The Story of

Armand Villiers

Being the

Crusts and Crumbs

for Christmas, 1916

By

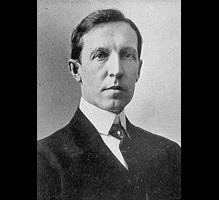

Albert Ernest Stafford Smythe

[unnumbered page]

[blank page]

THIS IS THE KIND OF STORY that writers of fiction like to have on Christmas Eve or Christmas night, but I have not the slightest authority for saying it happened on either the one or the other. It is the sort of story that naturally fits the Christmas season, and it must have happened in the winter time or there could not have been snow on the ground, and the snow gives it a Christmassy look, and one somehow thinks of the carols of Noel in connection with it. There is the same doubt about the place as there is about the time, but I am inclined to think it was somewhere in Belgium in one of those quaint and lovely old places which have been so ruthlessly desolated by the hosts of the Kaiser under the inspiration of his Kultur of the All-Highest. It may have been in Louvain, where first the brutality of the Germans became fully apparent; or it may have been in Ypres itself, under the shadow of that lovely hall which the German guns smashed to fragments out of spite and revenge because they could not break the indomitable ranks of Nonnebusch.[unnumbered page] And I think to the perceiving mind there is no greater condemnation needed for the doctrine of frightfulness as the Germans deliver it, wherein I differ from friends like Horace Traubel, who seem to think that all soldiers are alike and all nations that go to war are equally worthy of condemnation. Armand Villiers had known war and known it in its most ghastly shape, but this is not a war story. Those who wish to know what kind of Purgatorio Armand came through may read Zola’s “The Downfall,” and imagine him in the worst of it, wounded, maimed, broken. After the war and the Commune in 1871, Armand returned to his home near Paris to find that he was alone in the world, his family swept away by hunger and disease, nothing left to him but his violin, which had somehow escaped in the general catastrophe. It was an old family possession. His grandfather had been a noted violinist. His father had escaped the musical passion of his family, but tenderness for his father and reverence for the family tradition caused him to treasure the precious fiddle, and little Armand was encouraged to play upon it. But Armand had other interests as a youth, and he did not spend his soul on the violin at first. Music had not awakened [page 6] in him yet. His delight was in the world without.

IT WAS WHEN HE HEARD WILHELMJ that he recognized the heavenly gift. It was in the year before the war. The master was in his prime, David’s greatest pupil. Armand had heard great violinists before, but never one that touched the secret chord in his heart. As he listened to the first mellow golden vibrations that Wilhemj drew from the throbbing instrument a new world opened for him. He was about the same age as Wilhelmj himself, and there arose a great regret in his mind that he had not devoted himself, as he might have done, to this wonderful art. But there was no envy in him, for he was a true artist, and rejoiced in the glory of Wilhelmj’s triumph. It was little more than a year afterwards until Bismarck forged the telegram that set France and Prussia at war, but in that time Armand dedicated himself to his violin and endeavoured to recall to his fingers the supple responsiveness of his childhood. He had played as a little boy and had practised occasionally or there would have been little use in his attempting to discipline the stubborn muscles of thirty-five. As month after month [page 7] passed his assiduity gave him ever-growing control and mastery over the four elements of the magic quartette. Bit just as he began to hope for some success came the war, and in seven weeks he was a wreck in a hospital and minus his left arm. In after days he used to tell of those long months in which he slowly rallied from the shock of his wounds. He had time to think of his ideas of life, and what life was for and what he had to do with it. The doctors and nurses use to think he had lost the balance of mind, as it is called, which enables a man to occupy himself contentedly with the most commonplace affairs and be satisfied with the most conventional explanations and excuses for the perversity and injustice of things as they appear to be. When he told them of some of his experiences as he marched with his regiment in the early days of the war, overwhelmed with fatigue, numb with hunger, not knowing whether he slept or waked as he marched, they told him he was hallucinated, and that such experiences were quite common and of no importance. But certainly, he declared, he had seen some things that could not be put aside so, and he had heard celestial music, the most wonderful, the choicest, the melodies most rare, the harmonies [page 8] the most seraphic, so that the music of the spheres or of the heavenly choirs, whatever it might be, could not surpass it, or his appreciation rise any higher. It was the supreme delight, and he would go through the war once more but to enjoy the bliss of hearing those angelic strains again. The doctors only looked wise and muttered something about battle-delirium, and the nurses tapped their foreheads, and Armand learned to keep his peace, and when he gained a little strength he took his violin and set out to find work for the arm that was left to him.

SO IT WAS THAT HE FINALLY settled in the quaint old Belgian town and gradually became a figure in its streets, and was pointed out as the man mad about celestial music. He always insisted that he had once heard music ineffable, incomparable with anything to be elicited from earthly instruments, but he thought that from the vibrations of stringed instruments divinely played there might be produced something akin to those glorious measures. What we have here, he would say, is but the dull counterpart of what shines within us and above us. I have lost an arm, he would say, and gained a [page 9] whole body. What does it mean, otherwise, he would ask, when the blessed St. Paul says himself, “Il y a un corps animal et il y a un corps spirituel”? How do I know? Have I not an arm that you can see, and have I not an arm that you cannot see? And my invisible arm is my most precious. When I had fingers of flesh and blood I could make but indifferent music, and I was stupid in my runs and my stopping. But now, my faith, when I would play like Paganini, I can play like Paganini, but it is with invisible fingers on invisible strings. You see not that wonderful arm, and that subtle and dexterous left hand, he would say, but I feel them and I hear with my inner ear the music they make. Then he would lay his cheek lovingly, as it were, against an invisible violin, and draw an unseen bow over the strings that no one heard or saw but himself, and his face would light up with the rapture of the inaudible heavenly sounds. There were only a few sympathetic souls to whom he would speak of these things for he knew that the rest would regard him as a madman, and to be considered sane he must appear commonplace. Shall the earth have sorrow, he would say, and shall it not have joy? Have we not had war, and perhaps even [page 10] yet again, and worse than before? And shall there not be solace in the midst of the desolation and peace in the soul though the body perish? Do I not know, for have I not lost part of my body, and shall I fear to lose it all? Were I a lobster I would grow a new claw. Think you I shall not be able to grow a new body at my need? I have read; I have heard; and I know.

ARMAN WAS FIFTY WHEN he told the Cure, who came to talk to him once about his soul, that he was not troubled about his soul at all. Did you ever hear about Orpheus? he asked the Cure, and the Cure admitted that he had. Armand believed that Orpheus was a saviour of the world, and that he brought the divine gift of music. Did he not enchant the earth with his new song? And what is enchantment but the singing of the chanter? The old Greeks knew of Orpheus; but they did not preserve his wisdom. It belonged to the Keltic race and came down through thousands of years. His lyre had seven strings, but no one knew how it was made or how he played upon it. It might have been like the harp, but the harp did not sing as the strings should do in sustained cantabile, like the song of the morning [page 11] stars. He knew about the rebek and he knew about the Crouth and it was a Kelt, a Welshman named Morgan, who had last played upon the Crouth in the beginning of the eighteenth century. For there had come the violin, a hundred years before Morgan died, and Gasparo di Salo showed his art to Magini, and the Amatis carried it on and Guarnerius and Stradivarius brought it to perfection, and was his own violin not a Strad, priceless and unpurchaseable? He would leave it to Wilhelmj or another master, he said, when he passed, but he thought that the great Master of all music might one day come to him to assure him that music would be perfect on earth as it was in heaven. He lived for that. Orpheus had descended into hell to save the lost one. It was the gospel. There was no hell the Master would not enter if it might profit. And who might Orpheus be but one of the great Gods, the bright ones, the heavenly powers that came to earth when it grew dark with ignorance and failure? So he talked and for another twenty years he was a familiar figure about the little town, erect, one-armed, clear-eyed, ascetic, silken-bearded, a gentle influence in the community. [page 12]

IT USED TO BE ABOUT that at night people, passing his tiny cottage where he lived alone, heard music strangely sweet and thrilling. Sometimes strangers visited him to play upon his violin, but it was never known that any lodged with him. It was whispered that he always prepared his table for a guest, and that he lived in daily expectation of the presence of some great one for whom he lived to be worthy, pure in thought and heart and body. It was remembered, too, that once he remarked that He who had descended into hell would not shun the dwelling of the humble. Afterwards, when the funeral was over, one who had passed Armand’s cottage late the night before he had been found lifeless, told of coming through the bitter storm that had been raging, the keen blast filled with icy particles, and of hearing through the tempest, above all its buffets, a sound of heavenly sweetness, and as he came near the cottage that there shone through the chinks of the door and the window-corners a radiance as of the sun at noonday in its splendour, and over all the freezing assaults of the wind and snow as he passed there was suffused a mild and gentle warmth as of midsummer by the sea. It was so marvellous that the [page 13] passer-by feared for himself, distrusting his senses and rapt into an ecstasy with the wonderful music he heard, such as he did not think earth could produce. Next day they found Armand kneeling before his little table, with a strange little flower in his hand, like a narcissus blossom, and his face bowed on his arm as it rested on the table. They said his face had a look as of one who had taken a sacrament. On the other side of the table a chair had been pushed back, as where one had risen. There were broken bread and a cup on that side of the table, and the violin and the bow were liad down as by some one who had been playing. [page 14]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.