[3 blank pages]

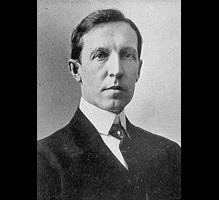

[unnumbered page; includes illustration: Philéas Bédard, folk-singer, Saint-Rémi de Napierville, Quebec]

FOLK-SONGS

of

OLD QUEBEC

by

Marius Barbeau

Song Translations By

REGINA LENORE SHOOLMAN

Illustrations By

ARTHUR LISMER

DEPARTMENT OF MINES

Hon. W. A. Gordon, Minster; Charles Camsell, Deputy Minister

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF CANADA

W. H. Collins, Acting Director

Anthropological Series No. 16 [unnumbered page]

[blank page]

CONTENTS

| Page | |

| Origin and varieties of Canadian folk-songs | 1 |

| How folk-songs travelled | 13 |

| The folk-songs | 28 |

| La Plainte du coureur des bois | 28 |

| Le Prince d’Orange | 31 |

| Le Prince Eugène | 34 |

| Le Retour du soldat | 37 |

| A la Claire fontaine | 40 |

| La Rose blanche | 42 |

| Dans les haubans | 44 |

| Le Miracle du nouveau-né | 46 |

| Rossignolet sauvage | 49 |

| Qui n’a pas d’amour | 51 |

| Là-haut sur ces montagnes | 54 |

| Dame Lombarde (seven melodies) | 56 |

| Renaud | 60 |

| Germine | 65 |

| La Nourrice du roi. | 69 |

| Bibliography of French Canadian folk-songs | 71 |

| [unnumbered page] |

[blank page]

FOLK-SONGS OF OLD QUEBEC

ORIGIN AND VARIETIES OF CANADIAN FOLK-SONGS

FOLK-SONGS were once a feature of the daily life of the French Canadians. They were as familiar as barley-bread to the home-keeping villagers of Quebec, Acadia, Detroit, and Louisiana. They escorted the fur traders in their early explorations across the continent, and enlivened the echoes whenever the lumberjacks and the raftsmen appeared on the eastern Canadian rivers. Threshing and winnowing in the barn moved on to the rhythm of work tunes, as did spinning, weaving, beating the wash, or rocking the cradle by the fireside. Children, lovers, mothers, workers, drinkers, all had their songs. People were musical in the old days.

When the coureurs des bois started on their long journeys along the rivers and the trails of the Far West, one or two hundred years ago, their outstanding qualities were imagination, endurance, a love of fun, and a craving for adventure. Picking up the paddle, the canoemen burst into song at once, the better to work in unison and keep their spirits from flagging. Their songs were truly indispensable. A legacy of the past, they proved a valuable asset to the discoverers and the fur trading companies for over two centuries, and contributed much to the formation of the national character of the French Canadians.

Not many song records antedating 1865 have come down to us, however. At that date, Ernest Gagnon published his Chansons populaires du Canada, a small but valuable collection. The idea then went abroad that his effort, modest though it was, had drained the fount of local tradition. More songs might have been recorded before they had passed away, but modern life had hushed all folk-singers alike. Tale and legend had vanished forever. The impression among the musicians was that our folk-songs, as represented in the Gagnon collection, were very limited in number and of no great musical importance.

The writer was under this false impression for many years, until some interesting survivals by the roadside piqued his [unnumbered page] curiosity. A systematic search during the summer months nearly twenty years ago opened wide vistas. There were still good folk-singers, and many of them. They possessed a treasure-house of songs, over a hundred songs to one singer alone—more than the whole Gagnon set itself. The tunes were fresh, rhythmic, and spirited, as if they had been sung for the first time. The panorama of ancient French life at the Court, in town, or on the country roads, was brought back into existence. The miracles and dark tragedies of mediæval times were retold as if they had happened yesterday. No survivial of the past could be more vital and inspiring. It seemed no longer possible that the traditions of a people could sink overnight into oblivion.

In the past fifteen years, over 6,700 versions of songs have been recorded by the writer and a few collaborators—Messrs. E.-Z. Massicotte, Adélard Lambert, A. Godbout, Gustave Lanctôt, and Father Arsenault. The songs were taken down in writing from various parts of Quebec, the Maritime Provinces, and New England, where Canadian emigrants are numerous; and about 4,000 melodies were recorded on the phonograph. In the same period, 3,000 records were made of Indian songs from all over the country.

The folk-singers were talented; their memory was prolific; their stock of songs was novel and inexhaustible. But they never gave free rein to improvisation, never ventured into new paths. They did not compose poems and melodies, but simply repeated what they had learned in childhood. That improvisation to their knowledge never happened was repeatedly confirmed. True enough, they spoke of some poets of the backwoods who could string rhymes and stanzas together on a given theme to suit local demand. But these were mere individuals, without mystic powers. They plodded over their tasks and matched their lines to a familiar tune. The result was uncouth and commonplace. There was nowhere a fresh source of inspiration, only imitation, crude and slavish.

It became obvious that a wide discrepancy existed between the actual facts and the theory of Grimm, still current in the English-speaking world, that folk-songs and perhaps tales are the fruit of collective inspiration. How puzzling it seemed when the Quebec singers were compared with American negroes [page 2] [page 3, includes illustration: Vincent Ferrier de Repentigny, folk-singer, Beauharnois and Montreal.] and Balkan peasants who are said to break into poetic outbursts when gathered together for group singing. If illiterate folk truly possess the gift of collective utterance, why not the Quebec singers as well as their forefathers or the Serbians or the negroes of the lower Mississippi? The writer has come to the conclusion that the theory of Grimm does not apply to Quebec, nor to France, where folk-singers do not create song, but only conserve and transmit them orally.

Tabulating the first collection of records and comparing them with those of provincial France made it clear that perhaps nineteen out of twenty Quebec songs were fairly ancient; they had come from overseas with the seventeenth century immigrants to enliven the new woodland homes. To this ancient patrimony new songs were added by rustic song-makers. These form the purely Canadian repertory, perhaps only ten per cent of the whole. All the others have come from France more or less in their present state. Some of them were composed during the last three centuries and brought into Canada in the form of broadsheets and books of canticles. Others, more recent, are truly in the folk-song vein; they are marching and college songs brought over orally after 1680 by soldiers, priests, and teachers.

Then we come to the bulk of the repertory—the true folk-songs, those of the early immigrants of New France—between 1608 and 1673.

Thus we find three classes of songs: the genuine folk-songs of old France, those introduced here since 1680 and mostly composed or transmitted by way of writing, and, lastly, the true songs of French Canada.

The singers themselves could give little information as to the origin of their heirlooms. Only a few of the most recent songs – election and political ditties and mournful songs on drownings and tragic deaths – could be traced back to their source. It was the singers’ habit to rehearse what had come down to them from the dim past. A composition five centuries old was sung next to another dating back two generations. Some Gaspe fisher-folk would call the age-worn complainte of “The Tragic Home-coming” by the name of Poirier—La chanson de Poirier. Poirier was still remembered by the elders, as if he were its author. Others claimed that the canticle of “Alexis” [page 4] was as much as a hundred years old, when it was more nearly a thousand. The singers’ notions of origin were not worth serious consideration.

If the melody in these songs of the land is usually superior to the words, it is because these melodies are derived from good prototypes, and the rustic bards to whom we owe them were better versed in melody than in lyrics. Talent and the familiar knowledge of many tunes were fair musical guides. Rhythm and tune are more elemental than grammar and verse; they are nearer nature. A good instance is La Plainte du coureur des bois. Musicians are likely to respond to its moving appeal. But the lines, stripped of their melody, will not be mistaken for good poetry.

LA PLAINTE DU COUREUR DES BOIS (Page 28)

Tunes are more fluid than song texts. They can easily be altered without an irreparable loss. Several variants of a melody may be equally good; it is not usually possible to tell which is closer to the original. But a poetic word cluster once lost is irretrievable. A scar takes its place, with words casually thrown in by the singers to hold up the tune. Such lacunæ—some of them quite old—disfigure many of our best records.

In the past three hundred years, the ancient French tunes in Canada have undergone marked changes. They do not always resemble closely their French equivalents. Parallels, indeed, are the rare exception, particularly in the old songs; this is partly due to the paucity of French records for comparison. The same words may be sung to several tunes, according to their use. Few of these tunes, on both sides of the Atlantic, correspond, though the poems are much alike, despite variations.

Because of this melodic fluidity, the tunes in our repertory are more Canadian than the words; their local colour is pronounced, yet they retain a mediæval flavour. Whatever gradual changes happened, the character and technique remained largely the same as at the beginning. Singing in the remote districts of Quebec, like Charlevoix and Gaspe, is more archaic than elsewhere, as a result of prolonged isolation and ingrained conservatism. [page 5]

The distinction between the newer and older French songs in Canada was not very clear. The elimination of some was necessary, for the songs, particularly at points within easy reach of a town, were not all of folk extraction. A singer’s repertory was like a curiosity shop; trifles and recent importations vied with old-time relics.

The French “romances” of 1820-40 were once the fashion. Not a few of them, like the satires on Bonaparte, had somehow found their way into America, in print or otherwise, and filtered down into the older strata of local lore, where they still persist long after their demise in the homeland. Many songs passed from mouth to mouth until they no longer remained the exclusive favourites of school and barracks, and country folk were on the lookout for just such novelties.

Compilations printed in Canada and ballad sheets imported from France (imageries d’Epinal et de Metz) spread their influence to many quarters. Among the additions from this latter source we count Pyrame et Thisbé, on an old Greek theme, Damon et Henriette, a mediæval story, Cartouche et Mandrin et Le Juif errant (the Wandering Jew). The length of these exceeds that of ordinary folk-songs. They also have a literary turn in the manner of Aucassin et Nicolette. Pyrame and Damon both consist of more than two hundred lines, whereas ordinary folk-songs seldom pass beyond forty or fifty.

The ancient canticle of Alexis occurs in two forms: the first, out of the Cantiques de Marseille, the oldest song-book in canada—well before 1800; and the second from hitherto unrecorded sources of the past. Under its literary form it goes back to the tenth or eleventh century; it is the first known religious song in the French language—lingua vulgaris—at its very birth as a written and church language.

The true folk-songs arrived in Canada before 1680 with the early settlers from the provinces of Normandy and the Loire river. These songs far exceed all others, and they are incomparably the best. Their style is pure and crisp, their themes clear-cut and tersely developed. Their prosody differs widely from that of the troubadours and from literary French. Grace and refinement prevail throughout, and in some there are flashes of genius. Here is decidedly not the work of untutored peasants, [page 6] nor a growth due to chance, but the creation of poets whose consummate art had inherited an ample stock of metric patterns and a wealth of ancient lore common to many European races.

Our best folk-songs are not a direct legacy from the troubadours, for troubadour songs were written on parchment for the privilege of the nobility; they belonged to the aristocracy and [illustration: Mme. Jean-Baptiste Leblond, spinning and singing folk-songs, Sainte-Famille, Island of Orleans] the learned, not to the common people. They affected the finesse, the philosophy and literary mannerisms of the Latin decadence; and they were composed in the Limousin and Provencal dialects of oc, in southeastern France. The troubadours themselves wrote their songs between the eleventh and the fourteenth centuries, whereas many of the best folk-songs belong to the two hundred years that followed. Our songs could not be translations into oïl of compositions originally in an oc dialect. The spirit, the technique, and the themes of the troubadour poems [page 7] have little or nothing in common with those of our songs. Here we are dealing with two worlds apart: the one, the high Latin tradition, and the other, the earlier influx of southern culture through folk channels, after the Roman conquest.

On the other hand, there were the jongleurs errants and jongleurs de foire of ancient times, whose pranks were derided in the manuscripts of the troubadours and the minstrels. The jongleurs were the butt of society. As they did not use writing, no evidence is left to vindicate their memory. But students of mediæval literature have pointed out that while the troubadours had their day in the south, an obscure literary upheaval, free from Latin influence, took place in the provinces of the Loire river and the north—exactly in the home of our traditional lore. Who were the local poets if not the jongleurs themselves? What were their songs if not those that have survived and come down to us through the unbroken oral tradition of the same provinces?

Whatever those Loire River bards be called, they were by no means devoid of culture. At their best they composed songs that not only courted the popular fancy but which, because of their vitality and charm, outlived the forms of academic poetry. Besides, their independent prosodic resources were not only copious, but they went back to the bedrock of the Gallo-roman languages. Unlike the troubadours who belonged to the lineage of mediæval Latinity, those northern poets had never given their allegiance to a foreign language since the birth, before the fifth century of Christianity, of the Low Latin vernaculars, in France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. They had inherited and conserved the older traditions of the land. Presumably they were the heirs of the ancient Druids and the Celtic culture that had undergone a mutation without altogether going out of existence.

In other words, the folk-songs of France as recovered in America—more numerous and better preserved than at home—mostly represent an ancient stratum of French literature, one which despite discredit was never wholly submerged by the influx of Neo-Latin influences from the south.

But the jongleur art went out of existence in France itself before the dawn of the seventeenth century, with the appearance of printing and broadsheets. If we have true folk-songs of the sixteenth century—those of Le Prince d’Orange and Le Prince [page 8] Eugène—it seems that later compositions are in the literary style that belongs to writing. At least, not one of the early settlers was endowed with the jongleur tradition, for we lack any historic reference to the art or any native song disclosing the presence of jongleur traditions in the New World. The troubadours died out in the fourteenth century; the jongleurs seem to have fanished in the sixteenth.

LE PRINCE D’ORANGE (Page 31)

LE PRINCE EUGÈNE (Page 34)

The old repertory of folk-songs is quite varied. It does not consist, like that of the Mediterranean border, of lyric songs exclusively, nor of narratives and ballads, like that of Scandinavia. But it is mixed, both types being generously represented.

The ballads and narratives of the North sea belong to Normandy and northern France. Some of them slipped across the oïl frontier in central France into the southern provinces; some few passed the mountains into Spain and northern Italy—“Le Roi Renaud,” for instance. The lyric songs thrived in southern France and on the Loire river, and invaded Normandy at an early date. In spite of this ready interchange, ballads in France remain northern to this day, whereas the lyric poem is typical in the provinces to the south. This is the outcome of ancient classic culture, more philosophic and abstract in its trends, more firmly rooted in southern France than in the north. This contrast between northern and southern France assumed particular significance when it was found that the eastern districts of Quebec had far more ballads and complaintes (come-all-ye’s) than those of Montreal, to the southwest. Quebec proper is predominantly Norman, whereas Montreal owes more to the Loire river. The earliest immigrants after 1608 and 1634 embarked for New France at Honfleur, Havre, and St. Malo, on the British channel, and settled in the neighbourhood of Quebec. Many of the others, after 1642, sailed from La Rochelle, on the Atlantic, and proceeded to the upper river settlements of Three Rivers and Montreal. This diversity of origin has left many traces to this day. The singers of Charlevoix and Gaspe to the northeast differ from the others; they are the Canadian Normans. Their songs have an archaic tang, and [page 9] [page 10, includes illustration: François Saint-Laurent and Joseph Ouellet, fishermen and folk-singers, La Tourelle, Gaspe.] lean by preference towards the narrative type. An instance, though not very ancient, is that of “The Return of the Soldier Husband”, also familiar in Great Britain through Tennyson’s Enoch Arden.

LE RETOUR DU SOLDAT (Page 37)

French folk-songs, particularly as preserved in Canada, have some points in common with those of England, and this is only natural. A good many of them are practically the same, except for the idiom. Centuries after the Normans had conquered the island, the British for many years ruled over northern France, even Aquitaine to the southwest. Some geographic names in Normandy (such as Dieppe=Deep) are English, whereas many more in England are French. Were it not for the rise of Joan of Arc, both France and England might have been joined together under the same Norman crown. The songs of one nation would have been those of the other, for many were common possessions in those days of unborn nationality.

Canadian songs like those of north and central France were applied to almost every phase of daily life. There were cradle and wonder songs, play-parties and round dances—for the nursery; love songs of every conceivable type—many of them quite gay; dialogues and vaudevilles; a large number of anecdotal and comic songs; rigmaroles; work and dance songs; and, in the religious vein, Christmas carols, miracles, and folk canticles.

Foremost was the working song with its invigorating rhythm, intended to sustain the energy of the toilers. It is the best known at large. It was used by canoemen, wood-cutters, and ploughmen; and again, fullers, spinners, and weavers. Typical among these songs are A la Claire fontaine (page 40), Le Plongeur et la bague d’or, Le Fils du roi s’en va chassant, La Fille du roi d’Espagne, La Rose blanche (page 42), and Dans les haubans (page 44). Le Miracle du nouveau-né (page 46), which follows, is not so well known, nor is it a characteristic work song as it combines elements that belong both to the canticle—it relates a miracle—and to the work song: a refrain of short lines (eight beats, cut in two by the cæsura), and fair rhythm. The rhymes are consistently masculine, as in ancient poetry. [page 11]

A LA CLAIRE FONTAINE (Page 40)

LA ROSE BLANCHE (Page 42)

DANS LES HAUBANS (Page 44)

LE MIRACLE DU NOUVEAU-NÉ (Page 46)

Among the numerous love songs of varied age and description, three or four types may be singled out as ancient and typically French: the shepherd song, the rossignol messager (nightingale messenger of love), the aubades, and nocturnes. Although they rest upon short narratives, their intention is lyrical. They are mediæval, perhaps largely from central France, and they embody some of the finest melodies we know.

Though not of troubadour origin, their themes were far from unfamiliar in southern France; they were also used in the written literature of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. These lyric songs underwent a peculiar evolution in the course of their long history. Like many other songs of the Middle Ages they spread from France to neighbouring countries.

ROSSIGNOLET SAUVAGE (Page 49)

QUI N’A PAS D’AMOUR (Page 51)

LÀ-HAUT, SUR CES MONTAGNES (Page 54)

[page 12]

HOW FOLK-SONGS TRAVELLED

What characterizes ancient folk-songs is their inveterate nomadism. Born under the stars as it were, they at once took to the road or the sea. Their life was like that of the Wandering Jew of the mediæval legend and song. Aged and usually ragged, they knew of no harbour of grace. Impelled by a fate that goes back to their oral birth and transmission, far away and long ago, they had to keep on travelling, for as soon as they stopped, they died. No frontier impeded their progress for very long; they knew how to change garments and penetrate everywhere; they passed into other languages, hid their origin, and were sung by the country folk.

To the songs of all of Europe was one country, which they criss-crossed in all directions. Often they embarked on ships and sailed the seas, landing at many ports, even in America.

Striking instances of how folk-songs have travelled down the centuries and over the map will bring out this characteristic; the more so since we shall pick them where we found them—far from their birthplace, among the vast number of French Canadian folk-songs recorded in recent years on the shores of the St. Lawrence.

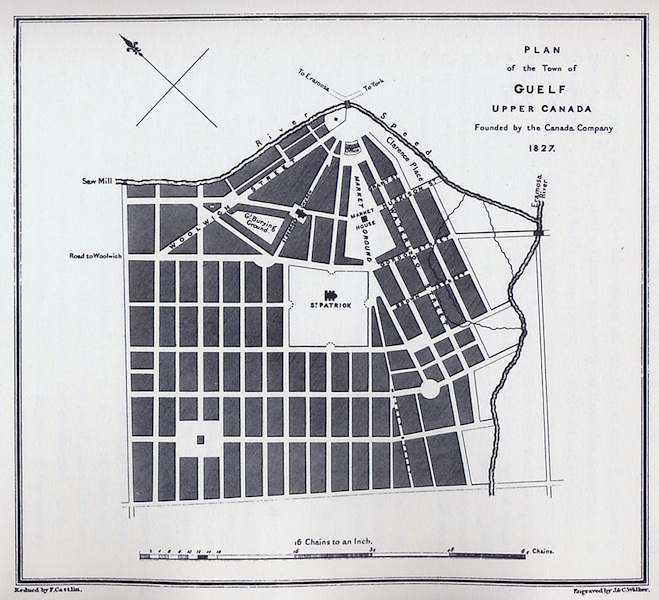

One of these songs is Dame Lombarde: it had its inception in northern Italy, at the end of the sixth century, assumed its fixed form a century or two later, migrated into France, where it was recorded only once (on the Italian frontier), and finally passed to French Canada, where it has survived to this day. A second instance is Renaud: it came to life in Scandinavia, where it is still familiar, crossed the North sea into Germany and Brittany, passed from Celtic Brittany to France proper, and thence travelled in all directions on the continent. A third song, Germine, is a reminiscence in southern France of the Crusades; it invaded northern France, Brittany, and several Mediterranean countries. And fourth, La Nourrice du roi (The King’s Nurse-maid), is a religious song of Spain, which passed the Pyrenees and settled in France, close to the Swiss frontier. These songs emigrated from France and crossed the Atlantic in the seventeenth century; they are still popular at large among [page 13] [page 14, includes illustration: Vincent-Ferrier de Repentigny and Philéas Bédard singing the song “Mon père, je voudrais me marier”.] the country folk of French Canada. The melodies were recorded on the phonograph, and transcribed; and the words written down from dictation, in many versions, at scattered points from Ottawa river down to the Acadian settlements of Nova Scotia.

DAME LOMBARDE (Page 56)

This complainte is unique in the folk-song repertory of French Canada. It came to the St. Lawrence, through France, from the south, from Italy, upstream as it were, not down, as is usual for narrative songs: the complaintes belong to the north, and they travel southwards, whereas the reverse is true of lyric songs.

This song is also one of the most ancient in our repertory, in historic contents at least. It tells the story of Dame Lombarde, the tragic Rosmonde, who tried to poison her husband at Ravenna in the year 573, but was forced to drink death from the cup she herself had filled with wine and with fluid from the crushed head of a serpent.

The discovery of Dame Lombarde’s identity as the principal character in the song is to be credited to Nigra, the Italian traditionist. For several centuries after the event, this ancient story of poisoning was the object of chronicles. George Doncieux (Romancéro, 174-204) recently linked it up with the only French record so far discovered, near the Italian frontier, in the French Alps.

Alboin, the king of the Lombard invaders of northern Italy, incurred the hatred of Rosmonde, his wife, when he forced her to drink from her father’s empty skull. Bent upon revenge, she seduced Helmichis, an officer, and compelled him to yield to her will. He killed Alboin, his king, and became her second husband. She tried to govern the country, but the Lombards rebelled and forced her to flee at night with Helmichis. At Ravenna she was well received by Longin, a prefect of the town. To regain the crown she had lost, Rosmonde decided to rid herself of Helmichis, who now stood in her way. Once more she used her charms and won Longin to her ambition. He begged her to regain her freedom and marry him, so as to reign over the Lombards again. [page 15]

This time she resorted to poison. The chronicler, Agnellus of Ravenna, relates how Helmichis, coming out of a steaming bath, received from Rosmonde a “cup filled with a beverage, seemingly to quench his thirst, but really meant to poison him. No sooner had he drunk death from the cup than he tended it to the queen, saying, ‘You too drink of it!’ She refused; he drew his sword and, threatening her, said, ‘If you don’t, I stab you!’ She drank, and both died instantly.”

Paul Diacre and Agnellus, Lombard chroniclers of the eighth century, both recorded the adventures of Rosmonde. The story from the pen of Agnellus resembles our song so closely that nigra considers them identical. Dame Lombarde is no other than Rosmonde. The Italian complainte would be contemporaneous with the event, as songs are born out of real life; they are not derived from parchment and ancient chronicles. In this Nigra is undoubtedly right.

But Doncieux does not accept this theory. The Italian versions of the songs end with a slur upon the “King of France”, who is said to be the seducer of Dame Lombarde. François I, Doncieux thinks, is the King; his gallantries were notorious, and he was at Pavia, Italy, with his army, in 1525. Dame Lombarde cries out, “For the love of the King of France I die!” And this line alone, according to Doncieux, gives a date to the whole song, which, for other reasons as well, could not go back to so remote a date as the sixth or the eighth century.

Who is right, Nigra or Doncieux? Does the song go back to the eighth century or the sixteenth? The point is of interest, since it bears on the age of folk-songs generally—very old or comparatively recent. The issue here might remain in doubt, were it not for our French-Canadian records, which were not known to the Italian and the French traditionists.

Our nineteen versions of the complainte “Enseignez-moi donc!” (Oh! teach me!) from the lower St. Lawrence throw a new light on the ultimate origin of Dame Lombarde, for they are one and the same. The Canadian records begin in two different ways: a wife is advised to poison her jealous husband by a neighbour, in some versions, and by a bird, the nightingale, in others. Wide variations are also found in our records, both in words and melodies. Two branches of the French song independently [page 16] crossed the sea with the early settlers; one of these took root on the Atlantic coast with the Acadians, and the other up the St. Lawrence in the neighbourhood of Quebec. That the song at the time of its migration into America was already old and decadent, is obvious. It clearly belongs to a stock older than “Le Prince Eugène,” “The Three Poisoned Roses”, and “The Prince of Orange”, which are sixteenth century songs. The melody (No. 1, Dorion) from Acadia is different from those of Quebec, which are quite varied.

The song of Dame Lombarde must have sojourned in northern France—Normandy and the Loire river—for generations before its versions became diversified as they were at the time of their exodus to Canada, in the seventeenth century. Its origin long antedates François I, whose reign coincides with the discovery of the New World. For, in so little time, less than a century, it could not become popular in northern Italy, cross the Alps, spread to southern French (langue d’oc), invade the dialects of oïl, in northern France, and then, already divided in two and widely assimilated, sail the seas to the St. Lawrence. Were that possible, it is unlikely that historical facts as recent and well known would have been so utterly distorted. François I could not have known the legendary Dame Lombarde of the complainte, still less figure with her in a notorious poison affair long since forgotten outside of the already existing song.

The last line of the Italian versions “For the love of the King of France I die” is a belated alteration, an afterthought prompted by subsequent events, as often happens in folk-songs. It may not even be contemporaneous with François I, as other kings of France before him had entered Italy.

Doncieux’ knowledge of the French distribution of Dame Lombarde was insufficient; the Canadian versions had not yet been collected, nor the three variants since discovered by Millien (Chants et Chansons … Nivernais, I, 94-97) in northern France. His excuse to include the Italian complainte in his Romancéro was the only southern French version found in the Alps; and the text, which he gives first, is a translation from the Italian.

Our Canadian song does not allude to the French king; it concludes with the words: “Cursed be the neighbour who taught me …!” or “the nightingale…” In this it stands [page 17] [page 18, includes illustration: Saint-Hilarion, Charlevoix.] closer than the Italian records to the ancient story of Rosmonde which seems to have crossed the mountains northwards and taken root in all of France at an early date. Otherwise it would not have crossed the seas, as it did with the colonists from Normandy and the Loire nearly three hundred years ago.

RENAUD (Page 60)

The complainte of Roi Renaud is perhaps the most famous of all the French folk-songs. Its history, like that of Dame Lombarde, is remarkable, if not unique. After its obscure birth in Scandinavia, at the end of the Middle Ages, it spread to the northern coasts, landed in Brittany and Germany, and then passed to all of France. From there, it leaped the frontiers into Italy and Spain. it crossed the ocean westward with the settlers of New France, in the seventeenth century. It is deeply rooted on the lower St. Lawrence and in Acadia.

Lost sight of in the lore of several countries, it might have disappeared forever like many others, but it was discovered and revived at the end of the last century among savants and artists, and then for the benefit of the public in general. Fascinated by its unusual features, folk-lorists studied it quite thoroughly, and a great artist, Yvette Guilbert, conferred fame upon it on more than one continent. It is a masterpiece that has won universal recognition, particularly in its French form.

The song of Renaud already had a long past behind it when it embarked for Quebec and Louisburg with the ancient settlers. Since then it has been preserved in obscurity, by many generations of uneducated folk-singers. It is one of the best known of the traditional repertory, but only on the lower St. Lawrence; it does not seem to have ascended the river far beyond the old town of Quebec.

As late as 1917 it had not been discovered in Canada, where the study of traditions until then had been much neglected. Yet the song had survived, if only among country folk whose recollections are anchored deep in the past. It is still sung in the winter evenings in the semi-Norman districts of L’islet, Kamouraska, and Temiscouata; more frequently still in Gaspe and around Chaleur bay. Its features have been faithfully preserved, in spite of long peregrinations. The variations in themselves often [page 19] have an interesting significance, as, for instance, the beginning of a Jersey version recorded on Chaleur bay: “Good news, O my King Louis: Your wife has given birth to a son.” Renaud had thus changed to Louis, to suit other times, already remote.

Scholars discovered this song in Europe a decade or two before 1850. De la Villemarqué published a Breton fragment in his Barzaz Breiz in 1839. Gérard de Nerval twice inserted it in his books. Since then it has been the object of numerous studies; Ampère, Rolland, Bladé, and other French traditionists collected many versions, and swelled its bibliography. Writers meanwhile studied its roots in Scandinavia, and followed its development through France, Spain, and Italy.

Doncieux recently compiled those scattered data for an impressive mongraph in his Romancéro (VII, 84-124). He derives his final text from fifty-nine versions from France and eight from Piemont (Italy); and he mentions that it was sung in Paris when Henry IV entered it, in 1594; also in Brittany, in the second third of the sixteenth century.

The number of French versions has since grown by at least thirty. Millien has published five main variants for Nivernais (France), and he quotes other sub-variants; Rossat has brought out three versions in Switzerland (Suisse romande); and our Canadian collection includes twenty-two versions. In all, there are about ninety French records.

This is only a fraction of the grand European total, since the Latin countries alone contain five songs closely related to Renaud: an Armorican gwerz, a Basque song, a Venetian canzone, a Catalan song, and a Spanish romance familiar in all the peninsula. This group alone, exclusive of France proper, is represented by sixty-seven songs.

The song is still more important in the Scandinavian countries, where it found its birth: the vise of the Knight Olaf, which is one of the finest and best known in the north. Gruntvig compiled sixty-nine versions for Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Faroe island. The oldest written record, from Denmark, dates back to 1550.

The total list of versions is large: 90 French versions; 67 from the other Latin countries; 69 Scandinavian records. In all, 226. And there may be still more. [page 20]

The Scandinavian song is said to have originated in Denmark, where it was first recorded in writing, before the middle of the sixteenth century.

A folk theme widely familiar in the Germanic countries long ago, was embodied in a poem, on the Rhine; that of the “Knight of Staufenberg,” which was known in Scandinavia and gave birth to the folk-song. This song travelled widely and grew into three branches: a Scottish ballad, a Slavonic song, and a gwerz in Celtic Brittany. The French song originated from the gwerz and developed into several adaptations: Basque, Venetian, Catalan, and Hispano-Portuguese.

The nine songs of this series, in as many languages, are not all of the same importance, according to Doncieux. Six of them follow the Scandinavian or the French forms closely, when they are not awkward adaptations. But three of them are authentic compositions with distinct individuality: “Sire Olaf”, “The Count Nann”, and “Renaud”. Linked as they are through descent from the same theme, they constitute a lineage of masterpieces in traditional literature that may be considered unique. They bear equally the stamp of creative genius. If a Dane first used the folk theme, a Breton transferred it to a gwerz, and a Frenchman of genius made of it a song that is hardly surpassed anywhere for power and beauty.

The encounter of the knight with a fairy is the outstanding feature of the Danish song. To the folk theme the poet adds the flight on horseback at dawn, which he drew from his powerful imagination, the dance of the elves on the hillside, and the invitation to join in when the fairy shows her passion for the knight. The vivid charm of this scene wherein legend and truth mingle, belongs wholly to Scandinavia; it is hardly transposed into the Breton song; it is not even hinted at in the French. The plot in the Danish vise moves on rhythmically, with growing anguish and terror, from the moment when the knight meets the fairy to that of his death, after he arrived home. The fiancée’s three questions about the sound of the bells, the women weeping, and the absence of her beloved, are included by undeveloped. The Breton gwerz and the French complainte alone make full use of them. [page 21]

The dialogue on the secret death of the absent, only vestigial in the Scandinavian song, is enlarged upon in the Breton gwerz to the point of becoming the central theme. Here the knight was not proceeding to the home of his virginal fiancée, but to his own, where his wife had given birth to a son. Fantastic and dreamy, the Scandinavian story here becomes realistic and intensely dramatic. The French song omits the episode of the elves and the fairy, and consists almost wholly of a dialogue between the knight’s mother and his wife. It confers upon the story fresh beauty and inspiration. Its master strokes reach the sublime. The wife, discovering the terrible truth, dies of a broken heart and is buried with her husband.

“Renaud” closely resembles “The Count Nann”, its Breton parent. It differs in one point—unity—which makes it perhaps the best of the three songs. The gwerz is made of two separate themes, that of the fairy and of the secret death, which are consecutive. Thus it is divided in two halves, one legendary, the other actual and poignantly human. Lack of unity is its only fault. But all that is exotic is swept aside in the French song, which begins with the tragedy of the knight arriving home to meet his mother on the threshold. He dies in her arms, and the dialogue between the mother and the wife forms the whole drama. Narrative verse, introduced here and there, enhances the intensity of the plot and hastens it to a climax—the funeral bells, the tomb, and the oath at an open grave.

GERMINE (Page 65)

The splendid complainte of Germine or Germaine takes us back to the Middle Ages. It is a lyrical reminiscence of the Crusades.

The Crusader returning home here is ostensibly the Prince of Ambroise, or better still, Guilhem de Beauvoir, who sailed the seas, and was absent for a long time, while his young wife met with adversity and remained true to her pledge of fidelity.

The song begins at the moment when the Crusader arrives home. The scene opens with a dialogue. After so many years the Crusader is not recognized. He has to plead for hospitality. Before Germine will believe him, he must furnish proofs, and there lies the plot, and its intense dramatization. [page 22] [page 23, includes illustration: Road to the school near Baie-Saint-Paul, Charlevoix.]

Its treatment insistently resembles that of Renaud. Their inception must be related in some way. One perhaps was known to the composer of the other, and Germine presumably was the first.

Both themes are epic: their birth goes back to ancient legends and traditions. In Renaud, a knight comes back home with a wound, to die on the threshold before his wife has seen him; in Germine, he is recognized at last and the years of waiting and trial are over. There ends the resemblance of the story. But the treatment is the same. The poet dramatizes his story, unfolds it in a few strokes and swiftly proceeds to the end, one fatal, the other blissful. Here we find in brief form and in simple though transcendant melodies, two of the finest creations of the French genius, now weather-beaten and broken with age, but still magnificent in their decay. They resemble cathedrals gnawed by the winds and the rains; in the shadow of these ancient temples they were born in the years long since forgotten.

The “Return of the Crusader” became a literary theme at the time of the Crusades, the last of which took place in the thirteenth century. Very early it was sundered into two folk-songs which have come down to us: La Porcheronne (The Swineherd) and Germine.

Their story is fundamentally the same, but the form is different. “The Swineherd” originated in southern France, whereas Germine is from north of the Loire. In their long independent careers they travelled widely, sometimes side by side, often sojourning under the same roof.

Germine seems better known in French Canada than in France, whereas in France “The Swineherd” is more familiar. Seventeen versions of Germine were recently recorded along the St. Lawrence and in Acadia. “The Swineherd” has hardly survived in Canada, where the writer recovered only two fragments, one in Temiscouata and the other in Gaspe. The Crusader, in Canada, bears the name of “The Arabian” (l’Arabe), which comes from his peregrinations in Moslem countries.

The contrast between the two is marked. In Germine, the young wife awaits her long-absent husband in her castle. Surrounded by her maids, she refuses to open the door, even to [page 24] the knight who claims to be the most handsome in the land. She is a grand lady, haughty and respected. But the Swineherd undergoes more severe trials than Germine, in her long abstinence. Her husband’s mother persecutes her and degrades her to the rank of a serf keeping herds in the fields, where she weeps for sorrow.

“The Swineherd” originated in southern France, according to Doncieux; more precisely, in Provence, near Beauvoir-de-Marc (Isère). From there it spread to all of France, to Catalogna (Spain), where it is familiar, and to Pimont (Italy). It crossed the ocean into New France, in the seventeenth century, but never developed on this side.

The Crusader of the song seems to be Guilhem de Beauvoir, an historical figure of the thirteenth century, one of the most powerful barons of Dauphiné. Beauvoir’s long adventures abroad ended after his return home, and he died leaving his will dated 1277.

Which of the two songs, “The Swineherd” or Germine is the older, no one can tell. Perhaps it is “The Swineherd”. The home of this song is nearer its birthplace, and the story follows closely the historical facts that seem to have inspired the composition. The verses are better preserved than those of Germine, which are in an advanced state of decay, and there are traces of a southern origin in Germine. In some of the versions, the Crusader is named Beauvoir, or Beaucère—from Beauvoir, in “The Swineherd”. And a town mentioned is Lyon (“Mes chiens de Lyon” and “Le pont de Lyon”).

“The Swineherd” is quite different from Germine in treatment. It is episodic, and relates several episodes of a long adventure. Germine holds only one, which it vitalizes and transfigures. One is legend or history, the other is art, and a masterpiece.

These songs after their birth, one in the south and the other in the northwest, travelled the whole country, even crossed the frontiers and the seas, and halted only on our very doorstep. The seventeen Canadian versions of Germine were recorded on the St. Lawrence from Montreal down to Chaleur bay; they belong mostly to the districts where the settlers are predominantly Norman. One version was found among the Acadians of [page 25] Prince Edward Island. It is not so well remembered in France. “The Swineherd” was more popular there, although it cannot have been familiar to many of the northern colonists who settled in the New World; otherwise it would have survived here more than it has, in scattered fragments.

Only a few records of Germine can be found in the published collections of France, mostly from the northern provinces and perhaps without the melody, whereas thirteen versions of “The Swineherd” are listed by Doncieux.

The occurence of these two songs outside of France proper is quite extensive. “The Swineherd” was first published by de la Villemarqué for Celtic Brittany in 1839 (Barzaz Breiz, XIX). And de Puymaigre, who first discovered Germine, compared it to Don Guillermo of Catalogna (Spain). He indicated its distribution in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, Bohemia, Germany, Holland, Flanders, and England.

Crane, in his Chansons populaires de France (267-8), connects it with “Hind Horn” and “The Lass of Loch Royal” published by Child (The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, 213, 111, 187). And Nigra (Canti popolari del Piemonte) shows how this southern French song spread to Spain and Italy, and from there invaded Greece and even the Slavonic countries.

It is also possible that it may go back to an earlier date than the last Crusade. De la Villemarqué believes that it originated in Brittany after the first Crusade, in the eleventh century, and that it dramatizes the return of Alain, one of the Breton chiefs who spent five years in Palestine. If that were true, a Breton gwerz would be at the root of all that poetic growth, which later spread to all of Europe by way of France and Italy.

LA NOURRICE DU ROI (Page 69)

The only Canadian version of this folk canticle was found among the Acadians of Prince Edward Island, in the Maritimes. The eight or ten versions recorded in France belong mostly to the central provinces, the east and the southeast. As they are all much the same, their common origin is not very ancient. The song is a few hundred years old.

Before its migration to America, presumably with the early settlers, it had already travelled in Europe and become ramified. [page 26] The Acadian refrain differs from most of the French versions, but a Provencal form closely resembles the Canadian. There are also other differences. This nursery song, according to Doncieux, was composed in French proper, probably in the neighbourhood of Saint-Nicolas-du-Port, where Saint Nicholas is the popular patron saint.

In the local tradition, however, no trace can be found of this miracle of the saint, but a well-known song of Catalogna (Spain) contains a similar miracle which, there, is attributed to the Virgin, not Nicholas. If one of the two songs issued from the other, as is likely, the Spanish version probably is the original. Its details seem more authentic and the plot more logical. Catalogna, besides, has a sanctuary of Notre Dame, which is famous in all Christendom: the abbey of Montserrat, near Barcelona, where a black Virgin holding the Infant jesus has drawn, since the thirteenth century, many pilgrims from everywhere. The Catalan canticle must have originated here and spread to other parts with the pilgrims.

A French visitor is likely to have introduced it at Saint-Nicolas-du-Port, after returning from Montserrat. Then it was adapted to the worship of the patron saint of the locality without robbing the Virgin of her credit: Saint Nicholas is only a party to the miracle. Other instances of such miracles attributed to various saints are familiar elsewhere. The fame of miraculous shrines travelled far and wide, like the folk-songs of other days. [page 27]

THE FOLK-SONGS

LA PLAINTE DU COUREUR DES BOIS

[sheet music]

1 Le six de mai, l’année dernièr’,

Là-haut je me suis engagé; (bis)

Pour y faire un long voyage,

Aller aux pays hauts,

Parmi tous les sauvages. [page 28]

Ah! que l’hiver est long,

Que ce temps est ennuyant!

Nuit et jour mon cœur soupire,

De voir venir le doux printemps,

Le beau et doux printemps,

Car c’est lui qui console

Les malheureux amants

Avec leurs amours folles.

2 Quand le printemps est arrivé,

Les vents d’avril soufflent dans nos voiles

Pour revenir dans mon pays.

Au coin de Saint-Sulpice,

J’irai saluer m’amie,

Qui est la plus jolie.

Qui en a fait la chanson?

C’est un jeune garçon,

S’en allant à la voile,

La chantant tout au long.

Elle est bien véritable.

Adieu, tous les sauvages,

Adieu, les pays hauts,

Adieu, les grand’s misères!

Translation

1 The sixth of May, a year ago,

It was that day that I went away (bis)

On a long and distant voyage,

To lands beyond the bay

Where the woodland people stay.

O how long is the Winter!

O how slowly time passes by!

Night and day my heart does sigh,

Longing for the sweet Spring-time,

The sweet and lovely Spring!

For ’tis the Spring who will bring

Joy to fond lovers pining

For tenderness and cherishing. [page 29]

2 When Spring at last has come to stay,

The winds in our sails are gay.

Now I shall see my country-side

At Saint-Sulpice far away.

There I shall greet my bride,

Who is the loveliest maid.

Who sings this plaintive song?

’Tis a lad that is young,

Far away from his home land,

Singing it as he walks along,

Chanting the gay refrain:

Farewell, all you savage people!

Farewell, you rocky shores!

Farewell, all misery, all pain! [page 30]

LE PRINCE D’ORANGE

[sheet music]

1 C’était le prince d’Orange,

Là!

C’était le prince d’Orange. Grand matin s’est levé,

Madondaine,

Grand matin s’est levé,

Madondé.

2 A appelé son page: Mon âne est-il bridé?

Madondaine…

3 —Ah! oui, vraiment, beau prince! il est bridé, sellé!

4 Mit sa main sur la bride, le pied dans l’étrier.

5 A parti le dimanche, le lundi fut blessé.

6 Reçut trois coups de lance qu’un Anglais a donnés.

7 En eut un dans la jambe et deux dans le côté.

8 Faut amener le prêtre: je n’ai jamais péché!

10 Jamais n’embrass’ les filles hors qu’à leur volonté;

11 Qu’une petit’ brunette, encor j’ai bien payé,

12 Donné cinq cents liards, autant de sous marqués. [page 31]

Translation

1 It was the Prince of Orange,

Hey!

The gallant Prince of Orange.

Who rose at break of day,

O hey! Sing hey!

Who rose at break of day,

Hark-away!

2 He beckoned to his page,

Hey!

He beckoned to his page,

“O will you saddle my bay?”

O hey! Sing hey!

“O will you saddle my bay?”

Hark-away!

3 Already he is saddled,

Hey!

Already he is saddled,

And he begins to neigh.

O hey! Sing hey!

And he begins to neigh.

Hark-away!

4 Upon the bridle, his hand,

O Hey!

Upon the bridle, his hand.

His feet in the stirrup stand,

O hey! Sing hey!

His feet in the stirrup stand,

Hark-away!

5 He rode away on Sunday,

O Hey! …

And was wounded next day, …

6 An English lance waylaid,

O Hey! …

And gave him mortal blows, … [page 32]

7 A blow his foot did strike,

O Hey! …

Two blows his side alike …

8 A priest to him was brought,

O Hey! …

The last time he has fought …

9 “No need of priest have I,

O Hey! …

I never sinned, not I.”

10 “No girl have I ever kissed,

O Hey! …

Save when she did insist!

11 “Except a little brown maid,

O Hey! …

To her a good sum I paid …

12 Five hundred pounds I gave,

O Hey! …

Those pounds I might have saved!” [page 33]

LE PRINCE EUGÈNE

[sheet music]

1 Un jour, le prince Eugène, étant dedans Pari,

S’en fut conduir’ trois dames,

Vive l’amour!

tout droit à leur logis,

Vive la fleur de lis!

2 S’en fut conduir’ trois dames tout droit à leur logis.

Quand il fut à leur porte: Coucheriez-vous ici?

Vive l’amour! …

3 —Nenni, non non, mesdames! je vais à mon logis.

4 Quand il fut sur ces côtes, regarde derrièr’ lui.

5 A vu venir vingt hommes, ses plus grands ennemis.

6 —T’en souviens-tu, Eugène, un jour, dedans Paris,

7 Devant le roi, la reine, mon fils t’as démenti?

8 Arrête ici, Eugène, il faut payer ceci.

9 Tira son épée d’or, bravement se battit.

10 Il en tua quatorze, mais sans qu’il se lassît.

11 Quand ce vint au quinzième, son épée d’or rompit.

12 —Beau page, mon beau page, viens donc m’y secourir.

13 —Nenni, non non, beau prince, j’ai trop peur d’y mourir!

14 —Va-t’en dire à ma femme qu’ell’ prenn’ soin du petit.

15 Quand il sera en âge, il vengera ceci! [page 34]

Translation

1 O Prince Eugene was walking

In Paris town, one day,

Escorting three fair ladies

All hail to love!

Upon their homeward way.

Long live the fleur de lis!

2 Escorting three fair ladies

Upon their homeward way:

When they had reached their dwelling,

All hail to love!

They asked: “O will you stay?”

Long live the fleur de lis!

3 When they had reached their dwelling,

They asked, “O will you stay?”

“No, no! Nay, nay! fair ladies,

All hail to love!

Homeward I take my way.”

Long live the fleur de lis!

4 When he has climbed the hill-side,

Turning about, he sees

A score of men approaching,

All hail to love!

His greatest enemies.

Long live the fleur de lis!

5 “Do you recall, Prince Eugene,

One day, in Paris town,

Before the king and courtiers,

All hail to love!

You called my son a clown?”

Long live the fleur de lis!

6 “Be on your guard, Prince Eugene,

Your debt must now be paid!”

His hand has grasped the sword-hilt,

All hail to love!

And drawn the golden blade.

Long live the fleur de lis! [page 35]

7 He slew fourteen bold villains,

All with his mighty stroke.

But as he fought the fifteenth,

All hail to love!

His golden sword, it broke!

Long live the fleur de lis!

8 “Good page, O my good page-boy,

Do come and rescue me!”

“Nay, Prince, I dare not help you,

All hail to love!

For fear of death I flee …”

Long live the fleur de lis!

9 “Go hence and tell my Princess

To cherish well our son,

That he may wreak revenge

All hail to love!

When he’s to manhood grown!”

Long live the fleur de lis! [page 36]

LE RETOUR DU SOLDAT

1 Quand le soldat arrive en ville, (bis)

Bien mal chaussé, bien mal vêtu:

—Pauvre soldat, d’où reviens-tu?

2 S’en fut loger à une auberge:

—Hôtesse, avez-vous du vin blanc?

—Voyageur, a’-vous de l’argent?

3 —Pour de l’argent, je n’en ai guère;

J’engagerai mon vieux chapeau,

Ma ceinture, aussi mon manteau.

4 Quand le voyageur fut à table,

Il se mit à boire, à chanter,

L’hôtess’ ne fit plus que pleurer.

5 —Oh! qu’avez-vous, petite hôtesse?

Regrettez-vous votre vin blanc

Qu’un voyageur boit sans argent? [page 37]

6 —N’est pas mon vin que je regrette;

C’est la chanson que vous chantez:

Mon défunt mari la savait.

7 —J’ai un mari dans les voyages;

Voilà sept ans qu’il est parti.

Je crois bien que vous êtes lui.

8 —Ah! taisez-vous, méchante femme.

Je vous ai laissé deux enfants,

En voilà quatre ici présents!

9 —J’ai tant reçu de fausses lettres,

Que vous étiez mort, enterré.

Et moi, je me suis r’marié,

10 —Dedans Paris, y a grand guerre,

Grand guerre rempli’ de tourments.

Adieu, ma femme et mes enfants!

Translation

1 Home from the war the soldier has come, (bis)

His shoes are torn, his clothes out-worn.

“Tell me, soldier, whence do you come?”

2 Down to the inn he made his way:

“O hostess, a tankard of your wine!”

“Soldier, have you a silver coin?”

3 “I cannot pay with silver coin,

But keep this coat and hat of mine

To pay for your goodly wine.”

4 When at the table the soldier sat down

He drank his wine and sang a song,

But the hostess wept loud and long.

5 “What worries you, why do you weep?

Is it the wine that you regret,

Or that I shall be in your debt?” [page 38]

6 “’Tis not the cup of wine that you drank,

But ’tis the song you sang,” she said.

“My husband sang it, who now is dead.”

7 “My husband went to fight in the war,

He has been absent this many a year,

To him a likeness you do bear.”

8 “O keep your peace, you wicked woman!

When I went away, my children were two,

But now I see four here with you.”

9 “There came to me many false reports,

And told me that you had been slain.

I wept and wedded once again.”

10 “They wage a war down there in Paris,

A war that naught but blood can quell:

My wife and children, fare you well!” [page 39]

À LA CLAIRE FONTAINE

[sheet music]

1 A la claire fontaine, m’en allant promener,

J’ai trouvé l’eau si belle que je m’y suis baigné.

Depuis l’aurore du jour je l’attends,

Celle que j’aime, que mon cœur aime,

Depuis l’aurore du jour je l’attends,

Celle que mon cœur aime tant.

2 C’est au pied d’un grand chêne, je me suis fait sécher.

Sur la plus haute branche, le rossignol chantait.

Depuis l’aurore…

3 Chante, rossignol, chante, toi qui as le cœur gai.

Tu as le cœur à rire, moi je l’ai à pleurer.

4 J’ai perdu ma maîtresse sans l’avoir mérité.

Pour un bouquet de roses que je lui refusai. [page 40]

5 Je voudrais que la rose fût encore au rosier,

Et que le rosier même fût à la mer jeté.

6 Et que le rosier même fût à la mer jeté.

Je voudrais que la belle fût encore à m’aimer.

Depuis l’aurore du jour je l’attends,

Celle que j’aime, que mon cœeur aime.

Depuis l’aurore du jour je l’attends,

Celle que mon cœur aime tant.

Translation

1 In the crystal clear fountain, as I passed by one day,

I saw the limpid waters, and bathed in their spray.

Since the pale dawn I have longed for

The one I love, my heart’s belovèd.

Since the pale dawn I have longed for

The one that I fondly adore.

2 Beside a lofty oak-tree, in the cool wind I stray,

While from the top-most branch comes the nightingale’s sweet lay.

Since the pale dawn…

3 Nightingale, sing lightly, your heart is so gay,

Your heart is filled with laughter, mine with tears is grey.

4 For I have lost my dear love, lost her—ah! well-a-day!

All for a wreath of roses which I did gainsay.

5 And I would the rose blossoms were still on that tree,

Oh, I would that all the roses were swallowed by the sea.

6 Oh, I would the rose-blossoms were in the deepest sea.

I would that my belovèd had not forsaken me. [page 41]

LA ROSE BLANCHE

[sheet music]

1 Par un matin, je me suis levé; (bis)

plus matin que ma tante, eh là!

plus matin que ma tante.

2 Dans mon jardin je m’en suis allé (bis)

cueillier la rose blanche. (bis)

3 Je n’en eus pas sitôt cueilli trois

que mon amant y rentre.

4 —M’ami’, faites-moi un bouquet,

qu’il soit de roses blanches.

5 La belle en faisant ce bouquet,

ell’ s’est cassé la jambe.

6 Faut aller q’ri le médecin,

le médecin de Nantes.

7 —Beau médecin, joli médecin,

que dis-tu de ma jambe?

8 —Ta jambe, ell’ ne guérira pas

qu’ell’ n’soit dans l’eau baignante.

9 Dans un basin d’or et d’argent,

couvert de roses blanches. [page 42]

Translation

1 I rose early one summer morn, (bis)

While all were still asleep, hé là,

While all were still a-sleeping.

2 Down the garden I tripped along, (bis)

To pluck the snow-white rose, hé là,

To pluck the snow-white roses.

3 Three white buds I hardly plucked, (bis)

When my true-love I saw, hé là,

When my true-love came walking.

4 “Sweetheart, O make a nosegay white, (bis)

A nosegay fair and white, hé là,

A nosegay of white roses.”

5 While she made the nosegay white, (bis)

Her hand was pricked by thorns, hé là,

By thorns were pricked her fingers.

6 “You must fetch a doctor now, (bis)

To heal my bleeding hand, hé là,

To heal my bleeding fingers!”

7 “Doctor dear, O help me now, (bis)

And heal my wounded hand, hé là,

And heal my wounded fingers!”

8 “Not till you bathe it in water (bis)

Will your hand cease to bleed, hé là,

And all your bleeding fingers!

9 In a gold basin silver-wrought, (bis)

O bathe your hand at once, hé là,

And cover it with roses!” [page 43]

DANS LES HAUBANS

[sheet music]

1 J’ai fait faire un beau navire, un navire, un bâtiment.

L’équipag’ qui le gouverne sont des filles de quinze ans.

Sautons, légères bergères, dansons là légèrement!

2 L’équipage qui le gouverne sont des filles de quinze ans.

Moi qui suis garçon bon drille, j’me suis engagé dedans.

Sautons, légères bergères…

3 Moi qui suis garçon bon drille, j’me suis engagé dedans.

J’ai aperçu ma maîtresse qui dormait dans les haubans.

4 J’ai aperçu ma maîtresse qui dormait dans les haubans.

J’ai r’connu son blanc corsage, son visage souriant.

5 J’ai r’connu son blanc corsage, son visage souriant.

J’ai aperçu ses mains fines, ses cheveux dans un ruban.

6 J’ai aperçu ses mains fines, ses cheveux dans un ruban.

Suis monté dans les cordages, auprès d’elle, dans les haubans.

7 Suis monté dans les cordages, auprès d’elle, dans les haubans.

Lui ai parlé d’amourette; elle m’a dit: Sois mon amant! [page 44]

Translation

1 I have built a lovely sail-boat, O to sail upon the sea,

And a jolly crew I’ve chosen: maidens fair and fancy-free.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

2 Maidens fair of fifteen summers, what a jolly crew they make!

I’m the boatswain hale and hearty, whistling while the white-caps break.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

3 I’m the boatswain of the clipper, sailing through the stormy gales.

And I saw my darling sleeping up among the canvas sails.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

4 Up among the sails a-dreaming lay my darling all the while,

I knew her for her beauty and for her enchanting smile.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

5 I knew her dreaming beauty, her smile so sweet and fair,

Her white and slender fingers, and the ribbon in her hair.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

6 I saw her slender fingers, her hair in ribbons tied,

I climbed up on the rigging and I sat down by her side.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily!

7 I climbed up on the rigging, I sat down by her side.

I told her of my fancy. “Be my true-love,” she replied.

Come skip and dance with me,

Come and trip it merrily! [page 45]

LE MIRACLE DU NOUVEAU-NÉ

[sheet music]

1 Sont trois faucheurs dedans les prés; (bis)

Trois jeunes fill’ vont y faner.

Je suis jeune; j’entends les bois retentir;

Je suis jeune et jolie.

2 Trois jeunes fill’ vont y faner. (bis)

Celle qu’accouch’ d’un nouveau-né

Je suis jeune…

3 D’un mouchoir blanc l’a env’loppé;

4 Dans la rivière ell’ l’a jeté.

5 L’enfant s’est mis à lui parler.

6 —Ma bonne mèr’, là vous péchez.

7 —Mais, mon enfant, qui te l’a dit?

8 —Ce sont trois ang’s du paradis.

9 L’un est tout blanc et l’autre gris;

10 L’autre ressemble à Jésus-Christ. [page 46]

11 —Ah! revenez, mon cher enfant.

12 —Ma chère mère, il n’est plus temps.

13 Mon petit corps s’en va calant;

14 Mon petit cœur s’en va mourrant;

15 Ma petite âme, au paradis.

Translation

1 There are three mowers in the field,

There are three mowers in the field,

Three maidens there the hay-fork wield.

Oh, I’m young and hear the wild melody,

I am young and free.

2 Three maidens wield the hay-fork there, (bis)

And one a little child did bear.

Oh, I’m young…

3 And one did bear a little child. (bis)

She wrapped it in a kerchief white.

4 In a white kerchief it was sewn (bis)

And then into the river thrown.

5 When it was flung into the deep, (bis)

The little one began to weep.

6 Weeping still the infant cried, (bis)

“My mother, now a sin you hide.

7 You hide a sin, my mother dear.” (bis)

“My little child, how did you hear?

8 Who made you speak so wonder-wise?” (bis)

“Three angels out of Paradise,

9 Three angels who in Heaven pray, (bis)

One was white and one was grey. [page 47]

10 One was grey and one was white, (bis)

One appeared like Jesus Christ.

11 One like the Christ was meek and mild.” (bis)

“Come back to me, my little child!

12 My little child, I cannot wait.” (bis)

“Oh, mother dear, it is too late!

13 It is too late, my mother dear, (bis)

My little arms now disappear.

14 Now my little arms have dropped, (bis)

Now my little heart has stopped.

15 My little voice no longer cries, (bis)

For my soul is in Paradise.”

Oh, I’m young and hear the wild melody,

I am young and free. [page 48]

ROSSIGNOLET SAUVAGE

[sheet music]

1 Rossignolet sauvage, le roi des amoureux,

Voudrais-tu bien me porter une lettre

A Isabeau, celle que mon cœur aime?

2 —Celle que ton cœur aime, je ne la connais pas.

—Tu voleras de bocage en bocage;

Tu trouveras ma bergère à l’ombrage.

3 —Bonjour, bonjour, la belle, le bonjour est pour toi!

Chère Isabeau, votre amant est en peine.

Aimez-le donc tout autant qu’il vous aime.

4 —L’aimer autant qu’il m’aime, non non, je ne veux pas!

De trop aimer, ce n’est point là l’usage;

De l’épouser je n’ai pas l’avantage.

5 —Les garçons sont fidèles, les fill’s ne le sont pas:

Ell’s viv’nt toujours dans la même espérance

De s’en aller dans la ville de France.

6 —Dans la ville de France, non non, je n’irai pas!

Je n’y ai pas de parrain ni marraine

Pour y conter mes chagrins et mes peines.

7 —Du chagrin, de la peine, non, tu n’en auras pas;

Mais promets-moi la foi du mariage.

Ça ira bien dans ton petit ménage. [page 49]

Translation

1 “Nightingale singing wildly, Sov’reign of love’s sweet land, Now do my bidding: Carry this letter swiftly To Isabel’s hand, To her I love dearly.” 2 “She whom you love so dearly Is to me quite unknown.” “Wing your way lightly From meadow to green meadow. There you’ll find dreaming My darling in the shadow.” 3 “Greetings to you, fair lady! Greetings to you I bring, To you Isabel, Whose true-love is a-pining For want of your love, Who should love him so well.” 4 “My love is given wisely And nevermore too well, Lest too much loving Should some day cause me grieving. I’ll remain so free Till my true love marry me.” 5 Young men are full of longing, Young maids are full of pride, Love words are sweet, But my true love must come And promise me To take me for his loving bride. [page 50]

QUI N’A PAS D’AMOUR

[sheet music]

1 La belle Lisette Chantait l’autre jour, Chantait l’autre jour. Les échos répètent: Qui n’a pas d’amour, Qui n’a pas d’amour, N’a pas de beaux jours. 2 Son berger l’appelle Le berger Colin, Le berger Colin. Veill’nt à la chandelle, La main dans la main, Du soir au matin. [page 51] 3 —Si gente, si belle, Dedans tes atours, Dedans tes atours, O ma tourterelle! Répétons toujours Répétons toujours Nos serments d’amour. 4 Unissons ensemble Ton cœur et le mien; Ton cœur et le mien. —Ne puis m’en défendre. O berger charmant, O berger charmant, A toi je me rends!

Translation

1 It was the pretty Lisette, Singing an old air; It was the pretty Lisette, Singing an old air, Singing an old air! The echo kept repeating; Whose love is not fair, Whose love is not fair, His days are so bare! 2 A jolly shepherd loved her, Colin was his name; A jolly shepherd loved her, Colin was his name, O Colin was his name! Her hand in his he wooed her, All through the starry night, Until the dawn came, Through the starry night. [page 52] 3 So gentle and so pretty In your dainty gown, So gentle and so pretty, In your dainty gown, O in your dainty gown! O my sweet and little dove, Let us keep repeating Our vows of sweet love, Let us keep repeating! 4 Let us unite together Your dear heart and mine! Let us unite together Your dear heart and mine! O your dear heart and mine! I shall hear your pleading Charming shepherd-boy, My love is all thine! Charming shepherd-boy. [page 53]

LÀ-HAUT SUR CES MONTAGNES

[sheet music]

1 Là-haut sur ces montagnes, j’ai entendu pleurer. Oh! c’est la voix de ma maîtresse; il faut aller la consoler. (bis) 2 —Qu’avez-vous donc, bergère, qu’a’-vous à tant pleurer? —Ah! si je pleur’, c’est de tendresse; c’est de vous avoir trop aimé. 3 —De tant s’aimer, la belle, qui nous empêchera? Faudrait avoir un cœur de pierre à qui ne nous aimerait pas. 4 —Les moutons dans ces plaines sont en danger des loups… —Pas plus que vous, belle bergère, vous qui ête’ en danger d’amour. 5 —Les agneaux vive’ à l’herbe, les papillons aux fleurs. Et toi et moi, jolie bergère, pourquoi n’y vivre qu’en langueur? [page 54]

Translation

1 Out there among the mountains I heard a maid weeping. Oh, ’tis the voice of my belovèd, I must comfort her with my pleading. ’Tis the voice of my belovèd, I must comfort her with my pleas. 2 “What saddens you, belovèd? Why do you shed these tears?” “Ah, if I weep, it is through loving, Loving you despite all my fears.” 3 “Such love as ours, my darling, No one can e’er gainsay; His heart would be made of granite Whose affections you could not sway.” 4 “The sheep out in the meadows Are frightened by the wolf.” “No more than you, my shepherdess, Are haunted by the fear of love.” 5 “The lambs skip through the grasses, The butterfly here sways, Oh, would that we, my shepherdess, Could thus beguile the fleeting days!” [page 55]

DAME LOMBARDE

First version, sung by Mme. Zephirin Dorion, an Acadian of Port Daniel, Chaleur bay:

[sheet music]

Second version, sung by Joseph Ouellet, la Tourelle, Gaspe:

[sheet music]

Third version, sung by François Miville, la Tourelle, Gaspe:

[sheet music]

[page 56]

Fourth version, sung by Ovide Souci, Temiscouata:

[sheet music]

Fifth version, sung by Mme. Magloire Savard, Ruisseau-aux-Patates, Gaspe:

[sheet music]

Sixth version, sung by Mme. Jean-Baptiste Leblond, Sainte-Famille, island of Orleans:

[sheet music]

[page 57]

Seventh version, sung by Mme. Aimé Simard, Saint-Irénée, Charlevoix:

[sheet music]

1 Chère voisine, enseignez-moi, mais enseignez-moi donc,

mais enseignez-moi donc;

Enseignez-moi de la poison: c’est pour empoisonner,

c’est pour empoisonner,

2 Pour empoisonner mon mari, qui est jaloux de moi.

—Allez là-bas sur ces coteaux, là vous en trouverez.

3 La tête d’un serpent maudit, là vous la couperez.

Entre deux plats d’or et d’argent, mais vous la pilerez.

4 Dans un’ chopine de vin blanc, vous en mettrez.

Quand votre mari viendra des bois, grand soif il aura.

5 Il vous dira: Belle Isabeau, apporte-moi de l’eau.

Répondez: Ce n’est pas de l’eau, c’est du vin qu’il vous faut!

6 A mesur’ que la bell’ versait, le vin noircissait.

L’enfant qu’était dans le berceau, son père il avertissait:

7 —Papa, papa, n’en buvez pas! Ça vous ferait mourrir.

Il lui a dit: Belle Isabeau, t’en boiras devant moi!

—Non, non, dit-elle, mon cher mari, je n’ai point de soif.

8 —La mort devrait-elle y passer, la belle, vous en boirez!

—Ah! que maudit soit ma voisine de m’avoir enseigné! [page 58]

Translation

1 “O Gossip dear, please, teach me how,

O please, teach me how,

Please, teach me how to brew a drink,

O please teach me how to brew a deadly drink.”

2 “A deadly drink you must distil,

Your husband to kill,

Who tortures you with jealousy.

And yonder you must climb upon the steepest hill.

3 There you will find an evil snake,

Now cut off its head.

Between two gold and silver plates

You must crush the snake until it is quite dead.

4 And in a pint of white sweet wine

You must place it first,

And when your husband home returns,

Home from the woods, then very great will be his thirst.

5 And he will say, ‘Sweet Isabel,

Some cold water, please!’

Then you will say, ‘Not water cold,

Dear husband, let this sweet wine your thirst appease’.”

6 And while she poured for him the wine,

O so black it turned,

The babe that in the cradle lay

He spoke up suddenly and his dear father warned.

7 “O father, father, do not drink!

It will make you die.”

“Sweet Isabel, you drink this first.”

“No, no,” she said, “dear husband, no! No thirst have I.”

8 “If death should come, my pretty sweet,

You will drink this first.”

“My neighbour who has taught me this,

O now I pray that she may be forever cursed!” [page 59]

RENAUD

[sheet music]

1 La mère étant sur les carreaux

A vu venir son fils Renaud:

—Mon fils Renaud, mon fils chéri,

Ta femme est accouhé’ d’un fils.

2 —Ni de ma femm’, ni de mon fils

Je n’ai le cœur réjoui.

Je tiens mes trip’s et mes boyaux

Par devant moi, dans mon manteau.

3 Ma bonne mère, entrez devant

Faites-moi faire un beau lit blanc.

Qu’il soit bien fait de point en point,

Et que ma femm’ n’en sache rien.

4 Mais quand ce vint sur la minuit,

Le beau Renaud rendit l’esprit.

Les servant’s s’en vont pleurant,

Et lest valets en soupirant. [page 60]

5 —Ah! dites-moi, ma mère ô grand,

Qu’ont les servan’t à pleurer tant?

—C’est la vaissell’ qu’ell’s ont lavé’,

Un beau plat d’or ont égaré.

6 —Pour un plat d’or qu’est égaré,

A quoi sert-il de tant pleurer?

Quand Renaud de guerr’ viendra

Un beau plat d’or rapportera.

7 —Ah! dites-moi, ma mère ô grand!

Qu’ont les valets à soupirer?

—C’est leurs chevaux qu’ils ont baignés;

Un beau cheval ils on noyé.

8 —Pour un cheval qu’ils ont noyé,

Ma mère, faut-il tant soupirer?

Quand Renaud de guerr’ viendra,

Un beau cheval ramènera.

9 Quand le matin fut arrivé,

La bière il a fallu clouer.

10 —Ah! dites-moi, mère m’amie

Ce que j’entends cogner ainsi?

—C’est le petit dauphin qu’est né;

La tapisserie leur faut clouer.

11 Le dimanche étant arrivé,

A l’église il lui faut aller.

Le rouge elle devait porter,

Mais le noir lui fut présenté.

12 —Ah! dites-moi, mère m’amie,

Pourquoi changez-vous mes habits?

—A toute femm’ qu’élève enfant

Le noir est toujours plus séant. [page 61]

13 En passant par le grand chemin

Ont fait rencontr’ de pélerins:

—Vrai Dieu, voilà de beaux habits

Pour une femme sans mari.

14 —Ah! dites-moi, mère m’amie,

Ce que les p’tits passants ont dit?

—Ma fill’, les passant ont dit

Que vous aviez de beaux habits.

15 A l’église est arrivé’;

Un cierge lui ont présenté.

—Sont les cloch’s que j’entends sonner;

Le coup de mort ell’s ont donné.

16 Ma mèr’, voici un tombeau,

Jamais n’en ai vu de si beau.

—Ma fill’, ne pouis vous le cacher,

Le beau Renaud a trépassé.

17 Vrai Dieu, puisque c’est mon mari,

Je veux m’en aller avec lui.

Ma mèr’, retournez au château,

Prenez soin du petit nouveau.

Translation

1 A mother standing at the door

Saw her son coming from afar.

“O welcome home, my dearest John

Your wife has borne a little son.”

2 “Nor for my wife, nor for my child

My heart is filled with joyous pride.

My words are stifled in my throat,

My wounds are hidden in my coat.”

3 “Go, mother dear, now take a sheet,

Prepare my bed all white and neat.

All neat and white my bed must be,

Only my wife must not see me.” [page 62]

4 When midnight came with dreary toll,

The gallant John gave up his soul.

The servants all began to weep,

The neighbours wakened from their sleep.

5 “O mother dear, now tell me why

The servants all so loudly cry?”

“All for a platter which they lost,

A platter that much gold has cost.”

6 “For golden plates tears are not shed;

Tell them to dry their tears instead.

When my dear john comes from afar,

Our golden plate he shall restore.”

7 “O mother dear, now tell me why

The hostlers all so sadly sigh?”

“Their horses by the lake they groomed

When suddenly a mare was drowned.”

8 “All for a mare that drowned so deep,

O mother, must the hostlers weep?

When my dear John comes from afar,

He shall bring them a goodly mare.”

9 O when the dawn had risen clear,

They drove the nails into the bier.

10 “Now mother dear, O tell me, pray,

Why do they drive in nails to-day?”

“Because you bore a little heir,

Tapestries clothe these walls so bare.”

11 When Sunday came, they ready made

To join the joyful church parade.

She donned a robe of crimson red,

But they gave her black garb instead. [page 63]

12 “O mother dear, now tell me true,

Why is my gown of darkest hue?”

“White is the gown of the young bride,

But dark for her, who bore a child.”

13 As they were walking on their way,

They heard some passing pilgrims say:

“Tis meet a widow should wear gown

Of mourning hue for her lost one.”

14 “O dearest mother, tell me, pray,

What do the passing pilgrims say?”

“My child, the pilgrims say that you

Are dight in garb of fitting hue.”

15 Within the church at last she stands,

A lighted taper in her hands.

“I hear the bells with mournfull toll,

They ring for a departed soul.”

16 “I see a tomb, O mother dear,

More beautiful than any here.”