|

Essay 18 The Canadian National War Memorial: Jim Zucchero

|

||||||

I On April 10, 1997 The Globe and Mail carried a front page photograph of a Canadian standing on the Canadian War Memorial in Vimy, France. The caption beneath the photograph reads:

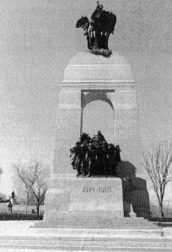

It is not surprising that the anniversary of a significant military battle should be recognized in Canada’s newspaper of record. What is remarkable is the fact that fully eighty years after the Battle of Vimy Ridge, "Canada’s National Newspaper" continues to assert its importance as a crucial event in Canada’s transformation from "mere colony" to mature nation. The particular importance of the First World War on the Canadian national psyche has been widely recognized for some time by historians and seems, if anything, to grow more pronounced and more certain as time passes.1 Does the fact that each year fewer and fewer veterans of those battles are among us to commemorate these anniversaries serve to heighten our appreciation of the importance of those events? What is the nature of the relationship between our public war monuments and our sense of national identity? The Vimy photograph and caption serve as a powerful and graphic reminder of the continuing significance of war memory and war memorials in Canadian culture.2 Granting the continuing significance of the First World War for Canadians’ sense of their country and themselves, the question that confronts a cultural historian who attempts to guage the nature of contemporary responses to the War is one of how to unravel or uncover the shifting representations, sentiments, impulses and responses that war memorials like the one in Vimy, and the Canadian National War Memorial in Ottawa, bear for Canadians today. What is certain is that these war memorials must be interpreted through various filters: the layers of discourse that include academic and historical writing, social and cultural criticism, government publications (past and current), literature,3 poetry, journalism and so on. According to Andreas Huyssen, who addresses some of these issues with great acuity in Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (1995), this vast array of discourses is as essential and indispensable to the life of the monument as the monument itself is to the ongoing creation of collective consciousness. "How, after all, are we to guarantee the survival of memory if our culture does not provide memorial spaces that help construct and nurture collective memory?", asks Huyssen, and his answer bears directly on Canadian war memorials: "[o]nly if we focus on the public function of the monument, embed in it public discourses of collective memory, can the danger of monumental ossification be avoided" (258). In the belief that "monumental ossification" is to be avoided in the interest of preserving national and personal identity, in an age where both are under increasing threat, the essay underway is an attempt to guage the significance of the Canadian National War Memorial to Canada and to Canadians at the close of the century and the millennium. The discussion will examine the relationships between "cultural memory," monuments—in particular Canada’s National War Memorial in Ottawa—and the idea of national identity, or, in Maurice Halbwachs’ phrase, "collective memory."4 The essay will also consider the ways in which the meaning and significance of monuments can and does shift in time and the effects of "generational distance" on the ways in which monuments are viewed and interpreted, and it will seek to demonstrate that the Canadian National War Memorial continues to function as a metaphor for "the birth of the nation."5 II In To Mark Our Place: a History of Canadian War Memorials (1987), Mark Shipley provides a brief description of the National War Memorial that highlights its principal features:

Like any work of art, the National War Memorial can, to some extent, be "read" like a text. Among its most striking features are its physical dimensions (it reaches a height of 21 metres or about 70 feet) and the number of figures depicted (twenty-two in all). Since the figures themselves are one third greater than life size, they are both literally and figuratively ‘larger than life,’ a reflection in scale

of the esteem if not awe that they are intended to inspire. Prominent features of the Memorial are two horses and riders, a classical motif that will resonate for most viewers through association with other equestrian statues in Europe or North America. Neither in the walking or mounted figures is there any expression of pain or anguish; rather the figures seem to convey pride, longing, defiance, a strong sense of purpose, vacancy, camaraderie and perhaps a touch of dejection, but mostly firm resolve. All in all, the Memorial is multi-dimensional and multi-faceted in its physical and emotional appeal; it provides much to see, to feel and to ponder. A very strong sense of realism is conveyed in the draping of the cloth on tattered and frayed uniforms; the pug noses and gritty faces are also realistic and affecting. These figures are not polished or in parade form but, rather appear to strain under the weight of their load (physically, mentally and emotionally) as they wield their heavy packs and weapons. The Memorial bears no written inscription other than the dates: 1914-1918 (on two sides—the east and west faces); 1939-1945 (on the north face); and 1950-1953 (on the south face). The omission of any written inscription may have provided a convenient means of avoiding the difficult issue of the two languages, English and French, widely used in Canada. Atop the great stone arch are the allegorical figures of Peace and Freedom, which are described in the Veterans Affairs publication The National War Memorial (1982) as follows:

Ideally, then, peace and freedom are the byproducts of the sacrifice, won by the people’s heroism, like the myth of the phoenix rising from the ashes of the ruins. The symbolism of the allegorical figures portrays vividly the officially sanctioned preference to dwell on the purposefulness and heroism of war as opposed to its horror and futility. It also contributes to the sense that the Memorial depicts the birth of Canada by implying that in war the nation’s welfare as a whole is served by the sacrifices of individuals. Almost every aspect of the Memorial, including its location and materials, is rich in significance. The question of where to locate it

was the subject of lengthy debate and, almost needless to say, the site that was finally agreed upon—Confederation Square—has considerable symbolic importance on account of its association with the unity of the people of Canada.6 Moreover, the monument stands opposite the Parliament Buildings, so it has as its backdrop the seat of the Canadian government, the Peace Tower, and other structures of national importance. The very materials from which the Memorial is constructed—granite from a quarry in Quebec and bronze shaped by a British artist—have cultural and historical significance. Because it is constructed out of bronze and granite the National War Memorial has changed and will continue to change in appearance over the years through exposure to the elements and to urban pollution. The Memorial is concerned with conveying memories from one generation to the next and the subtle malleability of its materials seems wonderfully well-suited both to this purpose and to the delicate nature of memory itself. As the artist Vernon March himself noted: the idea was "to perpetuate in this bronze group the people of Canada who went Overseas to the Great War, and to represent them, as we of today saw them, as a record for future generations" (Gardam 5).

But, arguably the principal repository of the sculpture’s significance is the arch that constitutes its unifying structure: as they struggle through its opening in battle, youth do not merely move towards victory; they enact a rite of passage, a birth that will earn their country a place in the community of nations, a community governed by peace and freedom. Inseparably linked as they are, the figures of Peace and Freedom that surmount the arch speak both to Canada’s participation in the struggle to achieve lasting stability and democratic values that resulted in the creation of the League of Nations, and to the hope that in Canada itself peace and freedom may continue to triumph over the forces of instability and the tyrannies of ethnicity. The First World War was indeed a "searing experience" for Canada, to use Pierre Berton’s phrase—in the personal lives of those who served or were touched by the War, and in the broader sense, for the young nation struggling to find its place and establish its identity in a new emerging world order. III In order to appreciate the ways in which the Canadian National War Memorial partakes of the general characteristics of war memorials it is important, first, to establish a working definition of the term "war memorial", and, second, to consider briefly some of the history of war memorials in general. In War Memorials as Political Landscape (1988), James Mayo suggests that "the strengths and weaknesses of a society are demonstrated in war and memorials to those wars often mirror those same qualities. War is the ultimate political conflict, and attempts to commemorate it unavoidably create a distinct political landscape" (1). If Mayo’s preliminary assertion—that a nation’s strengths and weaknesses are demonstrated in war, seems questionable7, his principal point that war memorials unavoidably create a distinct political landscape, seems more secure, as does his ensuing definition of a war memorial:

As a supplement to the definition of memorial space, Mayo offers the suggestion that "[a]ny war memory that is bound to a place or artifact can be a war memorial" (4), a "war memory" being any recalling of personal experiences of war or culturally transmitted ideas of war by an individual. Both Mayo’s primary and supplementary definitions are useful because they point to the inherently dualistic nature of war memorials: the memorial as both object—the statue in the park—and as act—the act of remembering or constructing mental images, perhaps stimulated by some artifact or text related to war. The idea of war memorial as act of remembrance is important, not only as it relates to the annual commemoration day (November 11) that is widely observed, but also as it relates to individual, personal experiences of "remembering" and, as important, the susceptibility of remembrance to manipulation by those who would seek to control the future by controlling the past. 8 Indeed, the history of war memorials shows that they have very often been used to influence public, collective consciousness down through the ages. Writing of the culture of classical Greece and Rome in which the modern, Western war monument had its origins, Mayo observes that "as these cultures developed, attempts were made to translate societal values into built form. The two dominant themes portrayed in war memorials at this time were religious expression and proclamation of victory, but mourning and re-creation of the human spirit were also present" (10). Mayo emphasizes the point that, from their earliest incarnation, war memorials have attempted to translate values into forms, that the material object is somehow to be seen as an emblem of intangible spirit, a tradition that, like the components of the monuments themselves, has lasted into the present century with little in the way of innovation or development (at least until very recently, when we see design and execution of monuments move beyond classical approaches).9 In short, and as Mayo again observes, the war memorial has been extremely resistant to change, evolution and development and, for a variety of reasons, can be regarded as a quintessentially "conservative" form.The "conservatism" of war memorials is explored by George L. Mosse in Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars (1990). Like Mayo, Mosse relates the resistance of war memorials to change to broad social and cultural phenomena, pointing out that what he calls "the cult of the fallen" is a profoundly conservative phenomenon. "[W]henever modern or experimental forms [of war memorials] were suggested or even built," he writes, "they aroused a storm of opposition and proved ineffective" (103), because they appeared to surrender the connection between the preservation of a memory and the appeal to tradition. Since war memorials, at one level, seek to freeze events, images and emotions in time, it is not surprising that they resist experimental approaches in form, media and theme. For Mosse the essential conservatism of the war memorial reveals "the nature of the cult of the war dead as a civic religion" and he draws close parallels between war commemoration and religious observances: "[r]eligious services, the liturgy, have always proved singularly resistant to change…. Moreover, the liturgy of the fallen had a special urgency about it, for it formed a bridge from the horror to the glory of war and from the despair of the present to hope for the future" (104). In addition, Mosse identifies the war memorial as national sentiment writ large, a projection of a culture or nation’s collective consciousness of itself: "[e]verywhere the cult of the war dead was linked to the self representation of the nation. The civic religion of nationalism used classical and Christian themes, as well as the native landscape to project its image" (105). One other significant and pervasive characteristic of modern war memorials is brought to light in Mosse’s discussion—namely, the tendency for them to focus on the collective efforts involved in military struggle as opposed to individual acts of a heroic nature: "[m]odern war memorials did not so much focus upon one man as upon figures symbolic of the nation—upon the sacrifice of all its men" (47). This point is clearly demonstrated in the Canadian National War Memorial. It depicts a large group of men and women, both soldiers and support service workers, and speaks first and foremost, as will be seen, to Canada’s collective contribution to the war. 10For Mayo and Mosse, the war memorial serves a clear public function: it focuses the attention of the public on specific events of the past in order to foster a collective orientation toward those events and to keep their memory alive in some consistent way in the present day. Both writers strongly emphasize the traditional, conservative nature of the war memorial as representing a culture to itself for the purpose of binding it together. A valuable supplement to their approach is found in Andreas Huyssen’s Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (1995), where the conservative function of the memorial is acknowledged but placed in the context of the heterogeneity and globalization of contemporary cultures and the effect this has had on the monument’s mode of functioning. Huyssen’s central thesis is that, far from negating the importance of the monument, heterogeneity and globalization render memorials, and especially war memorials, more vital than ever in keeping alive the memory of past events and in animating the dialogue that helps us to impart specific and varied interpretations to those events. In his view, the monument avoids the problem of "monumental ossification" precisely by pointing us to other texts and stories. In relating the monument to questions of identity, Huyssen rejects monolithic notions of identity, both personal and national, and contends that modern identity is necessarily heterogeneous and fluid. "Remembrance shapes our links to the past and the ways we remember define us in the present", he writes; "[w]e know how slippery and unreliable personal memory can be…. But a society’s collective memory is no less contingent, no less unstable, its shape by no means permanent. It is always subject to subtle and not so subtle reconstruction" (249). So what are the forces that are working, subtly or not, to affect our construction of collective consciousness? And why is it important to consider these forces? For Huyssen the answer relates directly to the notion of the viability of a culture, based on an appreciation of difference that can only be achieved by means of a thorough understanding of the past: "[w]ithout memory, without reading the traces of the past there can be no recognition of difference…no tolerance for the rich complexities and instabilities of personal and cultural, political and national identities" (252). Huyssen goes on to suggest that "the desire to articulate memory in stone," the collective impulse toward memorialization, is to a large extent a function of individual and collective awareness (perhaps even despair) at "the quickening pace of material life" and the fleeting temporality of the media images that surround people in the late twentieth century. Recognizing in the permanence of the monument a quality that fulfils a societal need at a time when life is increasingly characterized by change and temporality, he suggests that "the museum, the monument and the memorial have taken a new lease on life" in part because they offer something that television denies: "[i]t is the permanence of the monument in a reclaimed public space that attracts a public dissatisfied with simulation and channel-flicking" (254).11 In the case of war memorials, Huyssen contends that these monuments are able to have an impact in part because of the generational distance that is opening up between the events commemorated and the audience. Rather than bringing about irrelevance, this increasing temporal distance has "freed memory to focus on more than just the facts. In general we have become increasingly conscious of how social and collective memory is constructed through a variety of discourses and layers of representation" (256). It is as though we are now far enough removed from those painful events that we can safely remove our blinkers. We have, in time, gained the requisite critical sophistication to consider those events in a new light, to consider not only the ‘what’ but also the ‘how’. Huyssen’s discussion of monuments makes a number of valid and stimulating points, many of which can be applied to an analysis of the Canadian National War Memorial. And yet, there is a peculiar sense in which his thesis was anticipated by the Canadian War Memorial. In essence Huyssen argues that historically, war memorials have attempted to hold up some monolithic symbol to a homogeneous group or culture, and that now the war monument must attempt to take that static symbol and make it speak to a heterogeneous culture. In many ways the Canadian National War Memorial has always done this, because of the specific nature of Canadian culture. To a great extent, the heterogeneity the Huyssen identifies as a central characteristic of post-modern culture has always been present in Canada (though certainly to a far greater extent now than at the time of the First World War), and has been recognized from the outset in Canada’s National War Memorial. It can be shown that the Canadian National War Memorial was conceived, created and has continued to function as a means of negotiating essential and elementary differences inherent in Canada—a nation that has historically seen two nations at war and in war. The extent to which the Canadian case illustrates this point can be traced by examining how the meaning, significance and interpretation of the memorial have changed, or more precisely, been manipulated, by various agents, means and processes, to negotiate the shifting sensibilities of the Canadian public. Certainly the Canadian Memorial partakes, in some ways, of the conservative characteristics noted by Mayo and Mosse, characteristics that are necessarily part of the nature of war memorials; but it also demonstrates admirably the ability to negotiate the differences to which Huyssen refers, differences that are more prevalent and more complex today than they were in Canadian society of some eighty years ago. IV The national sentiment that prevailed in Canada on the subject of commemorating the Canadians who were killed in the First World War is reflected in the debates that took place in the House of Commons before the War ended and continued sporadically for more than two decades. These records provide a detailed chronology of events over the years leading up to the creation of the National War Memorial, and, moreover, demonstrate that the movement to create the monument was not unanimous or without its detractors. In fact, given that the debate lasted throughout the Great Depression, it is not surprising that the focus of dissent was not around the merit of recognizing and honouring the war dead, but rather on the propriety of undertaking such an expenditure instead of directing those funds to the needy, particularly needy veterans. On April 29, 1918, more than six months before the end of the War, Prime Minister Robert Borden rose in the House to announce the establishment, largely through the initiative of the expatriate entrepreneur Lord Beaverbrook, of the Canadian War Memorial Fund. "The purpose of the Canadian War Memorial Fund," Borden said, "is by paintings, by photographs and by the erection of memorials, to aid in perpetuating the memory of what Canada has accomplished in this war" (Canada, Debates of the House of Commons, 1918, 1195). Although from the very outset of discussions at the government level, art and remembrance of the War were thus linked, in 1919, following the end of the War, the focus of attention was on the burial of the war dead. Certain principles were agreed upon: that the headstones over the graves of soldiers and officers would be the same, for "[t]hey are all equal in death" (Debates, 1919, 1058); that each regiment should be consulted as to the design of its marker; and that each family should be allowed to add a short inscription or prayer to "personalize" their stone. More contentious was a question that anticipates the debate surrounding the National War Memorial by raising the issue of Canada’s status in relation to Britain: "[w]ill the graves of our Canadian boys who were killed while in the Imperial army be marked with any distinctive Canadian emblem, or will they bear the Imperial emblem?" (Debates, 1919, 1061). No answer was forthcoming but there were assurances that the issue would be raised. At the outset, then, the issue of commemoration was closely interwoven with issues of collective and national identity: be they simple, individual grave markers or elaborate national monuments, memorials to the Canadians killed in the First World War would stand as a testament to Canada itself. Nowhere was the recognition of Canadian losses and the conviction of national achievement more evident than in discussions pertaining to the site of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. On May 22, 1922 William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had been Prime Minister since December 1921, proposed that the battleground itself should be purchased12 by Canada and dedicated as a permanent memorial, "one of the world’s great altars [to those who] sacrificed in the cause of the world’s freedom" (Debates, 1922, 2099). Another member of the House, the Hon. Sydney Chilton Mewburn (Unionist—Hamilton East), added that Vimy was not the most important battle but "there is something distinctive regarding Vimy that comes very close to the hearts of Canadians" (Debates, 1922, 2099). Writing more than sixty years later, the historian Desmond Morton corroborates Mewburn’s sentiments about the special status of Vimy in the hearts and minds of Canadians, describing the battle with an emphasis on the time of its occurrence that links it to the death and resurrection of Christ:

Morton’s rhetoric, his use of phrases such as "seemingly impossible," "done together," "equal pride," and "created nations," underscores the quality of heroic self-sacrifice that he finds in the action. The potential of Vimy Ridge and other battles in which "English and French could take equal pride" to draw the country together, not only in the immediate aftermath of the War (and a divisive conscription crisis) but also in the decades to come, was as apparent to politicans at the time as it would be to subsequent historians. And what better way to translate the death of 60, 000 Canadians into a statement of national unity than in the form of a National War Memorial in Canada’s capital city? The specific initiative to create a National War Memorial came on May 11, 1923 when King stood in the House of Commons and inquired about erecting "a national monument in the capital city of Canada, to commemorate the deeds of our men overseas, a monument of a national character such as would express the sentiment of the nation in that regard" (Debates, 1923, 2685). Clearly it was a tall order to create a single work of public art that could somehow synthesize and embrace the sentiments of the entire nation, but King noted that the government had received representations from different quarters and that "such a monument was rather expected on the part of the Canadian people" (Debates, 1923, 2686). (Shipley points out that across the country, small, grassroots local organizations, had enjoyed enormous success in raising funds to erect local war memorials to commemorate members of their communities who had served in the Great War. Small committees were often formed by women’s groups, such as the I.O.D.E., and veterans groups and they often relied upon emotionally charged rhetoric in their campaigns to elicit financial support for their projects.) 13 As the debate surrounding the creation of a national war monument gathered momentum, it was suggested that Canada should "aspire to something loftier than a monument in stone" (Debates, 1923, 2688) and that, in view of Canada’s status as a new, modern nation, there should be no hasty decision "to follow precedent, to follow the ancient countries" (Debates, 1923, 2688/2689). Answering the criticism that the creation of a national war memorial would entail giving "a dead soldier…more than a living one," King defended the initiative with some emotionally charged ideas and rhetoric: "[w]hen a nation loses what is signified by its art it loses its own spirit…. When it loses the remembrance of the sacrifices and heroism by which it has gained the liberty it enjoys, it loses all the vision that makes its people great" (Debates, 1923, 2689). It is clear from the language of this speech that, in King’s estimation, a national war memorial could be, should be, and must be instrumental in its symbolic representation of national pride and in its capacity to inspire future generations of Canadians to such acts of courage, sacrifice, strength and honour as had distinguished the country’s war dead. This was the stuff of which great nations were made and Canada could do no less than to celebrate it in a deserving fashion.Some three years later, in January, 1926 the contract for the National War Memorial was awarded to the British sculptor Vernon March, whose design had been selected from 127 entries in an open competition. Over the next several years numerous revisions and adjustments to the original contract were authorized; figures were added, dimensions were enlarged; and with each alteration the cost of the project increased. These cost increases merely served to heighten the opposition to the project which, from the start, had been quite vociferous in some quarters. On June 19, 1931 James Shaver Woodsworth, the Labour MP from Winnipeg, rose in the House of Commons to inquire as to the cost of the national war monument. 14 He was told that the original contract was for $135, 000, and that two additional figures had been added bringing the new cost to $145, 000. He quipped: "[i]f there is a contract…we must go through with it…but with poor unemployed soldiers in the country, I do not think we shall need many monuments for a while" (Debates, 1931, 2853). With the country now plunged into the depression the spiralling cost of the Memorial created, for some, an ethical dilemma and a crisis of conscience that was played out publicly in a debate whose divisiveness was, ironically, a complete inversion of the sentiments and qualities that the National War Memorial was seeking to honour and cultivate. If the rhetoric of the appeals to raise funds for local war memorials was emotional and hyperbolic, the scenes painted by those in opposition to the National War Memorial were no less so. By 1939 the cost of the project, which now included the construction of terraces at the site and the re-routing of traffic in downtown Ottawa to accommodate it, had climbed to over one million dollars, prompting Alonzo Bowen Hyndman (Conservative—Carleton) to rise in the House and deliver this scathing attack:We now have a memorial there which is costing over

$1,300,000… but if those soldiers were to come back to-day and look at

the memorial…and realize that $1,300,000 was being spent on it, while

[their] sons and daughters…are walking the streets of Ottawa hungry,

barefoot and without jobs…. No wonder the sculptor has depicted the

soldiers going through the arch with their heads hanging down, as though

perplexed at what is going on. Perhaps they are dizzy at the way the

traffic is handled around that square. For some, the bitterness hardly seemed to abate even in the afterglow following King George VI’s dedication of the sculpture in the redesigned city centre on May 21, 1939. Indeed, one Member of Parliament went so far as to claim that he was struck by the thought that "there were veterans on parade who were unemployed, who could not get work on relief roles [and who would] go back from the parade to a life of no hope" (Debates, 1939, 4442). These sentiments, while typical of those who did not support the national war memorial initiative, were by all accounts not the sentiments that prevailed amidst the euphoria that surrounded the royal visit of 1939. The dedication of the monument by the King was generally regarded as a great triumph and just cause for celebration. And nothing could have had a greater impact in setting this tone of pride and honour than the King’s own speech at the unveiling ceremony at the newly christened Confederation Square. V The speech that King George VI gave at the unveiling is striking in two ways: it is a carefully crafted piece of rhetoric, and it draws on images and metaphors that are stirring and memorable. Superficially, the speech appears to be a tribute to Canada, the dutiful colony, for answering the call of the motherland in a time of need, but closer examination shows that the emphasis lies elsewhere. What is really celebrated in the speech is a vital young country’s achievement of nationhood, Canada’s entry into the community of Western nations through her support of the fundamental principles of decency and democracy. The entire text of the King’s speech appeared in The Globe and Mail on Monday, May 22, 1939, as follows:

TEXT OF KING’S SPEECH AT MEMORIAL UNVEILING

"Answer Made by Canada"

With masterful rhetoric and admirable concision, 15 the speech not only reinforces the myth of Canada’s birth as a nation through war service16 (more of which in a moment), but also touches upon many of the characteristics of war memorials that were discussed earlier. Referring as it does to "Canada’s spirit and sacrifice," the opening sentence illustrates Mayo’s point that war memorials attempt to be emblematic of human, and in this case national, spirit. Linking war memories with the reign of the previous king, the second paragraph alludes to the enduring British Empire and, in so doing, creates an appeal to the audience’s sense of loyalty while also attempting to provide a subtle reassurance that stability is at hand in the form of the monarchy and its associations and continuities. Identifying the monument as "an enduring expression" of "the spirit of Canada," the remainder of the same paragraph reinforces the traditional role of the monument as manifesting human and national spirit, and providing a permanent touchstone for this association. The third paragraph, with its reference to "the time and place of [the] ceremony," can be read as a deft diplomatic handling of the controversy and the delay in erecting our national memorial to those who had died a full generation ago, but it is also an oblique way of acknowledging that other nations in Europe and "throughout the Dominion" have recognized the great sacrifice made and the service provided by Canadians during those difficult times.With the shift signified by the (interpolated) subtitle "Answer Made by Canada," the speech begins to propose its essential message about Canada’s status in the community of nations by focusing on the rich symbolism of the Memorial. By suggesting that "the memorial speaks to the world of Canada’s heart," the King implies that the monument was intended as a very conscious effort to declare to the broader international community that Canada has played its part and done so honourably. (Although the two are not mutually exclusive, this is a very different purpose from the honouring of those who fell.) Twice in the space of three sentences mention is made of "the world," as if to underscore the idea that Canada has played a significant role in global affairs. In the same sentences, mention is also made of the symbolism of the sculpture and its title "The Response" and in ensuing sentences the significance of its symbolism is described and elaborated: not only does "the response" encompass service to the community of nations, but it also conveys, in the King’s estimation, something more profound: a deeply felt appreciation of conscience. In an interesting turn, the King contrasts chivalry, which might be associated with love and emotions, to conscience, a somewhat loftier ideal because it involves reason and morality. The inference here is that in this "spontaneous response of the nation’s conscience" Canadians have truly distinguished themselves as worthy of full rank and status among the world’s great nations. The King next explores and interprets the sculptural elements of the Memorial and once again uses the opportunity to emphasize the new status of Canada as a result of the service rendered. Noting that "the armed forces of the nation are passing forward," he implies that the forward motion represents a progression, a movement in time and an advance in values that will be "held in remembrance" through the Memorial for "succeeding generations." Nor does the Memorial merely "commemorate a great event in the past" for succeeding generations in one country; rather, it conveys a universal message "for all generations and for all countries"—a "great truth" that is emphasized rhetorically not only through sonorous repetition ("for all generations and for all countries") but also through a chiasmic transposition of the terms "peace and freedom" that affirms their inseparability: "[w]ithout freedom there can be no enduring peace, and without peace no enduring freedom." It is difficult to doubt that when he spoke these words in Ottawa in May 1939, George VI did not have his eye as much on the part that Canada would play in the conflict then looming in Europe as on the part she had played in the conflict that ended over two decades earlier. There could be few better examples than George VI’s speech at the unveiling of the National War Memorial of the process by which, in Mayo’s words, a "war memorial" both "keep[s] alive the memories of those who were involved in a war" and "helps [to] create an ongoing order." For further insight into the nature of that "ongoing order" a few moments may be taken by way of the conclusion to examine The National War Memorial, a booklet that was published by the Government of Canada’s Department of Veterans Affairs in 1982 and is still in circulation today. VI The National War Memorial is an impressive publication. Enclosed between colour photographs that depict the Memorial by day and at night, it runs to 46 pages and includes as many black and white photographs. Written by John Gardam and Patricia Giesler, it is divided into two distinct parts, each of which has a specific objective: the first, entitled "The Response," recounts the story of the history and construction of the monument; the second, entitled "The Memorial," provides a brief history of Canada’s involvement in the First World War, principally by commenting on the individual figures in the Memorial which are depicted in individual, close-up photographs on each page. In tandem, the two parts constitute a classic teach and delight approach to providing information. A careful examination of the text of the brochure reveals several recurring motifs and strategies that encourage the reader to continue seeing the Memorial as a metaphor for the birth of the nation. Even in the opening paragraph of the brochure description is blended with interpretation and an assertion of the symbolic importance of the Memorial:

The fact that the Memorial was unveiled to recognize specific past events and has since come to symbolize the sacrifices of later generations of veterans who served in other conflicts, suggests that its original meaning has been added to, that it has somehow metamorphosed as Canada became involved in successive great conflicts, and that it participates, in this way, in a national evolution that nevertheless remains true to the first principles of "peace and freedom." The Memorial, installed in a prominent public space in 1939, has now become an element of the landscape that is absorbed and reflected, almost in an organic way, by the society in which it exists. The text of the brochure frequently takes up language that is elevated and at times even poetic, presumably to heighten the reader’s sense of reverence for the Memorial and the remembrance it seeks to perpetuate. For example, the First World War is said to have called for unprecedented sacrifice "from the people of a still young and struggling nation. The response was magnificent," and it is suggested that the Memorial was created to keep alive "the spirit of heroism, the spirit of self-sacrifice, the spirit of all that is noble and great that was exemplified in the lives of those sacrificed in the Great War" (4). With the phrase "all that is noble and great" the reader is transported into the realm of the abstract and even the mythic. This is the sort of poetic language that reaches into a realm of ideas and actions that lies beyond the grasp of the common citizen, that gestures towards epic struggles and the high mimetic mode which, as Northrop Frye suggests, corresponds to the qualities and deeds of heroes and gods. 17 Arguably, it is precisely this level of diction and this level of thinking and representation that is needed to anchor a notion as big as the founding of a nation. A transcendent idea such as "national identity" seeks, craves, demands lofty words and ideals on which to fasten and feed if it is to sustain itself, and the theatre of war is surely one of the few stages that is capable of providing the background, the scene, the action and the emotional pitch required to sustain such a weighty and, some would say, unlikely concept.18Periodically, the brochure makes use of the unveiling of the Memorial and the speech by the King in recounting the Memorial’s history and reinforcing its national significance. Several photos of the scene in the square at the time of the dedication surround one of the King delivering his address, but the speech itself is reproduced in the brochure in an interestingly abridged form: the first portion of the speech, in which the King spoke about the British Empire and his father’s reign, is omitted entirely and the second part, celebrating Canada’s response to the War, is reproduced in its entirety. The line at the centre of the excerpt is: "[t]o win peace and secure freedom Canada’s sons and daughters enrolled in service during the Great War. For the cause of peace and freedom 60, 000 Canadians gave their lives…" (12). The result of these editorial omissions and additions is a de-emphasis of Canada’s imperial connections and an emphasis on the country’s birth as a nation dedicated to the ideals of "peace and freedom" in and through the First World War. The centrespread of the booklet is a collage of photographs of the Memorial from various perspectives. It also employs two brief excerpts of poetry: one in French—three lines from Jean Pariseau’s "Au champs d’honneur"—and one in English—the final three lines of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." McCrae’s poem provides what may be the best known lines of English poetry about the First World War and the inclusion of his lines here can be seen as both showcasing Canada’s most famous war poet and providing subtle but significant support to the ‘birth of the nation’ concept. The remainder of the publication is dedicated to providing detailed cameos of each of the branches of the service that were engaged in the war. These profiles clearly attempt to provide factual information, such as statistics, dimensions, names of people and places. They also paint a canvas on which the actions of Canadian soldiers can be seen as extraordinary, magnificent and heroic. A vivid example is provided in a passage that describes the photograph of the infantryman on the Memorial: "[t]he respirator he is wearing was a significant item in a soldier’s kit for poison chlorine gas was introduced by the Germans at Ypres, Belgium in 1915, in an attempt to break the stalemate of the trench warfare. In holding their lines in the face of this deadly new weapon Canadians established a reputation as a formidable fighting force" (25). The last sentence of this passage especially represents Canadians as an heroic people and, in the phrase "established a reputation," reinforces the sense that Canada came of age as a nation at such battles as Ypres (the compositional site, perhaps not coincidentally, of "In Flanders Fields").19 Other segments of the brochure attempt to tell the story of Canada’s First World War veterans in a distinctly personal manner. Precise details are inserted to accomplish this, as for example with the description of an infantryman’s curly moustache as "the soldier’s garden" (27). Yet here, too, the language of the brochure also approaches the poetic in some passages, as with the alliteration of phrases such as "the realities of dirt, disease and death" (27). This tendency toward poetic narrative becomes problematic however when the text is used as a point of departure for highly conjectural assertions that are unfounded and which appear to be present for the sole purpose of contributing to the brochure’s prevailing motif of nation building. A case in point is another description of one of the figures on the Memorial:

The speculative tone of "he might well represent" does at least indicate the speculative nature of the attempt to make the Memorial more representative than it actually is, but this scarcely excuses the text’s elision of many of the unpalatable facts surrounding the involvement of Native Canadians in service in the wars. For example, the reader is not informed that they had to give up their Native status to serve in the Canadian Armed Forces in the World Wars; that they were denied the same rights and benefits as other veterans when they returned home after the war; or that they were unable to rejoin their Native communities upon their return because they had given up their Native status. 20 "Natives who wanted to serve their King and country," observes Daniel G. Dancocks in Welcome to Flanders Fields (1988), "found they were not wanted" (42). Such facts are not woven into the fabric of the official government publication, because they obviously do not fit neatly into the framework of the myth of nation building through collective effort and common purpose. Indeed, when these and other factual omissions are recognized, it can be seen that the text of the brochure is quite clearly tailored and constructed in order to foster a selective, officially sanctioned version of events. At best this sort of selective narration can be seen as an ill-conceived, if well-intentioned, attempt to recognize and honour Native veterans; at worst it is a shameful manipulation of facts to construct a fiction for the purpose of fostering a feel-good response among ill-informed and unsuspecting readers. The inclusiveness that is apparently the objective of the passage relating to Native Canadian veterans is one of the dominant characteristics of the remainder of the brochure, both in textual and graphic representation.The concluding pages of the brochure constitute a virtual catalogue of the various branches of the services that Canada contributed to the war effort. Great efforts are made to recognize the contribution of each distinct group and the important role its members played in the final victory. This portion of the text also emphasizes the most highly romanticized and mythic elements associated with each group. The Highland Scots are remembered as brave young men, fierce fighters (—and good pipers) (29); the terrible loss of young people in war is remarked upon (30); there is mention of the growth of the Canadian Navy during the war from an "embryonic naval service [with] a handful of men in 1914" to a force of more than 5,500 men in 1918 (33)—a reference to growth that once again reinforces the nation building myth. The romantic myth of the First World World War flying ace is predictably exploited, and the common stereotype reinforced with the mention that: "the men who flew the rickety planes with few instruments and no parachutes had a glimpse of the fame and glory once expected of war" (35). Parts of the text do provide useful and accurate observations about the nature of warfare at this time; for example, the discussion of the cavalry soldier states: "the introduction of the machine gun and the tank spelled the end of cavalry warfare" (36) and the skills of Canadian engineers in preparing battlefields for the advance of troops, is discussed (37). Here again, however, the text is reductionist and exclusive for by focusing on one Canadian engineer who won a Victoria Cross for extraordinary acts of bravery, but not mentioning the dozens or perhaps hundreds of men who only swung picks, it attempts to create and perpetuate an attractive myth. As if to suggest the existence of post-war Canadian society in microcosm in the various units of Canada’s war-time forces, the concluding pages of the booklet describe the activities of the Canadian railway troops, the Canadian Forestry Corps, and those involved with communications and medical services. Finally, while the sculpture itself is a tableau, a frozen scene, the text of the brochure narrates a story behind the scene often at a mythic level and, in doing so, it conflates its sometimes contradictory impulses toward realism and national mythology. VII It is arguable that in the late nineteen nineties the Canadian National War Memorial does not and cannot contain, foster or manifest the same sort of national sentiment in relation to the First World War, or war in general, that it held in 1939—when it was unveiled by the King of England; or in the 1920s and ’30s—when it was conceived and debated during the Great Depression. Today Canadians are compelled, by the very nature of their experience, to view this Memorial (and all memorials) within the broader context of the constellation of texts and discourses that come to mind when it is viewed or remembered. The Canadian National War Memorial demands to be interpreted in the light of Huyssen’s observations about the ways in which monuments—especially war monuments—function in post-modernist culture;—their work as mediators between the abstract and the human, as gestures towards a monolithic national identity that, despite their creators' intentions, evoke a recognition of social heterogeneity and difference. Today the Canadian National War Memorial is associated with more than one war, more than one poem, more than one sense of Canada’s past achievements and present state. To different viewers it will recall Alden Nowlan’s "Ypres, 1915", the image and voice of Private Billy McNally and the TV veteran of Vimy, with his rats and water. Now it is surrounded with texts and characters, both real and fictional, who are insistently memorable for their thoughts, actions and words. So the voice of King George VI, at the unveiling of the monument, and his profound reflection on the inseparability of peace and freedom, lingers around the Memorial (albeit in truncated form) in The National War Memorial booklet. So the human interest stories, taken up by journalists alongside the coverage of the ‘main event’—about the mother who lost five of her eleven sons who saw action in France—also join the associations of the Memorial. Images and stories like hers, because they challenge us to comprehend the crushing weight of such a loss, become a vital part of the discourse through which the meanings of the Canadian National War Memorial itself are approached. Speaking personally, I cannot view the National War Memorial now, in 1997, without thinking of the photograph that graced the front page of The Globe and Mail on November 12, 1996: it shows the deeply creviced face of a Second World War veteran with a tear in his eye. And I cannot help but ask the obvious question: why? What is he remembering? The Canadian National War Memorial is a fascinating case study of how a modern nation grapples with questions of self-definition. As both an inert object and a catalyst in a dynamic process, the Memorial raises difficult questions about identity. As a collectivity, what do Canadians choose to identify themselves with and by? How was and is the Canadian search for collective identity reflected in the object and the discourse that is the Memorial? The history of the Canadian National War Memorial, and the manipulation of its significance, reveal the complex ways in which identity, no less than artefacts, are both given and constructed. They suggest that Canadians will probably continue to define themselves around issues of values, such as democracy; around events in time, such as wars; and through particular means; such as memorialization. In a post-modern culture the past is made present through musealization; through new monuments, through public institutions, archives and museums that store and display heritage, but it is also accomplished by texts in print form and, increasingly, the electronic media. Canadian poets, novelists, historians, cultural critics, and the broader community of academics and journalists writing about history, memory and identity all contribute to the process of storing and altering memory, the process that both enables and complicates the study of any monument, particularly one as freighted with history and layered with significance as the Canadian National War Memorial. |

||||||

|

Notes

|

||||||

|

Sincere thanks to Gerry Killan, Eric Jarvis, Paul Werstine, Deborah Stuart, Lawrence Fric and Hunter Brown at King’s College for their time, support and assistance. The encouragement of two Moms—Pearl and Gerry, and the indulgence of two kids—Isabel and Charlie, was vital to this project. Most of all, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Holly Watson for her unfailing encouragement and support, critical insights and extraordinary patience, each of which was offered as needed, ‘above and beyond the call of duty!’ Finally, a special thanks to D.M.R. Bentley for his excellent guidance, painstaking editorial work and for making this project possible. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Works Cited and Consulted

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|