The Ryerson Canadian History Readers

Lorne Pierce, Editor

“Pupils who depend upon the authorized text alone for their information learn little or nothing about Champlain’s life except the days he spent in Canada. They know nothing about his fighting days with Henry of Navarre; that he travelled widely in Spanish America; that he wrote interesting books about his travels; that he was the first man to suggest the possibilities of a Panama Canal. All this and a very interesting account of all he did for his beloved colony, his toilsome wanderings through the primeval forest, his zeal in spreading a knowledge of Christianity among the cruel and ignorant savages, will be found in this very interesting little booklet on an early Canadian hero—Champlain.”—Manitoba Teacher.

What is true of Samuel de Champlain, by Adrian MacDonald, in the RYERSON CANADIAN HISTORY READERS, is equally true of the other gallant figures which form the theme of this series of short biographies of the great heroes of Canadian history. Against the background of Canada in the making stand out the romantic personalities of her makers—explorers, warriors, missionaries, colonists.

“A large number of these popular little books have made their appearance. . . . They make absorbing reading for any one wishing to get in Canadian history.”—Toronto Globe.

Printed on excellent paper, with clear type, from 16 to 32 pages, illustrated by C. W. Jefferys, R.C.A., an artist into whose exquisite little line drawings has gone a whole lifetime of historical research, vivid in style, intelligent recognition ofevery teacher, librarian, and student in Canada. Not only do the Ryerson Canadian History Readers provide the first complete history of Canada from East to West, based on the romance of personality, but they providealso the first complete pictorial history of the Dominion.

*Those marked with an asterisk are already published and available.

1. STORIES OF PATHFINDERS

*Pathfinders to America—S. P. Chester *Jacques Cartier—J. C. Sutherland *Henry Hudson—Lawrence J. Burpee *La Salle—Margaret Lawrence *Daniel du Lhut—Blodwen Davies *Père Marquette—Agnes Laut *Pierre Radisson—Lawrence J. Burpee *Alexander Henry and Peter Pond—Lawrence J. Burpee *John Jewett—Eleanor Hammond Broadus *Cadillac—Agnes C. Laut

2. STORIES OF PATHFINDERS

*La Vérendrye—G. J. Reeve *Anthony Hendry and Matthew Cocking—Lawrence J. Burpee *Captain Cook—Mabel Burkholder *Samuel Hearne—Lloyd Roberts Captain George Vancouver—F. W. Howay *Sir Alexander Mackenzie—Adrian MacDonald John Tanner—Agnes C. Laut *David Thompson—A. S. Morton *Sir John Franklin—Morden H. Long *Simon Fraser—V. L. Denton

3. STORIES OF SETTLEMENT

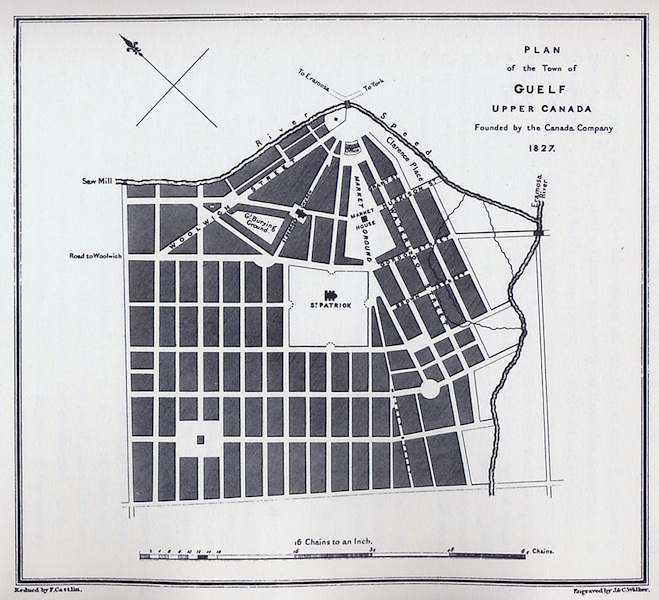

*Samuel de Champlain—Adrian MacDonald *Hébert: The First Canadian Farmer—Julia Jarvis *Frontenac—Helen E. Williams *Talon—Helen E. Williams *Old Fort Prince of Wales—M. H. T. Alexander *Colonel Thomas Talbot—Fred Landon The Acadians—V. P. Seary *Lord Selkirk—William Martin The United Empire Loyalists—W. S. Wallace The Canada Company—J. E. Wetherell *Prairie Place Names—Edna Baker

(This List continued on inside back cover)

[inside front cover]

PIERRE ESPRIT RADISSON

One of the fascinating things about history is the way that we often come upon forgotten facts through the most surprising sources. In this case we have to count and eccentric English writer, Samuel Pepys, whose diary of social doings in the seventeenth century is now deservedly famous, as one of the means by which we come to read in his own words the story of the earliest explorer of the Great North West—Pierre Esprit Radisson.

It is a story so strange and thrilling, so composed of what seems to us to-day unreal and barbaric adventure, that it is hard to realize that it all happened less than three centuries ago. It reads like a sort of savage fairy tale. One young Frenchman, armed chiefly with courage, high spirits and love of adventure, made his way west and north across an unknown wilderness of forests, plains and mountains, assisted by or fighting against untamed Indian tribes, sometimes with a small French escort, sometimes single handed, because he wished to open the doors [page 1] of a great secret—that which lay beyond. Often, as we shall see, he was repulsed and defeated, often he was detained for the moment in his quest, but always he returned. In the end, through his explorations, came the founding of what is known in history as “The Company of Adventures of England trading into Hudson Bay,” or “The Hudson’s Bay Company,” and the legal claim of the British Crown to immense territories, west, north-west and south-west of Hudson Bay, which are now the Provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta and the districts farther north and west.

Always, as Radisson travelled, he wrote down his notes. They were scrawled on scraps of paper or birch bark as he journeyed by canoe or broncho, or rested in some hastily rigged tepee after a strenuous day. He had no calendar, probably he had no time-piece, and many of his notes were lost. Years later, partly from memory, he re-wrote the notes in a journal of his amazing voyages. While he was living in London they came into the hands of the celebrated Mr. Pepys, whose executors, after Pepys’ [page 2] [page 3, includes illustration: RADISSON VISITING A WINTER CAMP OF INDIANS] death, sold most of the priceless writings as waste paper. Fortunately a great English collector, named Rawlinson, heard of it, and hastened to recover what treasures he could. Among other papers those of Radisson were given to the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Here they were rediscovered about 1885, and the strange thing is that these, among the most valuable of all papers relating to Canada, were unknown for two centuries, and first published in a limited edition of only 250 copies by the Prince Society of Boston.

Pierre Esprit Radisson was born, in Paris, of a family originally from St. Malo. His people came to New France when he was sixteen and settled at Three Rivers, even then an important fur-trading post of about two hundred French. It is situated at the three mouths of the St. Maurice River with lovely vistas of the blue St. Lawrence. Far behind the fort there stretched at that time limitless forests—the world of Indian tribes, at war among themselves and often against the French.

One morning, in the spring of 1652, three [page 4] boys evaded the sentry of the fort to go duck-shooting on near-by Lake St. Peter. It was easy to slip by for a raid of the Iroquois, always deadly enemies, had sent hundreds of terrified settlers to huddle behind the palisades. A mile from the fort they were warned by a herdsman not to go into the forest near the foothills. Pierre’s companions decided to return, but he laughed them to scorn and went on alone. After pursuing his way, and shooting for miles farther, he began to retrace his steps. But when he came near to the spot where he had parted from his comrades he stumbled over their mutilated bodies. He knew then that he was in great danger, and rammed a bullet into his gun. A mob of howling Indians sprang up from cover toward him, whereupon he fired at them with decision, and this saved his life, for the ideal of manhood among all Indian tribes is personal courage. Radisson had actually run into the ambush of the raiding Iroquois. They disarmed the boy without hurting him, and although they took him captive to their villages, in the present New York State, he was treated with kindness, [page 5] and taught how to use a paddle and throw the spear.

His spirit of laughter and daring made the months of his captivity among the Mohawk tribe a sort of initiation for all his dramatic future life. Something in Radisson endeared him to those who might have ended his life at any moment had they so chosen. Indeed, he was adopted by an Iroquois Chief and his Huron wife who had lost one of their own sons. They gave him the name Orimha, which means a stone, and, to honour his entrance to the tribe, a great feast was held. Slaves brought into the fire-lit lodge such delicacies as beavers’ tails, bears’ paws, and moose noses. He attended the feast decked as was befitting the son of so mighty a Chief. But Pierre was only waiting his chance to escape, and in the interval he was wise enough to master not only the Mohawk tongue but also scraps of Algonquin and Huron from captives among the Iroquois, and also a great store of woodlore and sign language which was later on to prove invaluable to him.

In escaping he had some incredible [page 6] adventures. That of August, 1652, for instance, when he set out with three Indians to hunt and make ready for winter raids, and was beguiled by an Algonquin captive to join in killing his escort and to escape to Three Rivers. But he was himself recaptured, and joined the death chant of other prisoners as their canoes floated down the Richelieu:

If I die I die valiant,

I go without fear

To that land where brave men

Have gone long before me—

If I die I die valiant.

Pierre was not allowed to escape without the punishment of torture, but his foster-parents managed to save his life, and the next spring he was off again with his tribe on war raids. This time he brought back a captive squaw and presented her to his foster-mother as a slave.

The Iroquois then made a bloodless raid on the Dutch settlement of Fort Orange, which stood on the site of what is now Albany. They looted cellars and pantries, but the Dutch bore it patiently because they [page 7] wanted their pelts in barter. Pierre accompanied them, disguised as a Mohawk, and after nearly two years saw white men again. Meeting them stirred afresh his desire for freedom and his own people, so one morning he left the lodge taking only his hatchet, as if he were going to cut wood, and as soon as he was out of sight plunged into the forest toward Fort Orange. The Mohawks followed him hot-foot, but he found a hiding-place in a settler’s cabin, and an escaped Jesuit, Pére Poncet, and a Dutch merchant from the fort, gave him money to take passage down the Hudson to New York, where he managed to get a ship to Amsterdam, and so reached Paris once more in January, 1654.

There Radisson found that all his early friends had disappeared. We shall probably never know the history of these three months. He returned to Three Rivers the next May, just two years from the time of his capture by the Iroquois. He was welcomed as one from the dead and reunited to his family—his father and mother, two sisters, an uncle and aunt and their daughter. The Iroquois and the French were at peace [page 8] for the moment, and the Jesuit priests had begun a mission among their former enemies. Radisson’s sister, Marguerite, had married Médard Chouart Groseillers a fur trader, who had been in his youth a lay helper in the Huron Jesuit missions. This new tie drew Radisson to mission work, and when three years later an Iroquois escort arrived to conduct a hundred Hurons to Onondaga, in the present New York State, for adoption into their Confederacy, Pierre, who knew their language, volunteered to go as a donné, or lay helper. He was, of course, on adventure bent, but he little realized how daring an adventure this was to be, or that his knowledge of the Mohawk tribe and of Indian superstition, and also his unfailing theatric sense, was shortly to save all their lives. For the Iroquois, always at heart enemies of the French, were up to their old tricks. The Jesuits had been encouraged and the garrison lured only in order to obtain their firearms. Hymns were sung within the palisades, but war songs were shouted outside. Finally Radisson realized that they had determined to massacre [page 9] all the mission and garrison except ten men, whom they planned to hold for the safe return of twelve of their warriors who were detained as hostages of good conduct at Quebec. In fact, the enemy was only waiting until the ice broke up in the spring.

Now, among the Mohawks encamped before the gates was Radisson’s Indian father, still a great Chief in his tribe. Through him Pierre knew for certain that doom was awaiting them all. But he also knew every fetish and superstition of the tribe to which he had belonged for so long. He knew their faith in dreams, their love of food, their fear of its waste. And so he had a dream—the dream of a great festival to be given by the French to his former friends. It was to be the feast of Eat-it-all or festins à tout manger. The very word “festival” gave it a religious character as well. He informed his foster-father of the coming event. He sent couriers speeding through the woods with the news. To the Indians it was just a good chance to get inside the French fort. They said to themselves that after all the whites were a simple people, they were making [page 10] it very easy for the Indians. But they loved to feast and came in hungry hordes to enjoy it. They were kept waiting for two days, amused with games, songs, dances, and races without the walls of the fort. Inside everything was made ready for immediate departure. Then, in the outer court the feast began, and no guest dared refuse the food heaped in front of him. The French kept up a constant din with drums, trumpets and other instruments, and danced and sang and shouted to keep their enemies awake. Radisson was everywhere, calling “Cheer up! Cheer up! If you want to sleep you must keep awake! Let the drums beat and the trumpets blow! . . . Cheer up! . . . Cheer up!”

By this time the Indians were so overcome by excitement, loss of sleep and much food that they could keep awake no longer. It may be that the food was drugged. At any rate the moment for escape had come, and the French hastened to depart. They moved into the inner court and locked and bolted the main gate. It was through this gate the sentry rope passed with a bell at [page 11] the end. Radisson fastened to the rope the one poor last remaining unsacrificed pig, so that every time the Indians should pull the rope the movements of the pig would cause them to think the sentry was on duty. About the barracks they set up stuffed clothes of soldiers. The sally port was forced open and the big boats, secretly constructed during the winter, launched. It was a cold raw night with sleet falling, and so a fearful journey down the river and across the storm-driven waters of Lake Ontario, down the St. Lawrence, where they had to wait for ice jams to break, across ice portages and over the turbulent waters of the rapids. But all except three, whose boat was wrecked, arrived safely. They reached Quebec on April 23.

All this was but a preface to Radisson’s important career as explorer and fur trader. Now it began in earnest, for on his return to Three Rivers he found his brother-in-law, Groseillers, eager to set out for the region beyond the Great Lakes. No white man had yet penetrated farther than Lake Superior, and the unknown was a mighty [page 12] lure to most young Frenchmen in North America. Radisson’s spirit flamed at the thought. But if they were to be first they must hasten.

Late in June, one dark night, they departed with Algonquin guides. Many French and Algonquins had left before them, whom they overtook in Montreal. The large party moved on recklessly and, ignoring the advice of Radisson, allowed their shotguns to be heard and so were attacked by the Iroquois and a number killed. Alarmed at the beginning of the adventure, all the French turned back but Radisson and Groseillers. You will find that these two always went on alone if necessary. When they reached the barren lands farther north they were comparatively safe. For a thousand miles they had travelled against streams, carrying their boats across sixty portages, now they paddled with the current westward to Lake Nipissing. On reaching Lake Huron they went on with the Indians whose destination was Green Bay, on Lake Michigan, and here they reached the country where no white man had ever seen. [page 13]

But again the Iroquois.

This was especially disheartening as the two, by a great distribution of gifts, had barely succeeded in appeasing the Algonquins whose braves had been killed in battle. Then word came of the approaching hostile tribe. Radisson offered to lead an attacking force; they caught the enemy unprepared so that not one of them escaped. Their popularity with the Algonquins was then secure and they made a triumphal progress—a kind of savage translation of old Roman triumphs—through this new land, accompanied by feastings and songs of welcome.

But Radisson and Groseillers felt that they must press on. Guides were provided, and early in 1659 they reached “a mighty river, great, rushing, profound, and comparable with the St. Lawrence.”

They had arrived at what we know as the Upper Mississippi. But to them it was the river of promise—the river of dreams. For a century explorers had been searching for a way to China, a short cut to the old world. But here was the first path to the new, and [page 14] the new itself stretched in joy and wonder before them. Simply and beautifully this young man, Radisson, still in his early twenties, describes his great discovery.

The country was so pleasant, so beautiful, and so fruitful, that it grieved me to see that

the world could not discover such enticing countries to live in. This, I say, because the

Europeans fight for a rock in the sea against one another, or for a sterile land . . . where the

people by changement of air engender sickness and die . . . Contrariwise, these kingdoms

are so delicious and under so temperate a climate, plentiful of all things, and the earth

brings forth its fruit twice a year, that the people live long and lusty and wise in their way.

What a conquest this would be, of little or no cost? What pleasure could people have

instead of misery and poverty! Why should not men reap of the love of God here? Surely

more is to be gained converting souls here than in differences of creed when wrongs are

committed under pretence [page 15] of religion! . . . It is true, I confess, . . . that access

here is difficult . . . but nothing is to be gained without labour and pains.

They learned of other great Indian tribes. The war-like Sioux farther West; the Crees, whose headquarters were on the shores of a large inland salt-water sea; the Assiniboines, midway between, who cooked their food in earthen pots; and the Mandans who had permanent villages like the Iroquois, on a great river that divided itself in two, called “the forked river” because it had two branches, “the one towards the west, the other towards the south . . . towards Mexico.”

What discoveries awaited them? Where should they go first? As their guides would not

go farther they “put themselves in hazard,” writes Radisson, by starting out alone. They

came to villages, the natives “all amazed to see us, and very civil. The farther we

journeyed the delightfuller the land became. I can say that in all my lifetime I had never

seen a finer country for all [page 16] that I have been in Italy. The people had very long

hair. They reaped twice a year. They war against the Sioux and the Crees. . . . It was very

hot there. . . . Being among the people they told us of men that had built great cabins and

had beards, and had knives like the French. . . . The people of these were large and well

built . . . their arrows were not of stone but of fish bones. Their dishes were made of wood.

They had great calumets of red and green stone, and a great store of tobacco . . . they had

a kind of drink that made them mad for a whole day. . . . We went towards the south and

came back by the north.”

It would seem, from the Journal, that the people of whom they heard from these tribes were the Spanish, and that, as they came back north, they must have seen Lake Superior. Somewhere near what is now Duluth they met tribes of Crees, who gave them important news of an overland route to the great northern inland sea which Henry Hudson had discovered fifty years before. [page 17]

These Crees had large supplies of pelts. Radisson and Groseillers were amazed at their quality, so, during the winter that followed, while the older man stayed in camp, Radisson started out toward the north-west with a band of a hundred and fifty Cree hunters. The great Bay of the North proved to be much farther away than they had been led to expect, and they only travelled two hundred miles. It was the hunting which chiefly interested Radisson, for he knew that the best beaver comes from cold shaded woodlands, and it seemed to him that this vast country between the great lakes and Hudson Bay must hold the wealth of the world in furs.

As it was, he had done well on his first expedition. So well, indeed, that he and his companion engaged five hundred Indians, from what was called the Up Country, to come down the Ottawa to the St. Lawrence with their brigades of canoes bearing furs in the spring of 1860.

At the Long Sault, where occurred an Iroquois raid in which the gallant Frenchman, Adam Dollard, and his companions had perished only eight days before, the northern Indians became panicky, but after a skirmish [page 18] the Iroquois were dispersed, and the explorers’ returning band came on to receive ovations at Montreal and Three Rivers, and at Quebec where there was a great demonstration.

In writing of it, Agnes C. Laut, an historian who has done much valuable work among

Radisson records, says: “Cannons from battery and bastion roared a welcome. Citizens

shouted themselves hoarse from the high terraced heights. Bells rang in all the churches,

and the Governor fêted them with gifts and feasts, for the cargo of furs saved New France

from bankruptcy. Furs were New France’s only crop and only revenue at this time.”

But at the root of the welcome, like a worm at heart of a rose, lay the bitter greed of those in power. It had become known that the two comrades had learned the secret of the overland route to Hudson Bay. Therefore, the Governor of Quebec decided to send out a party himself, and compel Radisson and Groseillers to act merely as guides. Of course he met with refusal. And then the fat was in the fire. The explorers were refused permission to extend their discoveries, [page 19] refused even a license to trade unless they gave up half the profits, dogged by spies, held back in every way, and finally forbidden to leave the boundaries of Three Rivers.

Presently a number of Indians arrived from the Up Country and asked for the explorers. They notified the Governor that they intended to go with the Indians. In reply he ordered them to await the return of a party he had sent up the Saguenay. The Indians hid in the rushes of Lake St. Peter, and the Frenchmen slipped away to freedom as Radisson had done years before at the same spot. Northward once more they sped, arriving at Lake Superior in October. In November they were coasting the south shore, and Radisson was told of the copper mines. The pictured rocks were shown him: “I gave them the name of St. Peter,” he said, “because that was my name and I was the first Christian to see it.” Near the north-west end of the Lake they built the first fort and trading post west of the Great Lakes. Its exact location is not known, but it was somewhere near the present Duluth—the beginning of white civilization in the vast north-west of this continent. [page 20]

The Indians there had never seen a white man, and Radisson was one who could enact great magic before their very eyes. They worshiped him as a king, and, when he journeyed west and north to the land of the Assiniboines, he and his companion were escorted by four hundred Cree braves.

We were Ceasars . . . there was no one to contradict us. We went away free from any

burden, while those poor miserables thought themselves happy to carry our equipage in the

hope of getting a brass ring or an awl or a needle. They admired our actions more than the

fools of Paris their king. . . . They made a great noise, calling us gods and devils. We

marched four days through the woods. The country was beautiful with clear parks. At last

we came within a league of the Cree cabins where we spent the night that we might enter

the encampment with pomp the next day. The nimblest and stoutest Indians ran ahead to

warn the people of our coming.

That winter there was terrible famine, but in the spring the Sioux tribes sent their warriors [page 21] to bring food in exchange for the hatchets and bells and beads that were housed in the log fort. Radisson travelled with them over what is now Manitoba, Minnesota and North Dakota. But his aim was always the Bay of the North, to which he presently set out with his friends, the Crees, and which his written record seems to make certain that he reached that spring. He speaks of the salt water and a great store of cows (caribou) and writes of “people who have a store of tourquoise.”

By the spring of 1663 the explorers were back in the region of the present Lake of the Woods, with hundreds of Indians. They had immense quantities of furs, and started for New France with three hundred and sixty canoes—but four hundred Crees turned back at the Sault.

Cannon welcomed them at Montreal. Quebec was amazed at the wealth of fur that they brought, but in the end their reward was chiefly fines and censure. Out of a large fortune they were left with comparatively little to cover their expenditures.

It was by this treatment that France not only lost claim to the vast territories of the [page 22] north-west, but also her explorers, for Groseillers now went to Paris to seek redress from the King. He failed to get it, so the two friends decided to leave New France for Nova Scotia which was in British territory. From there they tried to organize expeditions to Hudson Bay and, again disappointed, they took the advice of Sir Robert Carr, a British Commissioner at Boston, who urged them to renounce an ungrateful country and go to England. It seemed as though misfortune dogged them, for they arrived, in 1666, the year of the Great Plague. The Court had been driven to Oxford, and there another British Commissioner, Sir George Cartwright, laid before King Charles II the proposal of his companions to an expedition for furs to Hudson Bay. Their project met with favour, but the plague, and war with Holland, delayed them for two years. Then Prince Rupert came into the game. He was an adventurer at heart, and the fur trade, on such a large scale as that of the explorers, appealed very strongly to him. The Admiralty provided two vessels, with Radisson on board the Eagle and Groseillers the Nonsuch. Furious storms separated the [page 23] vessels off the coast of Ireland, and the Eagle was damaged and forced to return to London, but Groseillers succeeded in getting through to Hudson Bay.

Back in London Radisson, balked and apparently defeated in his schemes, began to put together from his scattered notes an account of his earlier voyages. We can imagine what comfort he must have had in writing at this time. He was courting a daughter of a distinguished Huguenot living in England, Sir John Kirke, and while waiting for news from Groseillers he and Prince Rupert worked to organize a great fur company. When the Nonsuch returned the next summer, heavily laden with a rich cargo, it was easy to arouse the enthusiasm of the English. So, in May, 1670, a royal charter was granted “The Company of Gentleman Adventurers trading into the Hudson Bay.” Prince Rupert was the first President.

The charter granted this Company an absolute monopoly of the greatest trade of North America. Yet, although his father-in-law was a partner, Radisson himself had only a salary of a hundred pounds a year and certain dividends. Moreover, he was a [page 24] Frenchman living in London. It was a curious situation. His own country had dishonoured him, but England, too, seemed to suspect his motives. Colbert, the great Minister of France, came to the rescue by offering the explorer, then nearly forty years of age, the payment of all his debts and a position in the navy if he would go back to France.

He left England to find that in France he was still the centre of court intrigue, for the King would not off end England by sending him with another expedition to Hudson Bay. Again he left for Quebec, where for long he tried in vain to get a hearing. Then suddenly the French had need of him, for they found that the English were beating them at the fur game and at last, in 1682, Radisson and Groseillers were off once more—this time in “two rickety sloops with seventeen men all told”—off to their hearts’ desire, the ever-beckoning Bay of the North.

Every kind of adventure happened now, icebergs, famine, mutiny, even a pirate ship, but finally they reached the Hayes River where they constructed a new fort named Bourbon. There they had a desperate encounter with a poaching vessel from Boston, and a Hudson’s Bay ship, both riding at [page 25] anchor in the inlet; one commanded by an old Hudson’s Bay captain, Gillam, and the poacher captained by Gillam’s son, Ben. This event alone makes one of the best sea-yarns in history, but there is only space to say that Radisson was able to double-cross Ben’s challenge to capture the poacher’s fort, and to take the English traders captive with him to Quebec in the spring.

Groseillers now returned to Three Rivers, disgusted with the whole tangle, and his son Jean took up the work of fur-trading.

Radisson was again summoned to France and secretly requested to re-enter the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company. But it took some intrigue to leave the French Government, who tried to force him into another expedition. He seemed to meet their wishes, but asked for leave to say good-bye to his family in London. He never returned to France, but joined the Company that he had helped to organize and left for Hudson Bay in The Happy Return in May, 1684. At his own Fort Bourbon he met Jean Groseiller, actively at war with the English traders thereabouts. He was naturally amazed at Radisson’s change of front, and it said much for the diplomacy of the explorer [page 26] that he was able to win pelts from Jean which were the property of the French, and to make a new peace treaty between the Indians and the English, which, by the way, is still effective.

Back in England, his success was acknowledged, and for five years thereafter, until he was fifty-five years of age, Radisson made annual voyages to Hudson Bay. Then war broke out with France, and French victories cut into the fur trade. Radisson’s salary was always small, and now his dividends began to fail. He was reduced to poverty, and a price was set on his head in France. What could he do? . . . What did he do? . . . History does not answer that question.

Among the “notes” of the Hudson’s Bay Company is one that is almost too pathetic to quote: “The Secretary is ordered to pay Mrs. Radisson, widow of Mr. Peter Esprit Radisson, who was formerly employed in the Company’s service, the sum of ten pounds, as charity, she being very ill and in very great want.”

No one knows where, or under what circumstances, the great Radisson died, or where he lies buried. He was not the sort [page 27] of man to whom the world hastens to pay homage—therefore he did not reap any of the usual rewards of fame. He was merely Pierre the clever one, the trickster, the pathfinder, the man of dreams and daring. Never a man with a fortune in his hand—never what people call successful.

One day, a year or two ago, on the observation car of a trans-continental train making its way across the prairie, we sat idly watching the large elevators and the small railway stations that flashed by at long intervals. One station bore the name RADISSON. In a moment we had passed it and were out of sight. To the casual traveller it meant nothing. He was absorbed only by the vista of blue horizon, the undulating prairieland, and the thought of near-by mountains. These seemed to be for the moment his actual possession.

Let us remember that they are forever the possession and also the monument of that one for whom the Great North West was first a dream, then a goal and finally a splendid attainment. [page 28]

(Continued from inside front cover)

4. STORIES OF HEROES

*Maisonneuve—Lorne Pierce *Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville—Norman McLeod Rogers *Mascarene—V. P. Seary *Marquis de Montcalm—J. C. Sutherland *General James Wolfe—J. C. Sutherland *Sir Isaac Brock—T. G. Marquis *Brant—T. G. Marquis *Tecumseh—Lloyd Roberts *The Royal Canadian Mounted Police—C. F. Hamilton *Nova Scotia Privateers—A. MacMechan

5. STORIES OF HEROINES

*Mère Marie de l’Incarnation—Blodwen Davies *Madame La Tour—Mabel Burkholder *Jeanne Mance—Katherine Hale *Marguerite Bourgeois—Frank Oliver Call *Madeleine de Verchères—E. T. Raymond *Barbara Heck—Blanche Hume *Mary Crowell—Archibald MacMechan *The Strickland Sisters—Blanche Hume *Laura Secord—Blanche Hume *Sisters of St. Boniface—Emily P. Weaver

6. FATHERS OF THE DOMINION

*Lord Dorchester—A. L. Burt *John Graves Simcoe—C. A. Girdler *Joseph Howe—D. C. Harvey *Sir John A. Macdonald—W. S. Wallace Sir George E. Cartier—D. C. Harvey George Brown—Chester Martin *Sir Leonard Tilley—T. G. Marquis *Thomas D’Arcy McGee—Isabel Skelton *Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt—J. I. Hutchinson *Sir Wilfrid Laurier—T. G. Marquis *Sir Charles Tupper—V. P. Seary

7. EMINENT CANADIANS

Bishop John Strachan—W. S. Wallace *Dr. John McLoughlin—A. S. Marquis *Samuel Cunard—Archibald MacMechan *Judge Haliburton—Lorne Pierce *James Doublas—W. N. Sage Edgerton Ryerson—C. B. Sissons *Fathers of Reform—Selwyn Griffin *Lord Strathcona—H. A. Kennedy *Hon. Alexander Mackenzie—T. G. Marquis *Sir Sandford Fleming—Lawrence J. Burpee

8. A BOOK OF BATTLES

*Siege of Quebec: French Régime *Sieges of Port Royal—M. Maxwell MacOdrum *Sieges of Quebec: British Régime *Louisburg—Grace McLeod Rogers *Chigneete—Will R. Bird *Pontiac and the Siege of Detroit—T. G. Marquis *Naval Warfare on the Great Lakes—T. G. Marquis Battlefields of 1813—T. G. Marquis *Battlefields of 1814—T. G. Marquis *The North-West Rebellion—H. A. Kennedy Canadians in the Great War—M. Maxwel MacOdrum

9. COMRADES OF THE CROSS

*Jean de Brébeuf—Isabel Skelton *Père Jogues—Isabel Skelton *Rev. James Evans—Lorne Pierce *Pioneer Missionaries in the Atlantic Provinces—Grace McLeod Rogers (64 pages, 20c.) *Bishop Bompas—“Janey Canuck” *Father Morice—Thomas O’Hagan

10. STORIES OF INDUSTRY

The Company of New France—Julia Jarvis *The Hudson’s Bay Company—Robert Watson The North-West Company—A. S. Morton The Story of Agriculture—Blodwen Davies The Search for Minerals—J. Lewis Milligan *The Building of the C.P.R.—H. A. Kennedy Canadian Fisheries—V. P. Seary Canadian Forests—Blodwen Davies Shipbuilding, Railways, Canals—H. A. Kennedy The Story of Hydro—Blodwen Davies

*Objective Tests—Lorne J. Henry and Alfred Holmes (based on ten selected readers, to test reading ability)

Price 10c. a copy; Postage 2c. extra

(Except Pioneer Missionairies in the Atlantic Provinces—20 cents)

THE RYERSON PRESS TORONTO

[inside back cover]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.