[5 blank pages]

CANADA THE SPELLBINDER

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

[unnumbered page, includes illustration: Salmon Fishing in the Far West (MORICETOWN, BRITISH COLUMBIA)]

CANADA

THE SPELLBINDER

BY

LILIAN WHITING

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR AND MONOTONE

LONDON & TORONTO

J. M. DENT & SONS LTD.

MCMXVII

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

TO

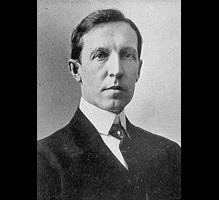

CHARLES MELVILLE HAYS

whose foresight and energy, whose courage and genius lifted Canada’s pioneer railway to a very high level of service and success; extended its operations from the Atlantic to the Pacific; opened thousands of miles of new scenic beauties and prepared a region which will ere long become a vital centre of population and strength to the British Empire; and whose passing to the larger and more significant activities of “the life more abundant” (by the tragic wreck of the s.s. Titanic, April 15, 1912) has left an unforgettable breach in the official family of the Grand Trunk System, an irreparable loss to his associates, to whom he was a beloved, constant, and forceful inspiration — this effort to interpret something of the romantic charm and richness of the resources of the Dominion is inscribed by

LILIAN WHITING.

“The shadow of his loss drew like eclipse

Darkening the world. We have lost him; he is gone;

We know him now; all narrow jealousies

Are silent; and we see him as he moved,

How modest, kindly, all-accomplished, wise,

With what sublime repression of himself.”

TENNYSON. [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

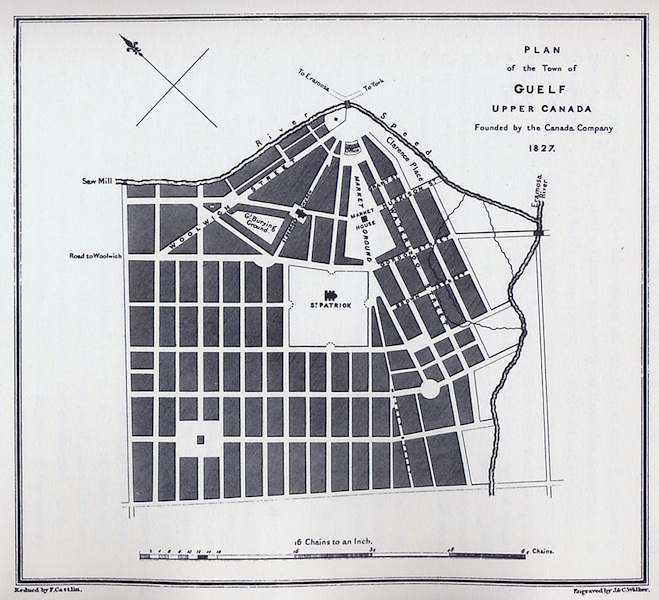

CONTENTS

| CHAP. |

PAGE |

| I. THE CREATIVE FORCES OFCANADA |

1 |

| II. QUEBEC AND THE PICTURESQUEMARITIME REGION |

46 |

| III. MONTREAL AND OTTAWA |

65 |

| IV. TORONTO THE BEAUTIFUL |

84 |

| V. THE CANADIAN SUMMERRESORTS |

100 |

| VI. COBALT AND THE SILVER MINES |

129 |

| VII. WINNIPEG AND EDMONTON |

141 |

| VIII. ON THE GRAND TRUNK PACIFIC |

159 |

| IX. PRINCE RUPERT AND ALASKA |

189 |

| X. PRINCE RUPERT TO VANCOUVER,VICTORIA, SEATTLE AND THEGOLDEN GATE |

217 |

| XI. CANADA IN THE PANAMA-PACIFIC EXPOSITION |

227 |

| XII. CANADIAN POETS AND POETRY |

245 |

| XIII. THE CALL OF THE CANADIANWEST |

289 |

| INDEX |

319 |

| [page vii] | |

| [blank page] |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| SALMON FISHING IN THE FAR WEST (MORICE-TOWN, BRITISH COLUMBIA) |

Coloured Frontispiece |

| FALLS ON GRAND FORKS RIVER |

facing page 4 |

| CAPE SANTÉ (QUEBEC), ST. LAWRENCE RIVER |

13 |

| SUNSET ON CANYON LAKE |

16

|

| A CANOEING PARTY, ONTARIO |

33

|

| DUFFERIN TERRACE, QUEBEC, FROM THE CITADEL |

52 |

| HARBOUR OF ST. JOHN, NEW BRUNSWICK |

61 |

| INTERIOR OF NOTRE DAME, MONTREAL |

68 |

| MONTREAL CITY |

77 |

| OTTAWA—SHOWING THE PARLIAMENT BUILDINGS AND CHÂTEAU LAURIER |

80 |

| THE BIGWIN INN, LAKE-OF-BAYS, ONTARIO |

97 |

| SIR ARTHUR AND LADY CONAN DOYLE AND PARTY |

116 |

| VIEW IN JASPER PARK |

125 |

| COBALT, ONTARIO |

128 |

| UNION STATION AND FORT GARRY HOTEL, WINNIPEG |

145 |

| MOUNT EDITH CAVELL AND CAVELL LAKE |

160 |

| CHARLES MELVILLE HAYS |

177 |

| HUDSON BAY MOUNTAIN AND LAKE KATHLYN, BULKLEY VALLEY |

180 |

| INDIAN TOTEM POLE, ALASKA |

189 |

| JUNCTION OF SKEENA AND BULKLEY RIVERS, BRITISH COLUMBIA |

196 |

| INDIANS SPEARING SALMON IN BULKLEY CAÑON |

205 |

| PRINCE RUPERT, BRITISH COLUMBIA |

212 |

| PURE BRED JERSEYS, WESTERN CANADA |

221 |

| MOUNT ROBSON, BRITISH COLUMBIA |

224 |

| LOOKING TOWARDS MOUNT MUNN FROM THE VALLEY OF FLOWERS |

241 |

| [page ix] | |

| BULKLEY GATE (150 FEET HIGH), BULKLEY RIVER |

244 |

| CANOEING ON THE FRASER RIVER |

253 |

| BREAKING CAMP |

272 |

| MOUNT ROBSON, AT A DISTANCE OF TEN MILES |

289 |

| FARMING IN SHELLBROOK DISTRICT, SASKATCHEWAN |

301 |

| THRESHING WHEAT, MANITOBA |

308 |

| AFTER THE BEAR HUNT—MOOSE RIVER FORKS |

317 |

| [page x] |

CANADA THE SPELLBINDER

CHAPTER I

THE CREATIVE FORCES OF CANADA

“All parts away for the progress of souls,

All religion, all solid things, arts, governments—all that was or is apparent upon this globe or

any globe, falls into niches and corners before the procession of souls along the grand roads

of the universe.

Of the progress of the souls of men and women along the grand roads of the universe, all other

progress is the needed emblem and sustenance.”

WALT WHITMAN (Song of the Open Road).

“The flowering of civilisation is the finished man, the man of sense, of grace, of accomplishment, of social power—the gentleman. What hinders that he be born here? The new times need a new man, the complemental man, whom plainly this country must furnish…. Of no use are the men who study to do exactly as was done before, who can never understand that to-day is a new day.”—EMERSON.

AGAINST a background of bewilderingly varied activities which projects from the earliest years of the sixteenth well into the twentieth century and reveals itself as a moving panorama of explorers, pioneers, adventurers, traders and missionaries, there stands out a line of remarkable personalities whose latter-day leadership has largely initiated as well as dominated the conditions of their time and the bequest of century to century. [unnumbered page] Among these were men, lofty of soul and tenacious of high purpose, who saw the potential Empire in a vast and infinitely varied region which seemed compact of unrelated resources. They were kindled by the growing achievements of the constructive genius that had already projected the wonderful steel highways carrying civilisation into the trackless wilderness. This constructive genius bridged the mighty rivers; created extensive waterways by means of canals connecting lakes and flowing steams; in still later years this genius commanded the cataracts and rapids to transform their ceaseless motion into motor power for traction, and lighting, and other service of industrial and economic value.

Each successive civilisation of the world, indeed, has shown an unbroken line of exceptional personalities in whom has been focussed the power of their epoch. They are the centres through which this power becomes manifest in applied purposes and special achievements. Civilisation itself is but the evolutionary representation of successive conditions of increasing enlightenment. With each succeeding age does man recognise more and more clearly his relation to the moral order of the universe. The guidance of unseen destiny leads him on, and in the records of no country is this working out of the invisible design more unmistakably shown than in those of the Dominion of Canada. This golden thread discloses itself to retrospective [page 2] scrutiny through a period of three centuries of time. “Man imagines and arranged his plans,” says Leblond de Brumath in his biography of Bishop Laval; “but above these arrangements hovers Providence whose foreseeing sets all in order for the accomplishment of His impenetrable design … Nor must man banish God from history, for then would everything become incomprehensible and inexplicable.”

The creative forces of an Empire include various and varying agencies. If to the courage and heroism of the original discoverers of the land too great recognition can hardly be given, yet to those who have made these discoveries of value by bringing the resources of a continent into useful relations with humanity recognition is not less due. John and Sebastian Cabot, Jacques Cartier, Champlain, Mackenzie, Fraser, and La Salle, were great pathfinders. But the very greatness of their achievements required such men as James McGill, Donald Smith (Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal), Sir George Etienne Cartier, the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, Sir Charles Tupper, and others, to stamp the early life of the pioneer with the seal of statesmanship and education. Here were vast areas of land; enchanting rivers, noble lakes, majestic mountains; untold wealth in minerals and in the boundless potentialities of agriculture; a marvellous [sic] country that is not only a land of promise, but a veritable Promised Land. Yet are [page 3] its possibilities like those of the ether of space, until it is rendered accessible to restless, struggling humanity by the indomitable power of great spirits, of wise and forcible leaders of progress who are perhaps the pioneers of the physical world in a degree similar to that of lofty beings in the realms unseen. It is such as they who create the conditions which render all these immeasurable resources of practical value to humanity. Such men as Sir William Cornelius Van Horne and Charles Melville Hays; men who have courage as well as vision; who see beyond all barriers; men who dare do that which weaker souls fear to attempt—such men are as truly among the creative forces of their country as are its original discoverers.

Little reference to these earliest years of Canadian history could be made, even in the mere outline which alone is possible in these pages, without a vivid recognition of episode and adventure so startling, so often brilliant and romantic, so often tragic in its heroic endurance and ultimate fatality as to illuminate the horizon of history with a flame not unlike the dazzling lights in Polar skies. There were miracle hours that condensed experiences as significant as those often diffused throughout an entire cycle of time. Mingled with these were the long, slow periods of patient labour. It is not with sudden leaps and bounds alone that life progresses, but by the steady, normal advance of persistent endeavour. Nor can demands for improved conditions [page 4] [unnumbered page, includes illustration: FALLS ON GRAND FORKS RIVER] [blank page] be always unmingled with some measure of judicious compromise. James Mill, referring to his experiences while in the London office, engaged with the affairs of India, says: “I learnt how to obtain the best I could when I could not obtain everything. Instead of being indignant or dispirited because I could not entirely have my own way, to be pleased and encouraged when I could have the smallest part of it; and when that could not be, to bear with complete equanimity the being over-ruled altogether.” Something of this philosophy the makers of Canada were compelled to accept. The incomers from France, the incomers from Great Britain, represented two distinct, even if not unfriendly nations. There were differences of race, of language, of creed. There were differing convictions as to institutions and laws. Until the Confederation the interests of the people were largely local rather than united. The unifying of a country of such enormous geographical extent and including such vital differences among its widely scattered inhabitants, must always prefigure itself as one of the signal feats in the statesmanship of the world.

The very magnitude of the resources and the infinite riches of Canada presented themselves in the guise of difficulties and obstacles to be conquered. Nature provided the vast systems of lakes and rivers; but these required vast schemes of engineering construction to render them of fullest service as continuous waterways. The broad rivers [page 5] must be bridged. Triumphs of construction have arisen, such as the Victoria Jubilee Bridge across the St. Lawrence at Montreal, a marvellous feat of engineering, and the splendid steel arch bridge over the Gorge of Niagara. Again, in the interests of transcontinental transit, the mountain ranges, whose peaks seem to pierce the sky, must be overcome. Unmapped tracts of almost impenetrable forests; wastes of rocks, and swamps, and the treacherous muskeg; or immense plains, still inhospitable to the destined tide of settlers, must all be subdued in the interests of the advancing civilisation and the development of a country bordering upon three oceans with an extent of coast-line exceeding that of any other country in the world. Then there were incalculable mining possibilities, precious metals, copper, iron, coal; there were unlimited resources of lumber, but the trees must be felled, and there must be railways or waterways to transport the timber. Canada offered water-power enough to turn the wheels of all the manufactories of Europe, but this power was useless until harnessed by the constructive genius of man. Another valuable asset was the pulpwood, the vastness of which suggested this country as the very centre of the pulp and paper manufacturing industry; but between the thousands of acres covered with white spruce trees, and the lakes and rivers contiguous ready to furnish the power, what marvels of mechanism must be duly constructed to bring [page 6] the pulpwood and the water-power into service of man. As an indication of the proportions to which this industry has already grown it may be cited that for the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1916, the Canadian pulp print papermakers shipped to the United States alone seven hundred and ninety-four and a half millions of pounds, an increase of one hundred and eighty millions over the amount shipped to the States in the preceding year.

Here, indeed, was a country rivalling any other in the world in the largess of nature, but whose every aspect was a challenge to the constructive enterprise of man. Nature, with unsurpassed lavishness, presented the raw material; it rested with man to stamp it with value. Thus the stimulus to industrial and commercial activities was second to none other in the history of nations.

These were the conditions that confronted, as well as rewarded, the early discoverers and pioneers. Did some prescience of all this potential wealth awaiting the centuries to come drift across the ocean spaces and touch minds sensitive to its impress?

“The Future works out great men’s purposes.”

John and Sebastian Cabot were impelled by a destiny as unrevealed to them as was that of Columbus. Each bore a magic mirror turned forward to reflect the promise of the future. In the hand of each was carried the lighted torch. It was passed [page 7] from each explorer to his successor. Cartier, who navigated the St. Lawrence to Quebec and then on to Hochelaga (the name given to the primitive Indian village on the site of which now stands the stately and splendid city of Montreal), carried the lighted torch still farther, and passed it on to Champlain who, three-quarters of a century later, came to found a trading-post on the island of Montreal—“La Place Royale” it was then called, the picturesque mountain that rises in the midst of the modern city of to-day having been named by Cartier “Mont Royale,” from which is derived the present Montreal. There followed La Salle, Marquette, Joliet, and others. Sieur de Maisonneuve consecrated the site of Montreal as the first act of his landing. It is little wonder that the visitor to this entrancing city to-day feels some unanalyzed and mystic touch pervading the air, something that must forever haunt and pervade his memories of stately, magnificent Montreal. No other city on the continent has this indefinable element of magic and of charm.

The seventeenth century was an almost unbroken period of bold and daring adventure and of missionary activities. All over the world, at this time, was there manifested the passion for exploration. It prevailed over the entire continent of Europe. It recorded its progress on the new continent of North America.

The discovery of Hudson Bay has been placed by [page 8] some statisticians as early as 1498, when it is surmised that Cabot may have reached it; but the absolute and authentic date still lingers somewhat in the region of conjecture and mystery. It was in 1607 that Henry Hudson is known to have first seen it as he sailed in search of the North Pole. Intrepid adventurer! He found, not the goal of his quest, but, instead, that “undiscovered country” we shall all one day see. “Hudson’s shallop went down in as utter silence and mystery as that which surrounds the watery graves of those old sea Vikings who rode out to meet death on the billow,” says a Canadian historian. Hudson Bay became a centre of intense interest to all the exploring navigators. Admiral Sir Thomas Button sailed in search of Hudson, or of some tidings of his fate. He returned without the knowledge he sought for, but with much information regarding all the western coast. Still later came Foxe and James. In 1631 Foxe discovered a fallen cross which he judged had been erected by his predecessor, the English Admiral, and he raised it and affixed an inscription and the date.

An organization that was pre-eminently one of the creative forces of Canada was that of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which traces its origin to a voyage of adventure made by two Frenchmen, Pierre Espirit de Radisson and Menart Chouart sieur Degroseillers, who were allured by rumours of the “inexhaustible harvest of furs” that awaited enterprising traders. Baffled for the time by [page 9] obstacles that seemed insurmountable, they returned to England to ask the assistance of King Charles II., and in 1666 was formed a company that included Prince Rupert (a cousin of the king), the Duke of Albermarle, the Earl of Craven, Sir George Carteret, and other noblemen and merchants, as the incorporators, to whom, in 1670, the king granted a charter to comprise “the whole trade of all the seas, bays, rivers, and sounds, in whatever latitude, … and territories of the coasts which are not now actually possessed by any of our subjects, or by the subjects of any other Christian prince or state.” In the following year two vessels were sent out within a short period and there sprang up a group of trading posts. Radisson remained for life in the service of the Company.

Against the living background of Canadian history in all its varied activities, no one contributing factor stands out with such prominence as that of this Hudson’s Bay Company which, for two and a half centuries, dominated the country and whose commercial importance played so large a part in her development. Let no one mistake the purpose of the Company, however, as one inspired by purely philanthropic or patriotic ardour. The dominant aim was by no means primarily that of the development of the new and almost unknown country. The servants of the Company were not braving the terrors and hardships of the wilderness on exclusively altruistic inspirations. On the contrary, it was [page 10] their policy to conceal the existence of the vast riches of the land and to represent it as inaccessible to any one beyond Indians and hunters. Even as late as the comparatively recent date of the decade of 1860-70, the pupils in Canadian schools were taught that all the Hudson Bay region was uninhabitable; that it was a desolate “No Man’s Land,” so to speak, covered with ice and snow. No effort to change this impression was made by those concerned with the administration of the Company, but, rather, they were more or less untiring in assisting to confirm it. They had their occult reasons for not being averse to the representation of the entire North-West as being quite valueless for the purposes of civilization. The impression, if not the conviction, was well authorised that the climate rendered the region quite impossible for habitation; and the region in which now lies the most wonderful wheat-growing belt of the world, and whose fertility under cultivation renders it capable of supporting a population as large as that of the entire United States at the present time (estimated at one hundred millions), was assumed to be a region only capable of sustaining wild animals, Indians, and the most hardy hunters and traders. Now it is traversed by three transcontinental railways which have opened an immense business of travel and traffic; and beside dozens of prosperous young towns and villages it contains Winnipeg with its quarter of a million people; Edmonton, Calgary, Saskatoon, [page 11] Regina; the important new terminal seaport of Prince Rupert, and the still older and more developed port of Vancouver; to say nothing of the scenic grandeur through all the Mount Robson locale, that has captured the enthusiasm of the world. The tradition of the rigours of climate has become so popularized that even as late as the summer of 1915 a New England tourist faring forth for a trip through the great North-West of Canada was urged to provide himself with furs and rugs enough to fit out an expedition to the Polar regions. As a matter of fact the only embarrassment encountered as to temperature was that of trying to discover sufficiently thin clothing for Winnipeg in the opening September days, where the sunshine poured down just then with a flood of radiance that fairly rivaled that of a summer in the Capital city of the United States. Yet, even in all this splendour of sunshine and discomfort of heat, that wonderful quality of the Canadian air was not wanting—a peculiar invigoration which one who has visited the Dominion misses for a long time after leaving the country. Edmonton repeated the same wonderful luxuriance with the same delicious coolness at night; and the journey on through the magnificent mountain scenery to Prince Rupert had the exquisite temperature of an Italian spring.

The Hudson’s Bay Company, however, was not organized on the basis of a bureau of publicity for [page 12][blank page] [unnumbered page, includes illustration: CAPE SANTÉ (QUEBEC), ST. LAWRENCE RIVER] the general benefit of the country and of posterity. Their aim was the gaining of wealth and it was one signally successful. Immense quantities of valuable furs were shipped homeward every year; the shares in the Company became more and more valuable as magnificent dividends were continually declared. They controlled a territory exceeding an area of two million square miles. It was peopled only by the Indians. Yet all through the seventeenth century run the records of that self-sacrificing and heroic band, the Jesuit missionaries, whose devotion to the Christian ideal led them on with a faith and fervor that consecrates their memory.

The ambition of the Company to extend their trading posts still farther and farther inland incited still more explorations into the unknown North-West. They builded better than they knew, for while their aim hardly went beyond that of increasing their own revenues, the results were inevitable factors in the development of the country. That this is true is not in any wise, as has already been said, to be regarded as in the nature of philanthropic or patriotic zeal. They regarded the country and its wealth in the light of a personal perquisite for their exploiting and financial benefit. They circulated the information that this was a “Great Lone Land,” as undesirable as it was inaccessible. From motives of self-interest, if not entirely those of humanity, the Company had treated the Indians with kindness and justice and had thus made the British flag something [page 13] to be held in respect by the tribes. Thus they had built up a strong reliance for themselves of friendliness on the part of the dusky natives. One of the eminent historians, George Bancroft, of Boston, U.S.A., calls attention to this attitude of the Hudson’s Bay Company, saying that both the officers and the servants of the corporation “were as much gentlemen by instinct in their treatment of the Indians as in their treatment of civilized men and women.” Thus, whenever they should wish to exclude, as enemies, those who came among them representing any other enterprise, they had strong supporters and coadjutors among the tribes. “No trespassers allowed” was practically their motto. Explorations, or the extension of trade, were alike vigilantly discouraged. “Notwithstanding the efforts put forth by the Company,” says one chronicle, “it was realised that unless the active co-operation of the Indians could be secured, white trespassers would inevitably make inroads into the trade of the Territory. Steps were therefore taken to unite the tribes against all whites not officially connected with the Company. The means adopted were worthy of the object desired, but could have been the outcome of an extraordinary disregard of the ordinary amenities of life. The Indians were told that these outsiders would rob and cheat them in the barter of their furs.” Still, the very prominence of the Company was its own enormous and inevitable advertisement, so to speak, of untold [page 14] resources connected with the mysterious regions, and both trade and further exploration were stimulated.

The first quarter of the eighteenth century had but just passed when (in 1727) Pierre Gaultier de Varennes (Sieur de la Verendrye), who was stationed on Lake Nipigon, became imbued with ardour regarding the great question of the day, the North-West Passage; and in 1731 he, with his three sons and an armed force of about fifty men, left Montreal for the West, reaching the shores of Lake Superior within two months, and pushing on—trading and exploring meanwhile—through the all but impenetrable wilderness until he sailed up the Red River, and in the autumn of 1738 established a fort near the site now occupied by the city of Winnipeg.

The great profits accruing to the Hudson’s Bay Company inspired rivalry, and in 1795 its keen competitor, the North-West Company, was formed under the leadership of Simon M‘Tavish, a Scottish Highlander, of “enormous energy and decision of character.” Still another company came into being, organised by two merchants of Montreal, John Gregory and Alexander Norman McLeod, which during its brief life was known as the X Y Company, to whose purposes was attracted a young Scotsman who was destined to be immortalized by his remarkable explorations and his discovery of the great river which perpetuates his name. This young man was Alexander Mackenzie, who came to Canada in 1779, and immediately entered the fur trade. He became [page 15] connected with the North-West Company and the X Y Company and left for the west to take charge of the Churchill River district. Later, owing to personal dissensions and conflicts of the Company with another of its agents, Mackenzie was commissioned to the Athabasca district, and it was there, apparently, that his project of exploration to the Arctic Ocean took possession of him. From the Indians he heard traditions of a mighty river like that of the Saskatchewan, and in June 1789 he had crossed Athabasca Lake and reached the Peace River which “displayed a succession of the most beautiful scenery,” as he recorded. He journeyed to Great Slave Lake after encountering immense difficulties—rapids, long portages, boiling caldrons, and treacherous eddies that threatened to engulf his barque; but at the end of the month he found himself on the river that now bears his name, and on the 12th of July he first sighted the Arctic Ocean. Then there intervened a visit to England before his second expedition in 1792. His memorable inscription on a rock, on the coast near Vancouver: “Alexander Mackenzie from Canada by land, 22 July, 1793,” tells its own story. It is not, however, with the long-familiar details of his expeditions that we are here concerned, but with the recognition of their result as one of the constructive factors of the Dominion. The story of these undertakings, of the adventurous journeys of the many explorers, inclusive of Hudson, La Verendrye, Mackenzie, [page 16] [unnumbered page, includes illustration: SUNSET ON CANYON LAKE] [blank page] Henry, Thompson, Fraser, Franklin, is a part of the story of Canada. To trace out the contributing causes and the influences investing each of these would be to throw a new illumination on the interrelations of the factors that have sprung into activity over a long series of years as involved in the evolution of a wonderful country whose great destiny impresses the civilised world.

The opening years of the nineteenth century were marked by a noble project that apparently ended in failure at the time and yet whose significance is not lost. In every worthy purpose, cosmopolitan, national, or individual in its scope, there is the germ of vitality, and dying in one form it is resurrected in another. Truly of such purposes may be said, in the sublime words of the apostle, that they are “sown in weakness, but raised in power.”

“The good, though only thought, has life and breath.”

Such a project was that of the Earl of Selkirk to assist numbers of his poorer countrymen by founding a colony for them in the Hudson Bay Territory, where they should find homes and engage in pleasant and profitable agricultural work. With Lord Selkirk it was not the dazzling opportunities of the fur trade that impelled his journey, when, in 1815, he with Lady Selkirk and their son and two daughters landed in Montreal, having already sent out three parties of his country people to the tract of land whose area was that of a hundred and ten [page 17] thousand square miles which he had purchased in the Red River Valley. His scheme for the betterment of these people included free transportation and temporary support for the settler until he could begin to make his own way, together with a free gift of the land. It was in 1810 that Lord Selkirk had matured his scheme and purchased the land; but on arriving with his family he found himself assailed with charges of conspiracy, condemned to the payment of fines that he contended were totally unjust, and confronted with a strange network of alleged misrepresentation and accusation. It would seem that his chief desire was that of generous and noble aid to his countrymen. His experience is not without its parallel pervading all history in the lives of men whose single-hearted aim has been to make the world a better place. Who shall penetrate the spiritual mystery in that he whose efforts are noble and unselfish not infrequently confronts the same results as might properly belong to him whose objects were quite the reverse of these? “And that all this should have come to you who had meant to lead a higher life than the common, and to find out better ways,” exclaims George Eliot’s Dorothea to Lydgate, in the great novel of Middlemarch; and the heroine adds: “There is no sorrow I have thought more about than that—to live what is great and try to reach it and then fail.”

Lord Selkirk took this experience greatly to heart. However much to be regretted is the failure of [page 18] sufficient courage and faith to enable one to stand strong, “and having done all, still to stand,” before a flagrant injustice or the pain of misconception, it is yet hardly to be wondered at that a sensitive spirit, conscious of its own integrity and unmeasured good-will, falters and faints before so unfortunate an experience. To the Scottish Earl it seems to have been more than he could endure. In 1818 he returned to Scotland, and soon after died, at the early age of forty-nine, in Pau, having gone to southern France in search of renewed health. The Red River settlement that he founded was in the neighbourhood of the present city of Winnipeg.

Historians differ, however, as to the motives of Lord Selkirk, some authorities taking a view quite opposite to the one cited here, and gathered, too, from trustworthy sources. The truth may lie somewhere between the two extremes. It is as unnecessary as it would be futile to endeavour to invest every leader of a movement with a golden halo like that of the mediæval saints of the Quattrocentisti. The world’s progress has always been carried forward by mixed forces and both ideas and institutions owe their vitality to complex aims and to a variety of conditions.

In the spring of 1821 the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Companies united. This marked an epoch in Canadian progress; and in 1838 occurred another event, unnoted as of any significance at the time, yet which proved to be the advent of one of the [page 19] greatest of the creative forces of Canada. “Any one watching keenly the stealthy convergence of human lots,” says George Eliot, “sees a slow preparation of effects from one life on another, which tells like a calculated irony on the indifference or the frozen stare with which we look at our unintroduced neighbour. Destiny stands by sarcastic with our dramatis personæ folded in her hand.” Surely the arrival at Montreal of a Scottish lad of seventeen years of age could hardly be held as bearing any direct relation to the future development and the cosmopolitan importance of Canada. Yet what a romance of history lies between the unnoticed landing of Donald A. Smith, in 1838, and the solemn grandeur of the scene in Westminster Abbey, in January of 1914, when representatives of the Crown, with the peers, the statesmen, the scholars, the social leaders of London; with a great concourse drawn from all ranks, met for the memorial service for Donald Alexander Smith, first Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal. “The memory of ten centuries of England’s illustrious dead haunted the scene.”

Donald Smith crossed the Atlantic in a small supply craft belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company and took up his duties as a clerk in one of the most unimportant branches of the service. He made the 1200 miles’ journey from Montreal to Labrador. He was stationed in a place where only once a year could any tidings reach him from the outside world. Was he lonely in this exile? He himself said that he [page 20] never knew what the feeling of loneliness was. He had books; he had thoughts. Such a psychologist as the late William James, who to his profound grasp of psychology and philosophy added the unmapped power of spiritual divination, would have found, in these long, solitary years of meditation and thought, the key and clue to the lad’s future greatness. In the infinite and unmeasured force generated by thought-vibrations lies power that may transcend a universe. “Mind with will is intelligent energy,” declares a recent scientific writer, who adds: “intelligent energy is enough to supply a cause for every known effect within the limits of the universe.”

Sir Oliver Lodge has recently said that life is simply “utilized and guided energy to produce results which otherwise would not have happened.” If the distinguished British scientist had been seeking a phrase to define the life of Donald Alexander Smith he could hardly have created one more felicitous. That the results that were called into activity for a period of over fifty years, of momentous importance to Canada, by the causes set up by the young Scotsman, matters that would never have happened but for him, is evident to all who study closely the modern history of the Dominion. Lord Strathcona’s biographer, Mr. Beckles Willson, introduces the reader to a long record of interesting details of the early years of Donald Smith, all of which contributed to the development and the [page 21] nurture of the marvelous qualities which rendered him one of the most determining of the forces that shaped the destiny of Canada. The brilliant John Jay Chapman, writing of the remarkable man who may be said to have initiated the abolition of slavery in the United States, remarks of his subject: “Garrison plunged through the icy atmosphere like a burning meteorite from another planet.” Not thus, however, did Donald Smith enter on his great career. Exiled in a far and frozen region, his service in Labrador lasted for thirteen years “with no companionship save a few employees and his own thoughts, learning the secrets of the Company, how to manage the Indians, and how to produce the best returns.[i] Thirty years had passed since his landing in Canada when, in 1868, on the death of Governor Simpson, of the Hudson’s Bay Company, whose office was in Montreal, Mr. Smith was appointed by the London office to succeed him. He was then in his forty-ninth year. Born on August 6, 1820, he died on January 21, 1914, in his ninety-fourth year. The forty-five years which preceded his passing from the physical realm were the years in which Canada entered on her great destiny, and of this momentous period Lord Strathcona might well have said, “All of which I saw and part of which I was.” His devotion and loyalty to the Empire was as intelligent and wise as it was ardent and powerful. The history [page 22] of Canada and his personal biography during those years might almost be interchangeable terms. The Hudson’s Bay Company, although organized and conducted on a financial basis, was the soul of loyalty to the Empire. The splendid courage, endurance and persistence that characterized its entire tenure entered into the very structure of the nation.

About the middle of the nineteenth century a man who has been termed “an uncrowned king” by some of the more enthusiastic, if not more discriminating of his followers; a man who was, at all events, an influential political leader and who especially espoused the cause of Upper Canada, opened a crusade for the acquisition on the part of the government of all the territorial rights of the Hudson’s Bay Company. This man was George Brown, the founder and at that time the editor of the Toronto Globe. He was a member of Parliament, and he was also one of the band of great editors in which the journalism of that period found its most potent expression. This order of editorial influence was represented in the United States by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune; Charles A. Dana of the New York Sun; and Samuel Bowles of the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, whose spirit and influence continue to manifest themselves in the high quality of that journal to-day. This dominant editorial influence still survives in the States, in the [page 23] personality of the brilliant and splendidly-endowed Colonel Henry Watterson, the proprietor and editor of the Louisville (Kentucky) Courier-Journal, and it was evident in the New York Evening Post, under the conduct of Horace White, whose death (in September, 1916) was a signal loss to the American press.

There is ample authority for the assertion that George Brown’s newspaper “had an influence on the populace such as no other hand in Canada.” It was under his administration of the Toronto Globe that this journal issued its first bugle call regarding the desirability that Canada should possess herself of all the wide sweep of the Hudson Bay territory of the west. This demand aroused from the Company a storm of emphatic declarations that the “Great Lone Land” was not worth the acquisition of the state; that its climate and its conditions rendered it forever useless to the interests of civilisation. Through nearly two decades had this agitation continued; but in 1869 the Government purchased the vast holdings of the Company at the price of three hundred thousand pounds and the further grant of one-twentieth of the fertile belt of land, and of forty-five thousand acres in addition adjoining various trading-posts. This transaction threw all the North-West into an excited state and Governor MacDougall was sent out to Fort Garry to still the commotion. Then came on the Rebellion incited and led by Louis Riel, the story of which is so familiar [page 24] to all readers of Canadian history. The conditions became disastrous and alarming, and Governor MacDougall was not permitted to move on to his appointed post. Under these circumstances Donald A. Smith decided to go immediately to the Red River country. He was not the man to hesitate when he heard the call of duty. He was at once invested with the authority of Commissioner by the Dominion Government, and the story of his success, and of the end of the first rebellion under Louis Riel, is too well known to require extended allusion. Soon after this Mr. Smith was elected to Parliament as the first representative from Manitoba. It was to his astute knowledge, his skill as a tactician, the great confidence that he inspired, and to his ability as a Parliamentarian that the successful settlement of the affairs between the Government and the Hudson’s Bay Company was primarily due. Meantime the problem of the consolidation of the Provinces became more evident as one that focused the interest of the time. The epoch-making solution of this problem came in 1867 when the Dominion was formed.

Canada was fortunate at this critical time in having a Premier of remarkable qualities, who was the man for the hour. John Alexander Macdonald (afterwards knighted and invested with the honour of a Grand Cross of the Bath) was a Scotsman by birth whose family removed to Canada in his early childhood. With the sturdy qualities of his race he [page 25] thus united the influences of Canadian environment and training, the family arriving in Canada in 1820, when the future Prime Minister was but five years of age. In his earliest youth, as a lad of fifteen, circumstances forced him into the world to earn his living. Life itself became his university. He developed in his first contact with the world that initiative, that instant perception of the situation and the facility to meet it, which so signally distinguished his statesmanship in after years. The family had landed at Quebec and journeyed to Kingston where they settled and lived until the death of the elder Macdonald in 1841, leaving the household in straitened circumstances. The Ontario of those days was very different from the smiling and prosperous Province of the present time. All Upper Canada (as it was then known) was covered with dense forests, and all means of transportation were primitive and slow. “Railways, of course, were unknown,” writes Sir Joseph Pope, the authorised biographer of Sir John Alexander Macdonald, “and macadamized roads, then looked upon as great luxuries, were few and far between. The climate, too, was more severe than, owing to the cultivation of the soil, it has since become.” In 1842, at the age of twenty-seven, Macdonald made his first visit to England, largely for the purpose of purchasing his law library. Quoting a letter written by him at this time to his mother, his biographer (Sir Joseph Pope) adds: [page 26]

“Forty-two years passed away and again John Alexander Macdonald stood within the portals of Windsor Castle; but under what different circumstances! No longer an unknown visitor, peeping with youthful curiosity through half-open doors; but as the First Minister of a mighty Dominion, he comes by the Queen’s command to dine at her table, and, in the presence of the Prime Minister and of one of the great nobles of England, who alone have been summoned as witnesses of the ceremony, to receive from the hand of his Sovereign that token and pledge of her regard which, as such, he greatly prized—the broad, red riband of the Bath.”

An omnivorous reader and endowed with a winning and impressive personality, Macdonald at once became a significant and an influential figure in Canadian life. Among the creative forces of his adopted and beloved country he holds a place never to be forgotten. He first took his seat in the Assembly of 1844; the new Parliament met in Montreal in the November of that year. Complex problems confronted the sessions of that period, in that Canada felt she had no potential voice in the administration of affairs. Every measure of the Assembly must secure the approval of the Legislative Council, the members of which were appointed for life by the governor-general, and added to this the measure must then receive the royal assent before it became operative. The conditions were also aggravated by the large majority of Canadians of French descent, sensitive and high-spirited, who rebelled against the invariable English rule of an English governor-general. These questions and other agitations made the political life on which [page 27] the young member entered one of peculiar intricacy. The Canada of that day was one of undeveloped resources and of internal dissensions. It consisted only of those territories which we know as the Provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island were in the same position politically as Newfoundland is in to-day, while the North-West provinces were a wilderness. With Macdonald’s rise to prominence in the political world the idea of confederation began to engage the attention of all those who had at heart the good of the country. The far-seeing leader of the conservative party began a campaign for the confederation of Quebec and Ontario with Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, believing that the best course was to bring about this preliminary union, leaving it open to extension if time and experience should prove it to be desirable. Owing to the closeness of party divisions, successive governments vainly attempted to carry on the work of the country. It was a critical period, and the manner in which a solution for the national troubles was found will remain one of the most striking episodes in the history of the times.

Sir John Carling was the means of bringing together the conflicting elements. He was a power in the affairs of Ontario and an enthusiastic supporter of Macdonald, while he also enjoyed the friendship of the Honourable George Brown, who was recognized as the Liberal leader of Upper [page 28] Canada, and who, for many years, had been the opponent of Macdonald. But the veiled and shrouded figure of Destiny hovered near. Did she bear a magic wand, concealed but potent? At all events she ordained that Brown and Carling should journey together from Toronto to Quebec on their way to attend a meeting of the Legislative Council. In their discussion of public affairs George Brown remarked: “Macdonald has the chance of his life to do great things for his country and these can only be done by carrying confederation.” To this Sir John rejoined: “But you would be the first to oppose him.” To Carling’s surprise Brown replied: “No, I should uphold him as I feel that confederation is the only thing for the country.” What a significant moment was this in the history of the future Dominion! Forces, determining but unseen, were in the air. The finely-balanced mind of Sir John Carling instantly grasped the importance of this psychological moment. “Would you mind saying to John A. Macdonald what you have just told me?” eagerly asked Sir John. “Certainly not,” replied George Brown, and his companion lost no time in bringing the two leaders together. The result is well known to all; the coalition ministry was framed and carried to a successful conclusion the great task with which it had been entrusted.

From that time until his death on June 6, 1891, the energy, the genius, the influence of John Alexander Macdonald were among the most potent of [page 29] the creative forces of Canada, and for the proud position that the Dominion holds to-day she is largely indebted to this great leader. One of the most important of his powers for national service lay in his ability to co-operate with strong men. When the movement for confederation was initiated the situation was extremely critical, and it was to the personal influence of the eminent French-Canadian, George Etienne Cartier (who was born in St. Antoine, Quebec, in 1814 and who died in 1873), that the support of a reluctant Province was won for the unification of Canada. Cartier was educated at the Seminary of St. Sulpice, Montreal; he was called to the bar, and as a followed of Papineau he fought against the Crown in 1837, and for some time after sought refuge in the United States. On the restoration of peace he returned to Canada and resumed his practice of law, attaining a high position, and subsequently he became the attorney for the Grand Trunk Railway. He was elected to Parliament in 1848 as the recognized leader of the French-Canadians and when, in November of 1857, John Alexander Macdonald succeeded Colonel Taché as Premier of the Province of Canada, Cartier was invited to a place in his cabinet. Later he was created a baronet of the British Empire. From 1858 to 1862 the Cartier-Macdonald ministry held its onward course, though steering its way through quicksands and tumult.

To Sir George Etienne Cartier is ascribed valuable [page 30] aid in the construction of the Grand Trunk Railway and the Victoria Bridge, important influence in the promotion of education, and signal service in bettering the laws of Canada. When, in 1885, a statue to his honour was unveiled in Ottawa, Sir John Macdonald in his address said of him: “He served his country faithfully and well…. I believe no public man has retained, during the whole of his life, in so eminent a degree, the respect of both the parties into which this great country is divided…. If he had done nothing else but give to Quebec the most perfect code of law that exists in the entire world, that was enough to make him immortal….” To Lord Lisgar the Premier wrote of Cartier: “We have acted together since 1854 and never had a serious difference. He was as bold as a lion, and but for him confederation could not have been carried.”

Another of the strong forces in constructive statesmanship was Sir Charles Tupper, who, almost unaided, engaged in the great struggle to overcome the opposition of Nova Scotia, his own Province, to the scheme of confederation. In this famous group of colleagues, Sir John Alexander Macdonald, Sir George Etienne Cartier, Sir Charles Tupper, and the Honourable George Brown, conspicuous ability and wonderful directive power were united with an optimistic courage, a depth of conviction in the success of important measures for the country, that rendered them practically invincible among the creative forces of Canada. Nor could any mention [page 31] of this progress be complete that did not include the name of Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley, many years Minister of Finance, a worker for confederation, whose own distinction of character and tenacity of purpose determined the attitude taken by his Province of New Brunswick in her wavering and tardy decision, only crystallized into adherence by the patriotic zeal of Sir Leonard. “It is perhaps the highest of all tributes to the genius of Macdonald,” says George R. Parkin,[ii] “that he was able to draw to his support a group of men of the weight and worth of Cartier, Tupper, and Tilley, and retain through a long series of years their loyal devotion to him as a leader. Each in his own way a commanding personality, they were of one accord in following Macdonald with unswerving fidelity through all the vicissitudes of his fortune. Along with him they grasped and held tenaciously the idea of a great and United Canada forming an integral part of the Empire, and to that and devoted the work of their lives.”

An interesting and graphic picture is preserved, in the literature of the time, of the visit of Sir John Macdonald, in 1879, to Lord Beaconsfield at Hughenden. He was received as Canada’s most illustrious citizen and leading statesman. After dinner Lord Beaconsfield conducted his guest to the smoking-room at the top of the house which was hung with [page 32] [blank page] [unnumbered page, includes illustration: A CANOEING PARTY, ONTARIO] old portraits of former Premiers of England. The host and his Canadian guest exchanged fragments of personal reminiscences and experiences, and Lord Beaconsfield greatly interested Sir John by his brilliant description of some of the notable personalities whom, in former days, he had met at Lady Blessington’s, who had a matchless gift for drawing around her the celebrities of her time. In bidding Sir John good-night, at the end of a long and delightful evening, Lord Beaconsfield said: “You have greatly interested me both in yourself and in Canada. Come back next year and I will do anything you ask me.” The next year duly came, but Beaconsfield had passed away, and Gladstone was the Premier. It was during this visit that the classics were discussed somewhat at length between Beaconsfield and his guest, the Premier of England, dwelling in the most fascinating manner, upon the poets, philosophers, and orators of Greece and Rome.

For nearly fifty years the influence of Sir John Macdonald was a very pillar of the Dominion. He represented a united Canada that forms so important an integral part of the mighty British Empire. Lord Lorne said of him that he was “the most successful statesman of one of the most successful of the younger nations.”

On his death Canada paid him her highest honours. Queen Victoria, most gracious of Royal sovereigns, wrote a personal letter of condolence to Lady Macdonald, and caused her to be elevated to the peerage [page 33] with the title of Baroness Macdonald of Earnscliffe. An impressive memorial service for the dead Premier was held in Westminster Abbey, and later his busy was placed in St. Paul’s and unveiled by Lord Rosebery. Almost every large city in the Dominion is adorned with a statue of Sir John Macdonald.

One of the most important services to Canada, on the part of the Premier, had been his early recognition of the immeasurable possibilities of the North-West. As early as in 1871 he saw that the construction of a railway to the Pacific coast was a matter of absolutely essential to the Dominion for the development of this portion of the country. In April of that year, while Sir John Macdonald was absent in Washington (U.S.A.) attending the proceedings of the Joint High Commission, Sir George Cartier moved a resolution in Parliament for the construction of such a road. The resolution was supported by Sir Alexander Galt and was carried. Sir Hugh Allan and Donald Smith had long held commercial relations, and the extensive and accurate knowledge of all this region that Mr. Smith had acquired was of inestimable value to the project. Into this intricate problem attending the decision and the subsequent fulfillment of it in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (completed on November 7, 1885) entered a group of important and forceful men. The magnitude of the work offers material for many chapters of Canadian history. Among this group [page 34] of dominant personalities stands out that of William Cornelius Van Horne (afterwards knighted) and who was particularly well characterized by James Jerome Hill who said of him: “There was no one on the whole continent who would have served our purpose so well as Mr. Van Horne. He had brains, skill, experience, and energy, and was, besides, a born leader of men.” The completion of this great highway was another of the events that closely linked the life of Canada’s great Premier with the forces that were creating her destiny. The first through transcontinental train on this line left Montreal on June 26, 1886, for its journey of 2905 miles through what was then an almost trackless wilderness. On the completion of the road Queen Victoria had sent a telegram characterizing the achievement as one “of great importance to the British Empire.”

The Grand Trunk was, however, Canada’s pioneer railway and it was the first railway in the British Empire outside the United Kingdom. One of the leading factors in the varied group of the creative forces of Canada, it is one of the monumental illustrations of her claim to foresight and enterprise in thus early recognizing that the art of transportation goes before and points the way for advancing enlightenment. The transportation service is, as one of the eminent officials of this line has said, “the advance guard of education.” In 1914 the Grand Trunk System, led by the vision [page 35] and foresight of Charles Melville Hays, completed its transcontinental lines. President Hays had predicted that the Grand Trunk would be able to handle the harvest of 1915, and his prediction was realised. His forecast for the future included steamer lines from Prince Rupert to Liverpool, by way of the Panama Canal, and further extension of lines to Australia, Japan, China, and Alaska. In fact, the Canadian prevision of unmapped possibilities of commerce that would be afforded by means of the new canal that thus connected two oceans was far more alert and engaging than that of the United States.

Beside the great enterprises involved in the conquering of nature, there were others, not less important, that contribute to the building up of human life. The claim of industry and economics is not greater than the claim of intellectual development, of scholarship, of that knowledge and refinement that leads to the highest social culture of a nation.

When the Honourable James McGill of Montreal left at his death (in 1813) a large bequest to found the university that bears his name he added another to the galaxy of Canada’s benefactors and creators. Mr. McGill had amassed large wealth in the fur industry, and the college, after encountering some years of difficulty, entered in 1885 on an era of prosperity that has continually increased as the years have gone by. This era of prosperity was largely due to the securing as Principal a gifted and remarkable [page 36] young man, John William Dawson, who is now so widely known to the world of science and scholarship as Sir William Dawson. For thirty-eight years he served as Principal of McGill. He found it a struggling college with less than a hundred students. He left it with more than a thousand students and with from eighty to ninety professors and lecturers. Finding it with three faculties, he doubled that number, and as within fifteen years he recognized the necessity of higher education for women, there was opened (in 1883) the Donalda Department, generously endowed by Lord Strathcona, which has since developed into the Royal Victoria College. Lord Strathcona gave, first and last, many millions of dollars to McGill; Sir William Macdonald gave to the Engineering department one million, including with this the schools of physics and chemistry, and he also equipped the Macdonald College at Saint-Anne-de-Bellevue which is incorporated with McGill. Peter Redpath, a public-spirited merchant of Montreal, presented the museum that bears his name (now rich in collections) and he also gave the Library building which houses, for McGill, the largest library in Canada save that of Parliament. These liberal gifts of Mr. Redpath were still further increased by Mrs. Redpath’s generous contributions. The unsurpassed opportunities at McGill place her graduates on equality of scholarly prestige with those of Oxford and of the other great universities of the world. No [page 37] consideration of the creative forces of Canada could fail to include this inestimable contribution that makes for nobler life offered by McGill University.

To the intellectual development and liberal culture of the Dominion the universities of Toronto and of Laval render priceless aid. The former is noted somewhat at length in a subsequent chapter. Laval University, founded in Quebec in 1852, by the Quebec seminary, dates back, through that institution, to its founder, François de Laval-Montmorency, the first Bishop of Quebec, who landed in Canada in 1659, and founded the seminary in 1663. This great French-Canadian university, fairly enshrined in sacred tradition and archaic history, is an object of pilgrimage to all visitors in Quebec. To its vast resources of scholarship it adds the perpetuation of the name of one of the most remarkable prelates that the world has known. A son of the crusaders, a true successor of the apostles who shared the life of Jesus Christ, a man of boundless charity, of intrepid heroism, of a life so consecrated to the Divine Service that its passing from earth in the May of 1708 cannot efface the vividness of his image nor dim the brightness of the atmosphere which enshrines his memory, he was deeply concerned with the education of his people. Monseigneur Laval specified that he desired that his seminary should be “a perpetual school of virtue.” The Abbé de Saint-Vallier of France bequeathed to this Seminary in 1685 the sum of forty-two thousand francs, and [page 38] Bishop Laval himself left to its maintenance his entire estate. The museums, lecture halls, and the library of Laval University are open to visitors. It is rich in historic portraits and in many fine examples of French art. On the visit of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII.) to Canada in 1860, the heir to the British throne founded the Prince of Wales Prize, which has remained one of the features of the university.

In the equalization of educational opportunities to an unusual degree Canada is especially strong. While the fiftieth anniversary of the consolidation of the Dominion will not be celebrated until July 1, of 1917, and while as a nation she is not yet half a century old, her educational privileges are recognized as among the best in the world. Not a single province is without its fully equipped educational system. Free public schools, high schools, colleges, and universities abound. There are already twenty-one universities in Canada. The standard of instruction is very high; the schools of applied science, law, medicine, and technical instruction are among the best in the world. They offer all late modern appliances for chemical, metallurgical, and electrical equipment: civil, mining, and electrical engineering are offered with unsurpassed opportunities for practice and research. The Royal Military College at Kingston presents a complete course in Engineering and in all branches of military science. The Royal Naval College at Halifax offers [page 39] equally complete opportunities for naval training.

Not even the most fragmentary survey of the creative forces of the Dominion could fail to emphasize the notable and beneficient work of Archbishop Taché, who, born in Quebec in 1823, became identified with the Far West in 1845, where he remained, an heroic and impassioned figure, until his death, in 1894. The Archbishop’s mother was a daughter of Joliet, the explorer; the same intrepid spirit that led this pathfinder on through the wilderness characterised the great prelate in a remarkable degree. At the age of twenty-two he had been admitted to the priesthood; he received his training in Montreal and was, from the first, “stirred to the soul by missionary zeal”; he eagerly embraced the call to the hardships, the most insurmountable difficulties, of the pioneer missionary. He traversed the country for four hundred miles around from St. Boniface (across the river from Winnipeg) where he was stationed; his journeys were by canoe and dog sledges; he encountered physical hardships which seem incredible for human endurance. When the slender financial support of his mission threatened to fail he pleaded that just sufficient revenue be continued to provide bread and wine for the sacrament, saying that for himself he would “find food in fish of the lakes, and clothing from the skins of the wild animals.” In his later years he was made the Bishop of Manitoba, and he was present, a venerable and honoured figure, on the opening of the first Assembly [page 40] of that Province in 1870-71. Archbishop Taché was one of the nearer friends and associates of Lord Strathcona, also when the latter, as Donald A. Smith, was so long the dominating personality in the North-West. The life and work of this great Archbishop of the Catholic faith are forever bound up with the history and development of Manitoba. There are other notable Catholic prelates, a remarkable group: his Eminence Cardinal Tashereau, the first Canadian prelate to become a Prince of the church; Archbishops Bourget and Fabre of Montreal; Archbishops Lynch and Walsh of Toronto; Archbishop Cleary of Kingston; and Bishop Demers of Vancouver are all among the great religious leaders whose influence for the general advancement of the people, as well as for the progress of religion, has been wide and invaluable.

Bishop Strachan of Toronto, a priest of the Church of England, whose life fell between 1778-1867, was a strong force both in church and state. No servant of God within the entire Dominion has left a nobler record. When (in 1832) the scourge of Asiatic cholera swept over Canada, it was he who inspired courage, administered the sacraments to the dying, and sustained the survivors. His aid, both legislative and otherwise, to the cause of education, and his activity in promoting all progress in Ontario, are among the most precious records of that province. One passage from his personal counsel may well be held in memory: [page 41]

“Cultivate, then, my young friends, all those virtues which dignify the human character and mark in your behavior the respect you entertain for everything venerable and holy. It is this conduct that will raise you above the rivalship, the intrigues, and slanders by which you will be surrounded. They will exalt you above this little spot of earth, so full of malice, contention, disorder; and extend your views, with joy and expectation, to that better country.”

Nothing in all religious advancement is more impressive than the great work of the Methodist denomination in Canada. Their vital and fervent spirit has kindled the zeal of the people with the flame of the living coal on the altar. One of the remarkable contributions to the lofty order of creative forces was made by the Reverend Doctor Egerton Ryerson, the celebrated Methodist leader, and the organiser of the Public School System of Ontario. In 1841 Doctor Ryerson became Principal of Victoria College; in 1844 he was appointed Superintendent of Public Schools in Upper Canada, and he brought to bear upon educative work the enduring impress of his ideals. “By education I mean not the mere acquisition of certain arts,” he said, “but that instruction and discipline which qualify men for their appropriate duties in life, as Christians, as persons in business, and as members of the civil community.” Doctor Ryerson lived until the year 1882, and he thus was enabled to see much of the fruit of his wise and untiring endeavour.

Although the Right Honourable Sir Wilfrid Laurier is still, happily, dwelling among his countrymen [page 42] and lending to many notable occasions the rare distinction and the prestige of his presence, the gratifying fact that he is a factor in the life of the hour cannot constrain one to fail to express the recognition of Canada’s indebtedness to his splendid services during her more recent past. A native of Quebec (born in 1841) his unqualified devotion has been given to the Empire without regard to restriction of race or language. His political career as a member of the House opened before he was thirty years of age; six years later he was called to the Cabinet; and in June, 1896, at the age of fifty-five, he became the Premier of the Dominion. When the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated, one special feature was the invitation extended to all the Prime Ministers of the British Empire to honour it by their presence. Among these Ministers Sir Wilfrid was singled out for many special attentions. He was distinguished by being made a member of the Imperial Privy Council; he was appointed a Knight of the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George; he was invested with honorary degrees by both Oxford and Cambridge; he was made an honorary member of the Cobden Club which awarded to him a gold medal “in recognition of exceptional and distinguished services to the cause of international and free exchange.” Sir Wilfrid Laurier visited President Faure and the President of the French Republic named him as a Grand Officer of the Legion d’Honneur. [page 43] In 1902 Sir Wilfrid was invited to the Coronation of Edward VII. and his presence at this imposing ceremonial reflected distinction of the highest order on Canada by his brilliant and impressive addresses made on Imperial interests and affairs. England could not but realise that in the Parliament of the vast country over the sea there were orators who would add new luster to her national eloquence and splendid traditions.

Well, indeed, has Canada been called the country of the Twentieth Century. To no inconsiderable extend the appliances that introduce a new order of life have been either invented or first experimentally considered in the Dominion. Indeed, as if already under the spell of Destiny, these great modern miracles of communication—the railways, telegraphs, and telephones will be forever associated with the name of Canada; the country that cradled James Jerome Hill and Samuel Rogers Calloway; in which William Cornelius Van Horne and Charles Melville Hays gave the best years of their lives to building and improving transportation facilities; in which Alexander Graham Bell initiated his experiments and where he still makes his summer home; and in which Thomas Alva Edison worked as a telegraph operator on the pioneer railway, where he printed and issued The Grand Trunk Herald, the first newspaper ever printed on a railway train.

In the light of the eventful period that has passed since that momentous date of August, 1914, it would [page 44] seem to be a curiously prophetic glimpse that rose, like a mirage on the far horizon, before Sir Wilfrid Laurier when, in response to a toast at the banquet given on June 18th, 1897, by the Imperial Institute in London in honour of the Colonial premiers, he said:

“…England has proved at all times that she can fight her own battles; but if a day were ever to come when England was in danger, let the bugle sound, let the fires be lighted upon the hills, and in all parts of the Colonial possessions whatever we can do shall be done to help her. …. I have been asked if the sentiments of the French population of Canada were those of absolute loyalty towards the British Empire. Let me say … it was the privilege of the men of our generation to see the banners of France and of England entwined together victoriously on the banks of the Alma, on the heights of Inkermann, and on the walls of Sebastopol.”

Seventeen years had but passed—from 1897 to 1914—when again the banners of France and England were intertwined; and since that fateful midsummer’s day what treasure and sacrifice has not Canada poured out with a courage and unflinching heroism for which words furnish no adequate interpretation. The future of the Canadian Dominion is seen, in the words of the poet, as “along the grand roads of the universe.” Her citizens realise that “To-day is a new day” and the hand of Destiny is leading her on to exemplify to the world a new and a more glorious civilisation. [page 45]

CHAPTER II

QUEBEC AND THE PICTURESQUE MARITIME REGION

THE Maritime region of Canada embraces only, strictly speaking, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick; although Quebec is sometimes thought of as being included in this historic portion of the Dominion, because of its geographical situation. The city of Quebec has always been a favourite point of pilgrimage, and when Mr. Howells, in his early youth, enshrined it in a half-romantic narrative, as the scene of Their Wedding Journey, its attractions were heightened by his facile and charming pen. The old French city dates back to 1608, and its history, for more than a century and a half, is really the history of Canada as well. All the maritime provinces of Canada take a prominent place in poetic legend and lore as well as in historical associations. When, in 1845, the poet Longfellow wrote his tender and touching, though historically misleading poem, Evangeline, the poem focused the general attention on Acadia (the modern Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), and particular attention on the little village of Grand Pré, which,

“…distant, secluded still,”

lying in the fruitful valley, invited many excursions [page 46] of those who delight in pilgrimages to poetic shrines. For

“Plant a poet’s word but deep enough,”

and woodland or hill, mountain or shore, are thereby enchanted. The Maritime region, still vocal with the dreams and discoveries of adventurous spirits; where all pledge and prophecy still linger in the air; where impassioned endeavour, long-patient endurance, faith to break a pathway through to untrod regions with some Ulysses to inspire a faith that it is never too late to seek a newer world—how wonderful is the spell this province weaves around the wanderer!

The noble St. Lawrence is a river that fairly fulfils the purposes of a sea, with its kaleidoscopic shore lines, now bold and forbidding, now dreamy and undefined with their fleeting, ethereal beauty; and all the maritime land is pervaded by memories and associations of the brave Cabot who first sighted Nova Scotia on June 24, 1497, the date of the special festa of his native Italy—this festival of San Giovanni, when all Venice is on the Grand Canal in the fleets of Gondolas; all Florence illuminated at night, a resplendent spectacle from her surrounding hills and her background of purple amethyst mountains; and when Rome, at night, disports herself in a thousand ways upon the Campagna Mystica. It was a fitting date for Cabot, the Venetian, to discover the new land. Voices unheard by others had called to him; hands, from starry [page 47] spaces, beckoned and led him on. What was there in the air but

“Winged persuasions and veiled destinies,”

and all the past that came thronging to meet all the future? Cabot, Venetian born, English by adoption, was followed by several other intrepid explorers, and not to insist too much upon chronological order, what a group of wonderful names are associated with all the province of Quebec! Cartier, Champlain, Frontenac; Sir Humphrey Gilbert of the Elizabethan period, whose brave expedition was engulfed by winds and waves and went down in the great deep off Campobello.

“Alas, the land-wind failed, And ice-cold grew the night, And never more on sea or shore, Should Sir Humphrey see the light.”

But the high ideals these heroes brought did not go down nor become extinguished in the storm-tossed waters.

“Say not the struggle naught availeth!”

The struggle always avails, and leaves humanity better and farther on than the effort finds it. Then, too, came a band of holy women, the Ursuline nuns, and the sacred zeal of the novitiate lent its vital power. What is there not of spiritual nobility, of sublimest self-sacrifice, or thrilling ideals, of a truer life, associated with the early history of Canada? This is all a part of her spellbinding power; it has [page 48] left its significance on the air, its impress in wave and tree and flower; its exaltation in every heart.

Quebec city is now becoming an attractive winter haunt as well for those who love out-of-door sports in the snowy carnival and who find themselves so comfortably domiciled in the Château Frontenac. The esplanade of Dufferin Terrace commands delightful views across the St. Lawrence as far as the Isle d’Orleans. The Citadel, the Parliament Buildings, the Ursuline Convent, the Basilica, and the palace of the Cardinal; together with the libraries, Laval University, the drives to the old battle-grounds, and the excursion of twenty-one miles to the shrine of Saint Anne de Beaupré, provide the visitor with abundance of interest.

The Ursuline Convent covers seven acres of ground in almost the centre of the city of Quebec. It is the largest convent on the continent, and it dates back to the July of 1639, when Marie Guyart, and three other sisters of the Ursuline order, under the protection of the Archbishop of Toulouse, were led by Divine guidance to the new country of Canada and entered on their work. Marie Guyart, the foundress of the convent, was the daughter of a silk merchant of Tours, France, and her childhood is invested with legends similar to those that are associated with the name of Catherine of Sienna. She married one Joseph Martin, but at the age of twenty-three she was left a widow, and soon became a novitiate of the Ursulines, rising to be the [page 49] Mother Superior of her convent. At the age of forty, through the instrumentality of the Duchesse D’Aiguillion, a niece of Cardinal Richelieu, she came to “New France,” and as recently as the August of 1911 this remarkable woman was canonised by the Sacred College of Rome and named as a saint under the title of Marie de l’Incarnation. For thirty-three years she pursued an exalted life in the convent of her founding, and died at the age of seventy-two, in the May of 1672.

A much-sought shrine is that of Saint Anne de Beaupré, easy access to which is gained by the electric railway, and in the summer it is a pleasant local sail down the St. Lawrence. The legend runs that a group of Breton mariners, in the early years of the seventeenth century, found themselves almost engulfed in the river in the sudden violence of a storm, and that they called upon la bonne Saint Anne for deliverance; earnestly declaring that if she would save them they would erect to her a shrine at whatever point she should bring them to land, and that this shrine should be sanctuary forever. The good saint was merciful to their entreaties, and guided them safely to land. According to their promise they at once built a small wooden chapel, very near a spring whose waters are claimed to possess a miraculous power for healing. Since that remote time three larger churches on this site have successively replaced each other, the latest of which dates only to 1878. The primitive little chapel is [page 50] still preserved, even as at Assisi the Portiuncula of San Francisco is preserved near the magnificent church of Santa Maria degli Angeli.

That marvellous ministry of San Francisco (who is more familiarly known to us as Saint Francis of Assisi), which was initiated in the thirteenth century, love and sacrifice being the supreme ideals, is recalled to mind by many of the legendary incidents relating to Saint Anne de Beaupré. The mystic pilgrimage to Assisi, the “Seraphic City,” is to some extent paralleled by the latter-day pilgrimages to the shrine of Saint Anne. “Any line of truth that leads us above materialism,” said Archdeacon Wilberforce of Westminster Abbey, whose passing on to the life more abundant at the date of this writing is but the larger inflorescence of his beautiful and consecrated life—“any line of truth that forces us to think and to remember that we are enwrapped by the supernatural, is helpful and stimulating. A human life lived only in the seen and felt, with no sense of the invisible, is a fatally impoverished life; a poor, blind, wingless life.” Such is the deep, perpetual conviction of mankind. “The things that are seen are temporal; the things that are not seen are eternal.” The mystic union of the soul with God is the one underlying and all-determining truth of life.

“Oh, beauty of holiness! Of self-forgetfulness, of lowliness.”