ERRATA

LOCATION | ERROR |

page 5, 15.7 | ‘no’ changed to ‘not’ |

[handwritten: Pamph.

I.E.

C.]

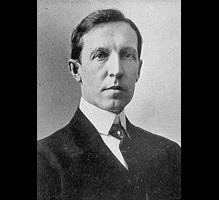

A SEQUEL TO ‘CHRISTABEL’ [handwritten: (by E.J. Chapman)]

A Review by L.

MAY, 1899. [unnumbered page]

We have sent this Review to the writer of the book of poems mentioned on the opposite page, with full authorization to make it public should he care to do so.

L.

[unnumbered page]

A SEQUEL TO ‘CHRISTABEL.’

[‘A Drama of Two Lives,’ ‘The Snake-Witch,’ and other poems, by E.J. CHAPMAN, late of the University of Toronto. London: Kegan Paul & Co. 1899.]

A REVIEW, BY L.

SEQUELS are proverbially failures: what then can be said of a recent bold attempt to produce a sequel to one of the most imaginative and melodious of English poems—the mystical, soul-stirring ‘Christabel’ of Coleridge’s dreamy muse? Truly, as a reviewer puts it, the attempt is at least a proof of courage on the author’s part: and, although the critic does not actually quote Pope’s well-known adage, his dictum evidently infers that such might be applied, not unfitly, to the present case. And, apparently, he does not stand alone, as some other captious notices in literary journals have sought to depreciate our author’s work, although without venturing to corroborate their adverse judgement by a single line of quotation. This may be quite orthodox, but it seems hardly fair to either author, publisher, or readers—[unnumbered page] giving the latter no opportunity to exercise their own judgment in the matter.

Seeing these notices and criticisms, we were naturally led to assume that Mr. Chapman’s verses, and more especially his continuation of ‘Christabel,’ might be justly relegated to that limbo of unhappy authorship to which, year after year, so many ephemeral and abortive attempts at verse-making naturally find their way. Meeting, therefore, with the book at the country house of a literary friend, we were preparing to make merry over it, when our friend, speaking, to our surprise, very much it its favour, asked if we had read it? ‘Why, no!’ was the reply; we hardly thought it was worth looking into, after what certain critics had said of it. ‘A fig for critics!’ cried our host; ‘read it over your cigar to-night, and perhaps your opinion may undergo a change.’ And so the little book was read, and re-read; and our opinion has certainly undergone a most undoubted change. But in these remarks we refer practically to the ‘Snake-Witch,’ the longest poem in the book. This is an attempt to form a conclusion to ‘Christabel,’ in the style and versification of the original poem; and so, perhaps, naturally enough, it has aroused the critics’ ire. As a continuation of Coleridge’s unfinished poem, it very property, indeed necessarily, strives to carry out in [page 4] sentiment and metre the spirit of that imperishable fragment. The critics attempt to decry it because they say it is an ‘imitation.’ But what would they have? To some extent it is of course an imitation; but if by the word imitation they mean plagiarism, we beg to differ from them totally; and all who will honestly go through the poem will come, we are sure, to our conclusion. A successful completion of any unfinished work of art, whether poem, or painting, or musical score, or what not, must necessarily seek to carry out the conception of the original worker. The one mind must be able to understand and enter into the spirit of the other— ‘Du gleichst den Geist den du begreifst,’ says Goethe, truly—and the result must necessarily be an imitation. Have we not accepted, if unacknowledged, imitations in our literature, even in that of modern times? But, although in the ‘Snake-Witch’ the attempt is made to adopt the inspiration and tone of thought, and rhythm, of the older singer’s work, the imitation, as already said, is totally distinct from plagiarism. It bears much the same relation to the verse and narrative of ‘Christabel’ as the ‘Sestiads’ of the old Elizabethan poet, George Chapman, bear to Marlow’s ‘mighty line,’ in his completion of the dead poet’s ‘Hero and Leander.’ It is this that the critics have refused to see, probably owing to a [page 5] too cursory examination, combined with a foregone conclusion that the audacity of an outsider in attempting to complete the unfinished ‘Christabel’ must be frowned down at all cost. If, in one or two places, a word or thought purposely recalls (as occasionally necessary) an incident or expression of the original poem, the fact is invariably indicated, although, we think, quite unnecessarily.

The points which chiefly force themselves on the reader’s attention in the perusal of the ‘Snake-Witch,’ are, first, the complete Coleridgean spirit which pervades and permeates almost every line, even when the incidents and scenery of the older and newer poems are quite distinct; and, secondly, the unbroken lyrical flow and melody of the verse. These points may be illustrated (before giving a more detailed analysis of the poem) by a few brief extracts, taken at hap-hazard from different pages:

‘Huddled close, with blinking eye,

The owls awake on the castle wall—

From cliff and crag the night-jars call—

Each answers each with hoot and cry,

With cry and hoot they answer, all!

The black-wing’d bats whirl darkly by—

In fever’d gusts the night-winds blow—

Above, the black pines surge and sigh,

The black stream sobs below:

As ever it goes on its gleamless way [page 6]

Through miles of forest—far and far—

Touch’d by never a tender ray

Of sun or moon or circling star!

* * * *

The midnight storm has roll’d afar,

The pale dawn pearls the opening skies,

And one by one each waning star

Within the opal’d orient dies.

Low on the line of sky and lake

The red moon floats with horns atop—

But only the owls are yet awake

To watch the red moon drop and drop.

* * * *

The night is over, the noon has come,

The forest is full and wild bees’ hum,

And faint but clear, and soft withal,

Comes from afar the cuckoo’s call.

* * * *

But now the walls are weak and grey,

And crumbling ever in slow decay:

The trailing roots of the maiden-hair

Have thrust the stones apart, and there

The red-lipped lichens cling alway:

But still, as in the olden day,

When Spring awakes, and lawn and lea

Are bright again with petall’d gold,

The swallows come across the sea

As came they in the days of old.

Its love-song still, on budding thorn,

The brown-fleck’d throstle pipes anew,

When throbs the earth’s awaken’d morn,

And leaves are green, and skies are blue!

But long has Langdale’s glory flown— [page 7]

With roofless halls, untenanted

Save by the ghosts of days long dead,

The old grey ruin stands alone,

A thing forlorn! The forest hoar,

And all the old times’ wonder-lore,

One and all are dead and gone,

Dead and lost for evermore!’

In the original poem, it will be remembered, after the discovery of the false Geraldine in the forest by Christabel, the ghastly night in Christabel’s chamber, and the fascination of Sir Leoline by the glamour of the Witch’s presence, when the memory and early friendship of her asserted father, the Lord of Tryermaine, are depicted in those memorable lines beginning with— ‘Alas! they had been friends in youth!’ —that no lyrical poet has yet approached—the narrative portrays the fearful intuition of Christabel, her father’s unreasoning anger, and the enforced departure of Bard Bracy to carry the news of Geraldine’s safety to Tryermaine. It then breaks off, ending at the close of Part II. with the lines:

‘Why Bracy! dost thou loiter here?

I bade thee hence! The Bard obeyed;

And turning from his own sweet maid,

The agèd knight, Sir Leoline

Led forth the lady Geraldine!’

Christabel: Part II

In the ‘Snake-Witch,’ Mr. Chapman’s conclusion to [page 8] ‘Christabel’ —equivalent, virtually, to Part III. of that unfinished poem—the narrative opens with the coming up of a wild storm in the rapidly closing day:

‘The wolves’ long wail in the ghastly light

Drifts drearily through the forest-moan!

* * * *

In trailing wrack the clouds are borne

Across the black and starless sky;

Black above, and black below,

The pointed pine-tops hardly shew

Against the gathering night behind!

Loud and louder moans the wind,

Like fetter’d beast that strives in vain

To rend and gnash its galling chain:

Now in wild rushes—in wailings now—

A wild night cometh apace, I trow!’

Passing over some passages of considerable power, we are then introduced to the unhappy Christabel in her solitary chamber:

‘Half-way up the turret-stair

In her maiden chamber fair,

Silent as a nun that sits

In the silence of her cell,

Sits the lady Christabel!

The bat without in gloaming flits,

And she has sat there all day long

Since the lark’s unloosen’d song

Rippled through the reddening morn.

A weary creature, crush’d forlorn,

As one that in a ghastly dream[page 9]

Forlorn and helpless doth espy

The dull cold hate of an evil eye,

And cowering shrinks beneath its spell:

So shrinks the lady Christabel!

* * * *

As swathèd corpse beneath its pall,

Was she beneath that deadly thrall,

Cowering crush’d and helpless there!

* * * *

The stormy sunset’s lurid glow,

Across the carvèd Christ upthrown,

Hung blood-like on the tortured brow

Engirdled thick with thorny crown,

As wearily she sank adown

Before the Holy Rood to pray—

* * * *

So, from the darkening earth and sky

The long day waned—the night fell drear—

When wildly with a shivering cry

Of loathing and of ghastly fear,

In terror to her feet she leapt:

A snake’s low hiss appall’d her ear,

A snake’s cold touch across her crept!

And as she rose there came a sound

Of leaves wind-trail’d on wintry ground—

. . . .

A viewless horror hung about,

Through the thick air a silence fell,

Save when the wind’s moan moan’d without

To the weary moan of Christabel!’

The voice of the dead mother breaks the spell, and Christabel is bidden in all haste to seek the [page 10] aged Hermit, her mother’s friend of old days, who lives a solitary life among the hills:

‘Where scatter’d rocks lie thick between

The mountains grey and the forest green,

And girt with hoar pines, rent and sere,

Through clinging mists the echoing fell

Looms dark above the lonely mere.’

The introduction of the mediæval Hermit into the poem is one of Mr. Chapman’s innovations, perhaps not wholly to be commended; but it has one merit, that of bringing into the poem a touch and colour of the love-element, a tone of emotional tenderness and passion, singularly wanting in the original ‘Christabel.’ Some vigorous lines depict the wild night-ride of the hapless maiden through the lonely forest, and her meeting with the Hermit in his cell. By way of episode, the past life of the latter is brought before us. How he had known the dead mother in her girlhood—had secretly loved her—and on her marriage to another, had thrown up his knightly career and retired to his lonely cell, after the manner of orthodox hermits of mediæval romance. Time goes on, and the two again meet and renew their loyal intercourse. And so, after awhile,

‘. . . . though never word was said,

The secret of his soul she read

Across its silence—’ [page 11]

Then comes again the parting hour: this time, for all time:

‘But soon he stood again alone!

Ere yet the first spring-buds had blown,

Low he knelt at the lady’s side,

With heard bow’d down in silent prayer

Beside the wan face lying there:

And on her dead, cold hand did press

A lingering first and last caress,

By death’s great parting sanctified—

. . . .

Betwixt the darkness and the day,

Whilst life and death inwoven were,

The Mother of God came softly there,

And bore the sinless soul away!’

Her remembrance lingers with him ever—

‘Through months and years, till life became

The phantom of a memory

That clung and clung, and would not die.’

We have taken some liberties in transposing portions of our author’s poem, here and thee, in order to render our condensed and necessarily somewhat broken narrative more clear to the reader; and we must now go back a page or two, so as not to pass over the very powerful and pathetic lines in which the Hermit first appears to us:

‘In fitful sleep the Hermit lay

All night within his chamber lone, [page 12]

Wrought and carved in the bare grey stone;

And in his dream there came always

A white-robed ghost that spoke no word

But whose pale glance his pulses stirr’d

As in the old days, long ago!

. . . .

O false dream, darkening Hope’s eclipse—

It was their bridal prime, he thought:

Day purpled into night—their lips

Each other in the darkness sought,

And meeting silently were press’d

In one long clasp, that clung, and drew

Soul into soul! If false or true,

He heeded not—he only knew

They were all one in that unrest

That held him with its vampire spell,

Till fled the faithless dream away,

And on his heart the dead hope fell

As falls upon a corpse the clay—

And through the night, and through the day,

Ever it came, the voice that said

With ceaseless mock, it better were

O fool, for thee, that thou wert dead,

Than live to fix thy love on her!’

Now, where, it may be asked, does the asserted imitation here come in? We cannot help suspecting, very strongly, that if the above lines—so full of tenderness and musical flow—had been written by a known hand, there would have been no stint of praise on the part of our critics, and no talk of imitation. Where Mr. Chapman has perhaps done himself wrong, [page 13] is in publishing verse of this undeniable merit as a continuation or addition to another’s work, in place of weaving it into a distinctly independent poem of his own.

In his life of Coleridge, Mr. Gillman makes the following statement: ‘The second Canto (or Part, as Coleridge calls it) ends, it may be remembered, with the dispatch of Bracy the Bard to the castle of Sir Roland. Over the mountains the Bard, as directed by Sir Leoline, hastes with his disciple; but, in consequence of one of those inundations supposed to be common to the country, the spot only where the castle once stood is discovered, the edifice itself being washed away. He then determines to return.’ There can be no question, we think, that Mr. Chapman’s very striking dénouement of this portion of the story is far more powerful and dramatic. And here, again, we might ask, where does the want of originality come in? De Bracv reaches the castle or Tryermaine with his companion as night is settling down upon it. He finds all dark and desolate without the walls, and the inner courts deserted. A red gleam alone appears at the chapel windows, and from these there rises on the night the crooning of a ghostly dirge:

‘Tryermaine’s walls stood strong and high,

Black they stood against the sky, [page 14]

By tower and turret darkly crown’d!

Many a mile along the land

The salt sea-marshes girt them round

With wastes of ooze and drift and sand,

Where sounds the bittern’s blooming cry,

And sad winds moan, and ceaselessly,

As beat of pulse in living thing,

Comes and goes with its rhythmic swing

The sullen roar of the restless sea.

No banner waves from keep or tower,

No challenge comes from gate or wall:

Still and dark is the lady’s bower,

Still and dark the banquet hall.

Only the chapel windows throw

Across the night a crimson glow;

And through them weirdly floats and falls

The low wild croon of a ghostly dirge—

Afar, at fitful intervals,

The wandering bittern hoarsely calls,

The night-wind wails along the walls,

And thunders ever the breaking surge!’

Their bungle-summons remaining unanswered, they tether their frightened steeds, and make their way across the lonely courts and halls, the doors, by magic influence, opening before them. Suddenly, a curtain being drawn aside by unseen hands, they come upon the interior of the pillared chapel, illumined by countless torches, with black-cowled monks and kneeling sisters surrounding a flower-decked bier, on which rests the body of a young girl with the shadow of the Holy Rood falling across it: [page 15]

‘Loud on the night our bugles rang

Quick answering back, with iron clang,

The drawbridge drops across the moat,

And whilst the bugle echoes flat

In faint and fainter tones afar,

The castle gates swing back: but none

Warder or henchman, never one,

Comes forth our way to guide or bar.

We cross’d the moat and tether’d well

Our steeds that shook with strangest fear

As though some loathly thing were near;

Whilst through the night the castle bell

Toll’d and toll’d its ghostly knell,

And the weird death-chant rose and fell

In measur’d cadence, mournfully,

And so with wavering steps did we

Pass onward trough the courtyard bare,

Where none to meet or greet us were,

And through the gloom of chambers vast,

So long, a curse seem’d on them cast,

So ghastly cold and still were they;

Until a faint and trembling ray

Beneath a sculptured doorway shone,

And led our wondering footsteps on.

The curtain that across it hung

By hands unseen was drawn aside,

The door upon its hinges swung

And the vast chapel high and wide,

In sheen of gold and pillar’d pride

Stood open to our startled gaze!

Around it, countless touches blaze,

And black-cowl’d monks in long array,

And weeping sisters kneel and pray. [page 16]

And ever the death-bell toll’d and toll’d,

And ever it rose, the chanted prayer

For the white wan corpse, so quiet and cold,

In its death-slumber sleeping there,

Behind the bier, the Holy Rood

With its crown’d Christ by the altar stood:

Across the dead its shadow fell,

Across the face so young and fair:

And ever it toll’d, the passing bell,

And ever arose the chanted prayer—

Mary! benedicite!

A sinless soul has flown to thee:

Hear our prayer, and give it rest

On thy sinless, sainted breast!’

This is the dead Geraldine, the daughter of the Lord of Tryermaine, whom the Snake-Witch had personated to Christabel and Sir Leoline. Near the bier, haggard, and shaken with palsy, sits the old father:

‘Near by, against the altar-stone

An old man, silent, sat alone;

White-faced and haggard, with white hair,

And eyes whose dazed and piteous stare

Was like a dead man’s wondering look:

And all his frame with palsy shook.

But as I gazed, and gazed again,

I knew the lord of Tryermaine

Was he who sat in silence there,

So changed and wreck’d and wan with care.’

De Bracy then approaches reverently, and delivers [page 17] Sir Leoline’s message—little thinking that the dead girl beside them was the Geraldine whose safety in Sir Leoline’s castle he was sent to communicate. Here, reference is necessarily made to the earlier portion of ‘Christabel,’ in which Bracy receives his instructions from the Baron, and these are given, as assuredly they should have been, in words that closely echo the Baron’s charge:

‘Then, with obeisance duly made,

I stood before his seat, and said:

I am bard Bracy of Langdale

Sent by my lord, Sir Leoline,

To hasten without let or fail

And say thy daughter Geraldine

Is safe and free in Langdale tower.

His bids thee come in proud array

With all thy men and knightly power

To bear her back to Tryermaine.

And further, doth my lord avow

That he repents the fierce disdain

That urged his words in days that now

Have long gone by. For never yet

Since that far day, can he forget

The friendship lost, the longing vain,

The Past, and all its growth of pain.

This doth the Baron say to thee,

In love and all true loyalty,

Thou gracious lord of Tryermaine!’

The old lord’s answer, and the scene that follows—the ghastly snake-bite in the dead Geraldine’s throat, [page 18] the escape of De Bracy and his companion into the black night, with the storm bursting upon them, and the destruction of the castle, which they witness in all its horror—are so vividly and dramatically described, and in verse of such undoubted power, that, in common justice to the author, we quote the entire passage:

‘The old man sat a little space,

Whilst pass’d across his lion face

A quivering spasm of sharp pain.

Then to his feet he rose amain,

And laugh’d a frightful laugh aloud,

And cried: He lies, this lord of thine,

I have no child—my Geraldine,

Behold her there in her death-shroud!

Sir, was it well to come like this,

And mock an old man’s wretchedness?

I know not what thy wild words mean:

But in this hideous misery

I have no heart to answer thee—

Away, and say what thou hast seen

To thy false lord! —Low sobs between

His strangled words came thick and fast:

And like the stabbing of a knife

Was his mad stare! Then all the Past,

The blow that crush’d his stricken life,

Struck back upon his soul anew—

And wearily, with piteous moan,

He sank beside the altar-stone.

‘There was no more that man could do,

No more that we would urge or say [page 19]

Where words must bootless be and vain.

So with sad heart we turn’d away

To seek our homeward path again.

But as beside the bier we pass’d

And on the bride-deck’d dead a last

Sad lingering look of pity cast,

The madness of a ghastly sight

Our souls assail’d. O sorrow and sin!

The lilies in her hands and hair

No whiter than her white throat were,

But in that throat’s translucent white

Two red spots burn’d, like a serpent’s bite

Where deep the fangs have fasten’d in!

And through the strokes of the passing-bell

There came the wail of a far-off cry,

Whispering low as it wander’d by—

A lover’s kiss—and the grave, instead.

If lover and serpent but one should be,

Beware the tryst by the linden tree—

Fool’s-heart, farewell!

‘With hurrying steps and reeling brain

We reached our tether’d steeds again,

And swiftly mounting urged our flight

Across the blackness of the night,

Whilst, all around, the rising sea

Swept o’er the land unceasingly

Before the storm-blast’s gathering sway.

The bellowing thunder roll’d alway:

And in the lightening’s livid sheen

A moment’s space the wildering scene

Stood out in strange and spectral hue, [page 20]

Till dropp’d the night’s dark pall anew.

We rode and rode, but as we pass’d

Beyond the flooded land, at last,

And gain’d the sheltering hills—we turn’d,

And Tryermaine’s tall towers discern’d

Pale in the lightning’s passing gleam:

And, all beyond, the broad balck sea

Swung dark and desolate! The scream

Of storm-blown sea-birds, * savagely,

Across the darkness drifted by:

And in the lurid quivering flame

(As ever anew the lightning came

In blinding glare o’er sea and sky)

A world of waters foam’d and flash’d

Along the shore—and rearing high,

Roll’d in upon the land, and dash’d

In thunder through the castle walls!

The lights a moment redly shone,

A moment more, and all were gone:

And from the distance, frantic calls

Of agony, and one long wail

Rose on the night, and died away—

Dear Lady ’tis a gruesome tale,

But little more remains to say.

We tarried till the break of day,

And when the dawn came, nought was there

But the flood-swept land and the swaying sea,

* We presume, the sea-eagles. We have heard their wild scream, more than once, on the storm-beaten coasts of Northern Scotland, and can well realise the author’s vivid lines:

‘And all beyond, the broad black sea

Swung dark and desolate!’ – THE REVIEWER. [page 21]

And the white gulls sailing and circling where

Tryermaine’s halls were wont to be!

We need hardly carry on our analysis of the story to the end of the poem. Enough, we think, has been shown to prove our author’s right to claim a fair position among, at least, the less ambitious singers of the day. In the volume before us there are many other equally striking passages that might be selected to show his metrical facility and his gift of livid word-painting, especially in his descriptions of natural scenery. The following weird picture of a solitary grave beside the loneliness of a great sea, is taken from his ‘Drama of Two Lives,’ an emotional story of modern incident: —

‘A sunken cross—the sea—the shore—

A levell’d sand-heap—nothing more

To tell the lonely sleeper’s tale—

A grave beside a storm-blown sea,

And on the land, nor leaf, nor tree,

And on the sea no gleam of sail

Or glint of wild bird’s restless wing,

Or sight or sign of living thing—

A scene that doth the soul oppress

With its wide utter loneliness.’

Here is also a final extract from another poem in the book—a twilight picture of a Canadian lake-scene, [page 22] showing in very musical verse, the same power of condensed description: —

‘The dead trees stand around—gaunt, bleach’d, and bare—

Like skeletons of strange weird things that were—

The black oozer trailing at their tangled roots:

Far-off, a solitary owlet hoots,

And all beyond the great grey waters lie

Pale in the gleam of stars. The night’s faint sigh

Floats o’er the pine-plumed islets, looking now

Like phantom ships that come with silent prow

And shadowy sails from some forgotten shore.’

On closing this review we may express the hope that Mr. Chapman will give us in good time some further opportunities of appreciating the lyrical power that he undoubtedly possesses.

L.

May, 1889. [page 23]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.