to place Ianthe and Charles in the care of Dr. and Mrs. Hume, of Brent End Lodge, Hanwell, persons nominated by Shelley and paid chiefly by him and partly by the interest of a fund previously settled upon the children by Mr. Westbrook. Shelley keenly felt the injustice of the judgment, but preserved a fine attitude throughout the proceedings. During this time he and Mary, with their child William, were for the most part resident at Marlow on the Thames. Before going thither, however, Shelley met Keats, Hazlitt, and also Horace Smith, who became a close friend and sympathizer. At Marlow he spent more than a year of busy authorship, hospitality, and beneficence. As writer, he produced, among other pamphlets and poems, some remonstrant lines to Lord Eldon, Prince Athanase, part of Rosalind and Helen, and Laon and Cythna, — afterward The Revolt of Islam, — a stirring and eloquent prophecy of the triumph of the spirit of love and liberality. “I have attempted,” he wrote to his publisher, “in the progress of my work to speak to the common elementary emotions of the human heart, so that though it is the story of violence and revolution, it is relieved by milder pictures of friendship and love and natural affections.” As host, he entertained Peacock, Godwin, the Hunts, William Baxter, and Horace Smith, besides Claire and the little newcomer, Clara Allegra, daughter of Byron. As friend and helper, the poor of Marlow knew and loved him. On September 2, 1817, after the completion of Frankenstein, a third child was born to Shelley and Mary, whom [page xxxviii] they named Clara Everina. Godwin’s well-known novel, Mandeville, appeared during November, and Shelley corresponded freely with its author as both admiring critic and purse-opener.

“I think we ought to go to Italy,” wrote restless Shelley to Mary late in 1817, after much discussion both ways and means. Shelley’s failing health, medical advice, Mary’s own inclination, and the desire to help Claire toward an understanding with Byron, all conspired to this end. March 12, 1818, saw the travellers once again — for Shelley now the last time — leaving the cliffs of Dover for Calais. Had the poet known that he was to see his native land no more, his hearth would have gone out to her in a high song of farewell, for despite his passionate desire to compass the reform of many of her laws and institutions, his life and letters at many points affectionately attest the strength of his love for England.

The four closing years of Shelley’s brief life were the happiest and most productive. Indeed, had these been denied him, his works would hardly have won large place in the memories and affections of men. Animation was his, bright and breathless; power was his, earnest and unmistakable; but time and place were yet to bring their calm and their counsel to his too agitated spirit. What the clear sunny skies of Italy had done for Chaucer and Milton, what they were to reveal to Browning and his lyric love, they were now about to give to Shelley in abundant measure, and thereafter to keep protective watch above his cloverclustered Roman grave.

The passage of the Alps was safely achieved, and the travellers reached Milan, April 4. Thence Shelley and Mary proceeded to the Lake of Como, but, disappointed by their continued failure to find a suitable abode, they returned to Milan, shortly gathered their little flock together, and pressed on to Pisa and Leghorn, not, however, before Claire had satisfied the demand Byron made from Venice that she [page xxxix] should relinquish to him the control of Allegra. At Leghorn they gladly met Mr. and Mrs. John Gisborne, the latter of whom, a bright, thoughtful woman, was an old friend of Godwin’s, and the mother of Henry Reveley, Gisborne’s stepson. After a few weeks in Leghorn, Shelley transferred his family to the Baths of Lucca, in the beautiful forest country north of Pisa. Here Rosalind and Helen was concluded, and here husband and wife spent memorable hours in the groves and vineyards, within sight of Apennine summits. This life of calm was broken by the growing anxiety of Claire, whom Shelley at length accompanied to Venice to see Byron and Allegra. Claire found her little daughter at the home of the Hoppners, the English consul-general’s family, who received the wayfarers with great hospitality. Shelley alone visited Byron, who heard him with friendly regard, but with little real consideration. He stressed his liking for Shelley, however, and insisted that he bring his family and Claire to live for the time in Byron’s then unoccupied villa — I Cappuccini — at Este, among the Euganean Hills. Shelley accepted the invitation, and wrote to Mary asking her to meet him in Este. Little Clara was taken ill on the road, and after anxious days in the new home, the parents hastened with her to Venice to consult there a noted medico, but had hardly arrived when the child died. A week passed sadly in Venice before they returned to Este to find Claire again, William, and Allegra. Now for some time having brooded his masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound, Shelley fell back upon present surroundings and recent memories, first producing Julian and Maddalo, and, in part at least, Lines Written among the Euganean Hills. The latter poem is poignant and almost incredible lyric beauty; the former has been already touched. By October 12, the poet, with Mary and William, was back in Venice, seeing much of Byron, admiring his genius but despising his excesses. After a brief return to Este and the re-delivery of Allegra to Byron, the hospitable villa was deserted and the faces of the four were [page xl] set southward for Naples. Here, notwithstanding his hope of improvement, a deep dejection, both physical and spiritual, seized upon Shelley, an almost Hamlet-like sense of isolation, from which he did not well recover until the early spring. It was now resolved to visit Rome, where they had spent but a week en route to Naples, and the completion of their first year in Italy was signalized by the entrance of the pilgrims into the Eternal City. They found themselves now somewhat less lonely; acquaintances called; steady reading went on; and interested visits were paid to the Vatican, Villa Borghese, Pantheon, and Capitol. In the remote and solitary moments of his frequent walks about the ruins of the Baths of Caracalla, Shelley almost completed his great lyrical drama, Prometheus Unbound, among at once the gentlest and proudest vindications of the human spirit. He felt his inevitable way to the symbolic heart of this noble myth, as imagined and made vital not only by Æschylus and others, but by the high instinct of man he had himself developed. Here Shelley’s prime idea of the self-saving and self-justifying power of Love reaches its surest and most elevated expression.

A long reaction and an anticipation of evil to come led the poet to long again for at least a brief visit to England, “out of pure weakness of heart.” The temperamental barometer proved true. On June 7 William, the most fondly cherished of the children, passed away. The English burying-ground, hard-by the Porta San Paolo, received the little body, and Shelley and Mary were left desolate indeed. The mother’s melancholy, in truth, became so intense that Shelley decided upon Leghorn and Mrs. Gisborne as the place and person most suited to her at the moment, and rented, accordingly, the Villa Valsovano there. He himself had urged his doubtful steps through many a gloom, and felt for the thrice-bereaved mother no less than he felt with her. “We must all weep on these occasions,” wrote Leigh Hunt to Mary, “and it is better for the kindly fountains within us that we [page xli] should. May you weep quietly, but not long; and may the calmest and most affectionate spirit that comes out of the contemplation of great things, and the love of all, lay his most blessed hand upon you.” When Mary would be much alone Shelley read and though as rapidly and eagerly as ever, adventuring through Dante, Boccaccio, and Calderon, and praising the Spanish dramatist with discriminating enthusiasm. Now, too, he finished his own deeply stirring drama, The Cenci, conceived more than a year before, after reading an old MS. at Leghorn and viewing Guido’s supposed portrait of Beatrice in the Colonna Palace at Rome. This production, touched as it is with weaknesses of phrasing and of dramatic “business,” — the dramatist sometimes hinders the poet, — is yet comparable, as a study in the spirit of hate and villainy, only with Shakespeare’s Richard III and Browning’s Guido; while Cordelia, Pompilia, and Beatrice form the triad of great women in English poetry. The fifth act is by far the most powerful, not only because it contains the “tremendous end,” but because Shelley raises here a nigh unfettered wing in soul-criticism and dramatic range.

In Florence, where the autumn of 1819 found them settled, Shelley spent many days visiting the great galleries of painting and statuary, though with increasing physical unrest. On November 12 a last child was born to him, christened Percy Florence, who survived both his father and his mother, and inherited due baronetcy. The prevailing discontent in England, with which Shelley deeply sympathized, occasioned at this time the writing of his Songs and Poems for the Men of England, and his Masque of Anarchy, — poems of peaceful poise but revolutionary impulse, — and a thoughtful treatise, A Philosophical View of Reform. A translation of Euripides’ The Cyclops, the creation of the Prometheus, and the breathing of the subtly lyric incantation to the spirit of the West Wind, all belong to this great creative year. It is interesting to note the loyal [page xlii] human interest Shelley took during this winter in his friend Reveley’s projected steamship, an interest that did not hesitate to provide ill-to-be-spared money for the advancement of what was almost a foredoomed failure. The extreme cold of early January 1820, drove him at length to Pisa, where most of his time was thenceforth to be spent. A small group of friends cheered Shelley and Mary here, during the few intervals not give over to study and composition, — friends not unwelcome, since the Gisbornes and Henry Reveley were now leaving for England. Though the poet’s health was responding favourably to the change of climate, Godwin’s monotonous embarrassments and demands preyed upon his spirits, and he was obliged to protect Mary from full knowledge of her father’s rapacity. There were other sources of perplexity and even anger that greatly disturbed the Shelleys at this time, — a grossly unfair attack upon the poet in the Quarterly Review, and a scandal spread abroad by a vicious servant which it took some time to check and refute. With the advent of midsummer the heat grew so intense that a move was made to the proffered home of the absent Gisbornes, Casa Ricci, in Leghorn, where — following the Pisan lyric, The Cloud — the Ode to a Skylark was written. Probably the music of the Spenserian Alexandrines, for he had long loved the Faerie Queene, rang in Shelley’s ears as he penned this exulting yet regretful cry. Among the other poems of 1820 are the Letter to Maria Gisborne, The Sensitive Plant, The Witch of Atlas, Hymn to Mercury, Ode to Liberty, and Ode to Naples. By August, the heat was unbearable, and another change was made to the Baths of San Giuliano di Pisa. Shelley’s interest in European political conditions was acute, and he watched with keen solicitude the course of the revolutions in Spain and Naples, greatly regretting the eventual success of the Austrians in restoring the false Neapolitan king. During the early months of 1821 he sought and found social reinforcement of his views. The [page xliii] Gisbornes were back, though a lively misunderstanding prevented an early renewal of old ties; and Thomas Medwin, the poet’s cousin and former schoolmate, had found his not too welcome way to Pisa. Over against these was the finer intelligence and exalted spirit of the Greek patriot, Alexander Mavrocordato, to whom Shelley’s prophetic drama, Hellas, was afterward dedicated; the finesse of Francesco Pacchiani, a Pisan academician; the good-natured vapidity of Count Taaffe; the skilful improvisations of the famous Sgricci; and the pathetic durance of the Contessina Emilia Viviani, beloved alike by Shelley, Mary, and Claire. Condemned, with her sister, to the strict seclusion of a convent life by a jealous stepmother and an indifferent father, Emilia was in evil case, and this, with her exquisite loveliness, so wrought upon Shelley’s imagination that he sought continuallyn to deliver her from the Intolerance he had so often scourged of old. He became her “caro fratello” and Mary her “dearest sister.” The profound though passing influence exerted upon Shelley by her character and situation is apparent in his Epipsychidion. “It is,” he wrote to Gisborne, after many months, “an idealized history of my feelings. I think one is always in love with something or other; the error — and I confess it is not easy for spirits cased in flesh and blood to avoid it — consists in seeking in a mortal image the likeness of what is, perhaps, eternal.” The “isle under Ionian skies,” and idea which had so strong a hold upon Shelley’s fancy,1 as upon the youthful Browning’s,2 here achieves its right poetic value. Emilia married at last a Signor Biondi, and lived but a brief and checkered life. It was fitting though almost accidental

1 Cf. letter of August, 1821, to Mary: “My greatest content would be utterly to desert all human society. I would retire with you and our child to a solitary island in the sea and build a boat, and shut upon my retreat the floodgates of the world.” Cf. also Prometheus, IV, iv, 200,201.

2 Cf. Pippa Passes, ii, 314-327.

[page xliv]

that at this time Shelley should put into critical form his own noble theory of poetry, published after his death.

Soon after the departure of Claire, who was now engaged in tutoring certain young Florentines, there arrived in Pisa friends of Medwin, Lieutenant Edward Elliker Williams and his wife Jane. The Shelleys, both husband and wife, were much pleased with the newcomers, who in their turn attached themselves with sympathy and understanding to their fellow-exiles. With Williams and Reveley the poet would sail the Arno in a light Arthurian shallop that on one exciting occasion suddenly overset, nearly ending Shelley, the non-swimmer, then and there. Notwithstanding this mishap his love for nautical excursions grew into a passion, nearly every day found him on the water, and May 4, he even undertook a venturesome excursion with Reveley from the mouth of the Arno to Leghorn. In San Giuliano the case was not different, and it was there, indeed, that the

Boat on the Serchio was born. Here also was produced the last of Shelley’s completed major poems, Adonais, written in memory of John Keats.

Upon hearing of Keats’s illness and of his arrival in Italy, Shelley had urged him to accept the invitation to Pisa he had previously extended, but poor Keats was already struggling with death, and yielded himself at Rome, February 23, 1821. Shelley received the news some weeks later, probably a letter from England, and began almost immediately to brood his elegy. He had not known Keats well, had variously estimated his work, and had scarcely sympathized with his consuming passion for his art. Indeed, he had written Keats an earnest word concerning his own freedom from “system and mannerism,” instancing the Prometheus and The Cenci. Over-regularity he had sought to avoid. “I wish those who excel me in genius would pursue the same plan.” And Keats had good-humouredly replied: “An artist must serve Mammon; he must have ‘self-concentration’ — selfishness, perhaps. You, I am sure, will forgive [page xlv] me for sincerely remarking that you might curb your magnanimity, and be more of an artist, and load every rift of your subject with ore.” Shelley did not much admire Endymion, but he though Hyperion “grand poetry,” The product of “transcendent genius.” He sincerely respected Keats, though he failed to understand him, and it is matter for large regret that the two poets, because of the sensitiveness of the one and the too lately aroused concern of the other, did not find a closer union — a communion — possible. The poem itself, written in Spenserians, is a pure elegy unequalled in our language. It sounds the deeps of death, for Keats, for Shelley, for all “the inheritors of unfulfilled renown.” It was first printed at Pisa, with the types of Didot. “I am especially curious,” wrote Shelley to his English publisher, Ollier, “to hear the fate of Adonais. I confess I should be surprised if that poem were born to an immortality of oblivion.”